Sunday, Sept. 6, 2020 | 2 a.m.

Paul Velez, a lieutenant with University Police Services at UNLV, received a phone call saying there was a security issue at the university’s International Gaming Institute that required his attention.

Velez was wearing street clothes while working undercover and initially thought one of his colleagues would be better fit for the assignment. But he hustled over to the building on the north side of campus by Swenson Avenue and Flamingo Road to meet Bo Bernhard, the institute’s executive director.

“Bo starts explaining, ‘We are having this meeting. Nobody can know about it,’ ” Velez said. “He swears me to secrecy. He tells me to secure the building and not let anyone in. I’m like, ‘Wait, who is in this meeting?’

“He says, ‘Mark Davis of the Raiders. They are looking at moving to Las Vegas,’” Velez continued.

“At this point, nobody can know. I’m blown away. I’m a diehard Raiders fan. Then everyone starts coming into the room, Mark Davis and all of the Raiders’ brass. I couldn’t believe I was there.”

That February 2015 meeting, where Bernhard detailed the institutes’s research on the integrity of sport betting, problem gambling and local crime trends — those perceived pitfalls that had led the NFL to keep its distance from Las Vegas — got the ball rolling on the Raiders relocating from Oakland to Las Vegas.

The Las Vegas Raiders begin their maiden season next Sunday against the Carolina Panthers in Charlotte, N.C.

“I’m a kid who grew up in Vegas. I was very aware of the league’s perception of us: They didn’t like us,” said Bernhard, who is widely considered one of the world’s authorities on gaming research.

Keeping the meeting secret was such a priority that Raiders leadership didn’t even put it on their calendars. If word got out that they were seriously flirting with relocating to Las Vegas, it could have jeopardized the talks.

The NFL didn’t have the information at Bernhard’s disposal that showed how Nevada was a leader in regulating sports wagering, and even if the league did, the league likely would have still passed because of its archaic view of a city built on gaming.

Davis had a view of the Strip skyline from his seat in the boardroom for that fateful meeting. Davis could look out and see the many resorts — which are so much more than casinos with their world class entertainment, food and shopping — that have transformed a stretch of Las Vegas Boulevard into one of the world’s most recognizable pieces of real estate.

By the time the meeting concluded, Davis was convinced world-class professional sports would soon be added to the list of what Las Vegas is known for. The Raiders would be exploring a move.

“Mark in the end goes, ‘Can you put that in a big academic report with a UNLV stamp on it?,’” Bernhard said.

Yearning for big-time pro sports

In 2003, the Montreal Expos were purchased by Major League Baseball and entertaining offers to relocate. Las Vegas was one of about five cities under consideration. But instead of becoming Las Vegas’ first major-league professional team, the Expos moved to Washington, D.C., and became the Nationals.

A few years later, then-Las Vegas Mayor Oscar Goodman started pursuing an NBA franchise to relocate to downtown. When those plans fizzled, another proposal picked up steam with a group attempting to bring Major League Soccer to Las Vegas.

There were significant problems with all of the pitches: There was no arena or stadium in Las Vegas to host a franchise, and there was no public appetite for taxpayer dollars to construct a facility.

There were a few attempts at developing a stadium or arena. But those never gained much traction — mostly because there was no guarantee of a franchise to be a tenant.

Often, Las Vegas was simply a decoy for an existing franchise to get a better building in their current city. As recently as 2018, Phoenix Suns owner Robert Sarver threatened to move the franchise here if demands for publicly funded renovations to Talking Stick Resort Arena weren’t approved by the city. They eventually were.

“We were used as a stalking horse a lot,” said Gov. Steve Sisolak, who previously served on the Clark County Commission and was part of many of the early meetings with Raiders’ leadership.

Since the start of the 2014 season, the Raiders were the only NFL team sharing a stadium with a baseball franchise. That meant home games where players had to brace for impact when tackled on the Oakland A’s infield at the aging Oakland Coliseum. Davis had repeatedly tried to get a new stadium in Oakland, and he repeatedly was met with resistance.

When the interest in Las Vegas became known, a common assumption was that Davis was attempting to put pressure on Northern California officials to help the Raiders get into a new stadium.

But in Las Vegas, leaders sensed something different, mostly because Davis was so sincere in his desire for the Raiders to be here.

“My original thought, frankly, was they would work something out in Oakland,” said Steve Hill, the chief executive officer of the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, and the chair of the Las Vegas Stadium Authority. “Uprooting a team isn’t easy to do. It doesn’t happen often.

“But when you meet Mark, he is that sincere. He sincerely wanted to move to Las Vegas. Whether that would work or not, it was too early to tell.”

Planning a stadium

In April 2016, a few months after the Raiders went public with their intentions to explore options in Las Vegas, Davis visited UNLV’s Sam Boyd Stadium as part of a tour with officials. The Raiders, in the many moving parts of plotting their move, may have needed to use Sam Boyd as a stopgap until a new stadium was constructed.

Sam Boyd, a 20-minute drive east on Tropicana Avenue from campus, is a decent college venue, especially for a mid-major conference program like UNLV. But it lacked the modern amenities — updated locker rooms, training facilities and paved parking lots — for perennial loser UNLV to take the next step. Even worse, it was located in a remote part of town, and students rarely attended games.

UNLV, like the Raiders in Oakland, was determined to get a better home venue.

A photo circulated of Davis alongside then-UNLV President Len Jessup, athletic director Tina Kunzer-Murphy, football coach Tony Sanchez and adviser Don Snyder, who previously worked with Majestic Realty Co., the California-based developer working with UNLV to find a location and funding for the stadium.

After years of trying to leave Sam Boyd, this plan had legs. Program supporters were ecstatic.

“Everything was very preliminary at that time, of course,” Jessup said. “But I could tell (Davis) was very genuine. His interest seemed genuine. You got the feeling that this would actually work.”

The plan, at least initially, was to erect the stadium on a 42-acre lot that UNLV had purchased for $50 million at Tropicana and Koval Lane. The private-public partnership had the backing of the Las Vegas Sands Corp., whose owner Sheldon Adelson would provide financial backing for the proposed 65,000-seat facility.

The desire to develop a stadium and expand the Las Vegas Convention Center was briefly mentioned during the 2015 Nevada legislative session but no action was taken. Instead, in June 2015, Gov. Brian Sandoval formed the 11-member Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee. One of the committee’s purposes was to study building a stadium in Las Vegas for concerts, festivals, sporting events like soccer exhibitions and college bowl games, and more. The other was to look at expanding the convention center

And now, as fate would have it, the Raiders and Adelson, whose net worth is $31 billion, were on board for the stadium.

“The first major obstacle was how to get both projects done in what most in the resort corridor would feel was a reasonable (tax increase),” Hill said. “That took time to overcome.”

Bringing the NFL on board

Before the Raiders could ask NFL owners to vote on relocation, Nevada had to do its part.

The public-private partnership envisioned in financing the new stadium had three legs: the state would increase hotel room taxes in Las Vegas and the surrounding area to cover the public’s $750 million portion of the project; Adelson would contribute up to $650 million; and the Raiders would cover the remaining $500 million for the $1.9 billion proposal. The stadium would be constructed on 62 acres near Russell Road and Interstate 15. The land on Tropicana was ruled out because an airline carrier complained the structure would disrupt flight patterns in and out of nearby McCarran International Airport.

A special session of the Nevada Legislature was called in October 2016 to consider the tax increase. Needing two-thirds majority of lawmakers to sign off, even if it met securing one of 32 NFL franchises, wouldn’t be an easy task. The $750 million state contribution, after all, could be used for other Nevada needs, such as the severely underfunded education system.

Having UNLV as one of the benefactors surely helped. The stadium would do more than just help UNLV’s football program win games, leaders explained. It was part of a bigger plan to move UNLV athletics to a Power 5 Conference, such as the Pac-12 or Big 12, which would generate millions in annual revenue to transform other university programs.

“UNLV was critical to the deal happening,” Jessup said. “Decision-makers at the legislative level could accept going to great lengths to steer tax dollars from the Strip for the project knowing there was some public good. Same thing on the Strip; they were OK increasing room tax if there was some public benefit.”

On the day the Nevada Assembly voted, Democratic Assemblyman Richard Carrillo gave an impassioned speech about how the construction jobs created by the tax increase — it would also fund the Las Vegas Convention Center’s $980 million expansion — would stabilize an industry still reeling from the recession from over a decade ago.

“When we hit that button green or red, we’re changing lives,” Carrillo said.

The bill passed 28-13 in the Assembly, meaning if one less lawmaker hit the button green, the Raiders could be representing a different city come next Sunday. In total, the state approved $1.17 billion for both projects in the form of municipal bonds from Clark County backed by the tax increase.

The next step was to get the NFL on board, starting with the fall meeting of NFL owners a few days after the Nevada vote. While nothing was guaranteed, the pairing of stadium funding and interested professional team was finally in place.

“If the NFL was not seriously considering doing this, they would have let us know something. ‘Hey you guys need to stop this effort,’” Hill said.

Dispelling myths

Dallas Cowboys quarterback Tony Romo was scheduled to speak at a fantasy football seminar on the Strip in the summer of 2015 until the league stepped in and forbade it. Fantasy football is a form of gambling and the league’s integrity could be jeopardized, the league reasoned.

Two years earlier, in 2013, ESPN reported the league wouldn’t consider an exhibition game being played in Las Vegas because wagers would be placed on the game. The American Gaming Association in 2018 said $95 billion was wagered illegally on college and pro football, which is partially why the league is so popular.

Here, of course, wagering on sporting events is heavily regulated, although Bernhard doubted the league realized to what extreme levels.

“Here’s what the NFL isn’t aware of,” Bernhard said in a presentation to 30 casino executives in 2015.

Not so ironically, it was that meeting that started the process of the Raiders’ relocation.

One of the attendees — the last person to register, as fate would have it — was former Raider Napoleon McCallum, who worked for the Las Vegas Sands Corp. and had long tried to get Davis to consider bringing the franchise to Las Vegas.

But with gambling in the way, how?

During a break, McCallum approached, “Do you want to meet Mark Davis? I think I just heard all the answers?,” Bernhard recalled him saying. A few weeks later, Davis was in town for the meeting.

The league would have many doubts, all of which Bernhard and other scholars had data to refute. The claims were nothing more than stereotypes: Aside from dispelling myths about sports betting, the research team also addressed concerns about crime on the Strip and the sense Las Vegas didn’t have that community feel.

Jessup said Bernhard’s presentation to the NFL was vital because “a lot of people had to be convinced.”

But Bernhard doesn’t want any credit, saying, “We kicked some things off. Some powerful people ran it over the goal line.”

The goal line was cleared March 27, 2017, with a 31-1 vote during an owners meeting in Phoenix, where Bernhard was part of the contingent representing the team.

Hurdles for the new stadium

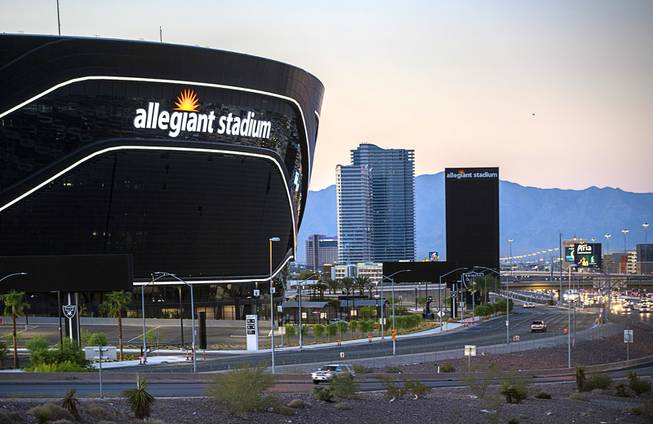

Getting approval from the state and league, while the most important and difficult steps, was only half of the battle. Over four years, many obstacles could have derailed the project, including in 2017 when Adelson pulled his financing for the domed venue, later named Allegiant Stadium after the local airline secured rights in an undisclosed deal.

Adelson’s timing wasn’t ideal — two months before the NFL was supposed to approve the move.

“They want so much,” Adelson told Reuters days before backing out. “So I told my people, ‘Tell them I could live with the deal, I could live without the deal. Here’s the way it’s gonna go down. If they don’t want it, bye-bye.’”

But the Raiders, three weeks before the NFL vote, secured a $650 million loan from Bank of America to cover Adelson’s portion. The project was saved.

Yet, there were more, unexpected, roadblocks.

With a scheduled completion date of July 2020, and the Raiders moved out of Oakland at the end of the 2019 season, there was little room for hiccups in the construction process.

Then, the coronavirus pandemic hit the United States in mid-March. Sisolak temporarily shuttered all nonessential business in Nevada, but construction crews kept working at the stadium with no interruption.

More than a dozen workers would test positive for the coronavirus to temporarily close affected areas for cleaning. Despite rising temperatures as spring progressed, workers had to wear face coverings to help lessen the spread of the virus. As social distancing became the norm, some stadium construction workers transitioned to evening shifts to reduce the number of people on site during the day, which could reach 2,000.

The work continued, even as some other big projects, such as the MSG Sphere entertainment complex on the Strip, were forced to table operations.

“When you look back at what this team has been through and what they’ve endured, it’s pretty amazing,” Eric Grenz, vice president of operations for the joint build team of Mortenson and McCarthy, told the Sun in July. “I think most companies probably would have thrown in the towel a long time ago.”

Working through hard times with the home teams

One of the most meaningful days in sports for Las Vegas happened Oct. 10, 2017, at T-Mobile Arena. It was the first-ever regular season home game of Vegas Golden Knights, the area’s first professional sports team. And, unfortunately, it happened days after a mass shooting claimed 59 lives on the Strip.

An emotional pregame tribute included recorded messages from the likes of Keith Urban and Las Vegas-based rockers Imagine Dragons, followed by each Golden Knights player walking onto the ice with a first responder who had helped save lives during the aftermath of the mass shooting. Many of the 18,000 fans filling T-Mobile to its capacity joined in singing the “Star-Spangled Banner” before Deryk Engelland — a longtime Las Vegas resident — spoke to the crowd.

“Now, we will do everything we can to help you and our city heal. We are Vegas Strong,” he said.

The Golden Knights went on to score three goals in the opening five minutes of the game, and instantly became the town’s favorite team.

“We grabbed onto something to believe,” said Sisolak from his Las Vegas office, which is a mini-shrine to the area’s sports team complete with a framed Golden Knights jersey and bobbleheads, and a Raiders construction site hard hat.

“They showed that we are going to work our way through this.”

The Raiders, some four years after first exploring and then making a move to Las Vegas, can have a similar impact.

Nevada has been hit hard by the pandemic with record unemployment, currently at 16%, and some casinos still shuttered. The launch of a new major-league team in Las Vegas couldn’t have come at a better time, even if fans won’t be allowed in the stadium this season.

It is a credit to the Raiders for following through on their vision to relocate to Las Vegas, Sisolak said.

“There were some potholes in the road, but nothing broke the axle off the car,” Sisolak said of the process. “Nothing stopped them. They knew what they wanted. They made believers out of nonbelievers.”

The Raiders are making Las Vegas an NFL city. It begins Sunday at Carolina.

Ray Brewer can be reached at 702-990-2662 or [email protected]. Follow Ray on Twitter at twitter.com/raybrewer21