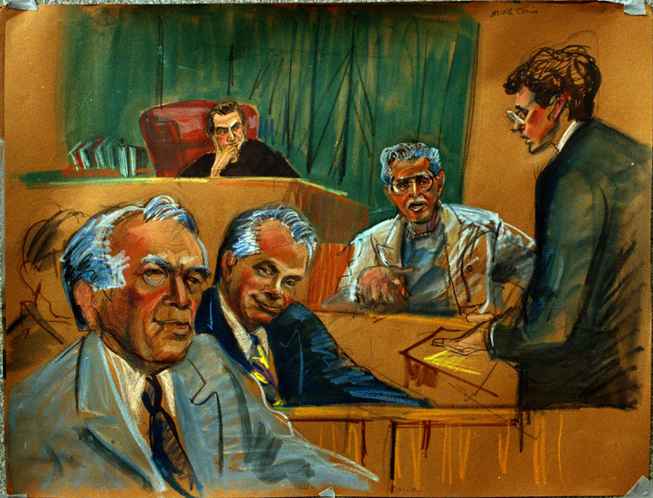

Marilyn Church / AP File (1992)

John Gotti, second from left in this sketch, appears March 21, 1992, in U.S. District Court. From left are: actor Anthony Quinn, Gotti, U.S. District Judge I. Leo Glasser; witness Anthony Gurino and assistant U.S. attorney John Gleeson. Tonight at the Mob Museum, Gleeson will speak about how federal authorities finally were able to bring Gotti, the “Teflon Don,” to justice.

Wednesday, May 24, 2023 | 2 a.m.

On a November evening in 1991, John Gleeson received a late-night phone call that would reshape not only his upcoming trial but also, as many have said, the power structure of the Mafia in America.

It had been five years since Gleeson lost his first case against John Gotti, who rose to celebrity status and was dubbed “The Teflon Don” by media because charges failed to stick against the Gambino family crime boss.

Overall, Gleeson worked for about a decade investigating and prosecuting the New York crime family as a former assistant United States attorney for the Eastern District of New York. Gleeson will talk about the historic John Gotti case and sign his book “The Gotti Wars” during an event tonight at The Mob Museum.

The focus of prosecutors and the FBI was to charge anyone connected to the family in hopes they’d flip on Gotti, following trials that didn’t result in his conviction, Gleeson said.

On that November night someone flipped, and not just anyone.

Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, the Gambino underboss, was talking.

“We pulled him out of a detention center at midnight,” Gleeson said in an interview Friday. “We had indicted him for three murders, and he’s telling me about 16 other murders he’s committed. It takes awhile for someone to tell you about 16 murders.”

There were breaks as the discussion rolled into the early morning hours, Gleeson said.

During one of the breaks, Gravano threw out, “‘By the way, I fixed that seven-month trial you lost a few years ago,’ ” Gleeson says.

Gleeson says Gravano then added that one of the jury members had been paid off.

While today, it is well known that the early Gotti trial was fixed, Gleeson said he hadn’t known prior to that November 1991 meeting with Gravano.

Gotti took over the Gambino family syndicate soon after ordering the successful murder of crime boss Paul Castellano in 1985.

In 1986 a jury acquitted Gotti in a racketeering case, and in 1987 a jury acquitted him of loan sharking, illegal gambling, murder and armed hijacking charges.

As a federal prosecutor, Gleeson worked closely with the FBI during the investigation of Gotti and the crime family. It became obvious that to convict Gotti, they needed him talking about his illegal behavior on tape.

“We wanted to get a recording device where he was talking about crimes,” Gleeson said. “It took us years, but we eventually got a bug in the apartment at the Ravenite Social Club.”

Gotti was known to hold regular meetings with the crime family at Ravenite.

The bug eventually gave prosecutors enough evidence to charge Gotti with new racketeering offenses; five murders, including Castellano’s; conspiracy to murder; loan sharking; illegal gambling; obstruction of justice; bribery; and tax evasion.

The tapes also connected the American Mafia to labor unions — from which, at the time, the crime organization derived a lot of its wealth and power, Gleeson said.

It was 10 weeks prior to the trial when Gleeson sat with Gravano for the early-morning meeting.

“It completely changed the case,” Gleeson said. “It went from the tapes to Gravano testifying.”

Gleeson also became concerned about the anonymous jury, after a member of the anonymous jury from the first trial was paid off.

“The jury member had lied his way into the case and then reached out to Gotti and sold his vote,” Gleeson said.

It was decided the jury would be sequestered and they were under constant surveillance by U.S. Marshals, with even their phone calls listened to, Gleeson said.

“There was no way for them to reach out because the U.S. Marshals would know,” Gleeson said.

Asked if he was ever in fear for his own life, Gleeson said no. He said there had been a contract out for his life and he had a bodyguard, but it would have caused the mob family more trouble if they’d retaliated against him.

Within an hour of the cross-examination of Gravano on the stand, everyone in the courtroom knew Gotti would be convicted, Gleeson said.

“He was the best accomplice witness anyone had seen in that courthouse, and there was no way that the jury was not going to convict,” Gleeson said “He spoke in the present tense, as if he was still the underboss. We rested as quickly as we could.”

Gravano flipping did more than just assure the conviction of Gotti, Gleeson said.

Prior to Gravano flipping, there was always an assumption that there was something wrong with the person who flipped. They were just weak and everyone assumed they would, he said.

“Gravano was the underboss,” Gleeson said. “He was very well respected among gangsters.”

When Gravano flipped, the word on the street wasn’t that there was something wrong with Gravano but with the mob, Gleeson said.

“After he flipped we couldn’t stop the flow of people coming through the door,” Gleeson said.

The Gotti conviction and the fallout from it, Gleeson said, caused the mafia to lose its hold on the labor unions.

“The mob was the mob because of its grip on all the unions,” Gleeson said. “A lot of people have a misconception that it is about gambling and loan sharking and those things, but the mob was siphoning off millions of dollars a year by holding the unions. When Gravano flipped, it broke the mob’s grip on all the unions. There’s no money in it anymore.”

The Mob Museum event, “Taking Down Gotti: The Prosecutor Who Put The Teflon Don Away,” will start at 7 p.m. with a book signing at 8 p.m. today at 300 Stewart Ave. The coast of the event is museum admission and is free to museum members.