Tuesday, April 22, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- Protector of the wash (12-04-2006)

- Progress, nature at odds in land fight (3-30-2006)

The Las Vegas buckwheat seems like a small, unassuming plant.

But if conservationists get their way, this little flowering shrub could halt development of some of the last remaining open space in the Las Vegas Valley.

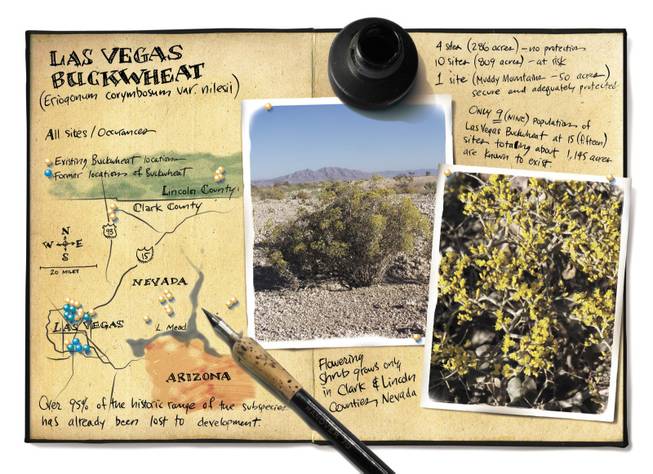

Although the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has said the plant deserves government protection, the buckwheat is at the end of a long line of other species that officials say are more deserving. Because the threats to the buckwheat, which grows only in parts of Clark and Lincoln counties, aren’t imminent, the feds have said its designation can wait.

Rob Mrowka, the local conservation advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity, a national group that recently opened an office in Las Vegas, disagrees. His group plans to announce today that it will petition the federal government to speed up the process.

If the feds list the buckwheat as an endangered species, it will stop homes or parks from being built in several areas in the valley where it now grows, including on federal land set to be sold under the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act.

It would become the latest species to become caught up in the fight over what little open space is left in the valley. While homebuilders and city officials think land should be available for development, conservationists are asking whether it might be time to stop expanding and start protecting natural resources such as the buckwheat.

“Do we want to give up public lands for development and sacrifice this rare plant that’s not found anywhere else in the world, or do we want to value what’s unique to Las Vegas and set aside those areas and protect them?” Mrowka said.

Scientists didn’t determine the Las Vegas buckwheat was its own species of shrub until 2004, Mrowka said. And if it continues to be destroyed in Clark County at its current rate, it will soon disappear from Earth altogether, experts say.

In 2004, the plant held up the sale of public land to developer Olympia Group. In the end the company was forced to set aside a 300-acre conservation area, including 59 acres of buckwheat, of the 2,675 acres it had purchased for $639 million. But 92 acres of buckwheat outside the conservation area were destroyed.

Champions of development point to the deal as just another case of a single, pesky species holding up progress in Las Vegas.

Mrowka, on the other hand, sees it as another step toward extinction of the buckwheat.

The Nevada Natural Heritage Program, part of the state Conservation and Natural Resources Department, has twice petitioned the state to list the buckwheat as a critically endangered species, which is separate from the federal designation. The state rejected the requests. Although the petition is being considered one more time, Mrowka said the plant can’t wait any longer for protection, so his group is pushing for a federal designation instead.

The designation would help protect 127 acres of buckwheat in the Upper Las Vegas Wash, an area of open land coveted by developers for its moneymaking possibilities and by conservationists for its natural resources, including the buckwheat, the rare Las Vegas bear poppy and Merriam bear poppy plants, petroglyphs and fossilized remains of mammoths and other ancient creatures.

It might also save a stand of buckwheat growing on public land at Tropicana and Decatur slated for a county park and acres of the plants on Nellis Air Force Base.

But conservationists’ concern is mainly focused on the plants and other natural and cultural resources in the Upper Las Vegas Wash.

Under the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act, about 13,000 acres of the wash have been designated for “disposal,” government-speak for sale to developers or transfer to another state or federal agency. Although the areas that contain buckwheat and fossils were not originally slated to be sold by the Bureau of Land Management when the act was created in 2000, they were added in 2002 in a process that critics say was less than completely open.

“It’s unfortunate that ... these things weren’t considered in a more open fashion when the expansion of the boundaries of (the act) were considered,” said Jeff van Ee, associate director of the Nevada Outdoor Recreation Association. “Lo and behold, people are finding themselves surprised at what’s out there.

“And some of that isn’t apparent when a staff person in Washington, D.C., looks at a plain old map and draws these boundaries. You have to get out there and see what’s on the land when you make these decisions.”

So now conservationists, hikers and archaeologists find themselves having to fight to preserve those special resources.

“It’s tough to stand in the way of people who think that almost every acre of land in the Las Vegas Valley should be developed,” van Ee said.

The BLM expects to release a preliminary environmental review of the 13,000 acres this summer. The review will eventually determine how much of that land should be preserved, who should take care of the preserved acres and what can be built on any land sold to developers.

Sharon Powers, president and chief executive of the North Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce, says a mere plant shouldn’t stand in the way of the economic engine that drives this valley.

“Where does it stop? We can have a great conservation area where all this land is protected, but if it doesn’t bring jobs and commerce into an area, what good does it do?” Powers said.

She said there is little scientific evidence to support claims that the buckwheat is its own species, exists only in the Las Vegas Valley and deserves federal or state protection. Protecting the plant, she said, would be premature.

“There’s a balance between going off the deep end and trying to preserve every plant that’s out there, as opposed to the economic well-being of our community,” she said. “We really feel at the chamber that this is just a tool that conservationists are using to control growth.”

Those conservationists point out that controlling growth, keeping it in check with the valley’s water supplies and ability to build adequate infrastructure, might be a good thing. And they say developers are getting ahead of themselves in assuming public land up for disposal should automatically go to them.

“Just because property is located within the disposal boundary doesn’t mean it has to be ‘disposed of’ and developed,” van Ee said.

Until the environmental review of the land is released this summer, Mrowka hopes to trip up the rush to develop by winning endangered status for the scrubby shrub.

That would, however, still leave the larger questions about sprawl, development and the valley’s future looming on the horizon, he said.

“As a community grows and matures, there are some things that become more important than the almighty dollar,” he said. “Don’t we want to start saving some of the special pieces that make our community unique?”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy