In 1979, Richard Bunker was tapped to head the Gaming Control Board. A devout Mormon, Bunker consulted trusted friend and religious icon James I. Gibson before accepting the job.

Sunday, June 1, 2008 | 2 a.m.

EDITOR'S NOTE: (Two decades ago a freshman Nevada congressman went calling on a cattle rancher in Northern Nevada. What would it take, Representative Harry Reid asked, for the rancher to sign off on plans to create a national park nearby.

Special Sun Series: Quenching Las Vegas' Thirst

Sun Archive Stories

- Historical Perspective — Desert oasis drying up: The Las Vegas Valley is seeking ways to squeeze every drop of water out of all available desert resources. (May 15, 2008)

- Water: The more you use, the more you’ll have to pay: In a region increasingly plagued by drought and water shortages, conserving water has become not only a virtue but the standard. How to get Clark County water users to live up to that standard isn’t entirely clear. (April 8, 2008)

- A problematic thirst: According to the report by the Great Basin Water Network and Defenders of Wildlife, if Las Vegas were to use 40 percent less water, a multibillion-dollar Southern Nevada Water Authority pipeline would be unnecessary. (Oct. 22, 2007)

It was a bold question. Officials had tried and failed for 60 years to win the support of ranchers to create Great Basin National Park. Now this new congressman was trying?

Indeed, he was sitting at rancher Dean Baker’s kitchen table in 1985, waiting for a reply.

You’ll have to protect our water, Baker said.

The Great Basin aquifer, which sweeps underneath the great parched desert of Southern Nevada, burbles to the surface up north, outside Ely, where Baker and other ranchers have lived for generations. Without water, their livelihood would end.

To Baker’s delight, Reid agreed. The water would be protected.

Reid and Baker met again 20 years later. The years had been kind to them. With water guaranteed, Baker was a wealthy man. Reid had moved up to the Senate and was on the verge of becoming majority leader, one of the most powerful posts in the nation.

The occasion of their meeting in July 2005 was the dedication of a new visitor center for the park the two men had had a hand in creating. But things had changed.

Las Vegas was in year six of a fierce drought. The booming town had nearly exhausted its allotment of water from Lake Mead. Soon, if nothing was done, Las Vegas, the economic engine that drives the state, wouldn’t have enough water to support growth.

So on this day, Reid asked Baker: “What are your water rights?”

Translation: Las Vegas needs your water.

Harry Reid and Dean Baker became adversaries.

How had it come to this? A thriving region of nearly 2 million people was running out of water even as the mighty Colorado River flowed just 30 miles away. What trick of geology and climate forced Las Vegas, a city with no reason to exist except for its historical ingenuity and daring, to go to survival mode once more?)

• • •

By Emily Green, Las Vegas Sun

Richard Bunker will not be judged.

As a Mormon bishop, he doesn’t gamble, he doesn’t smoke, he pays a full tithe to his church and he served a three-year mission in Finland.

A direct descendant of some of the region’s earliest pioneers and the son of a city councilman, Bunker too has dedicated his life to building Las Vegas.

As Clark County manager, Bunker streamlined the infrastructure of what went on to become the fastest-growing metropolis in America. Bunker then reinvented modern gaming.

In the process, he became a kingmaker in Nevada politics.

He vows that his last act for Las Vegas will be to keep it in water.

• • •

Las Vegas lies at the intersection of three deserts. To the west is the Mojave, to the south the Sonoran and to the north the Great Basin.

The Sonoran Desert marries California, Arizona and Mexico.

The Mojave is largely a Californian desert that spills into Southern Nevada.

Both are known as “hot” deserts, names that make more sense when it is 120 degrees in the summer than 10 below freezing on a winter night. Rains do come, but so rarely that the Sonoran’s saguaro cactuses and the Mojave’s Joshua trees have become international symbols of stoicism.

North of Las Vegas, the Great Basin Desert begins. It too is largely dry, but this is a “cold desert.” Its altitudes are higher, its winters longer and colder, and its valleys are fed largely by snowmelt. The Great Basin Desert covers most of Nevada and relaxes eastward across the Utah border to claim the oldest stretches of Mormon country.

As elevations steadily rise in the northward climb, the yuccas of the hot desert give way to a luminous green shrub called greasewood. The sheer brightness of its foliage screams a secret. Where there is greasewood, there is water.

There was ground water once in Las Vegas, but growth unmatched since the gold rush has consumed it. Today Las Vegas relies on water from the Colorado River, stored in the country’s largest reservoir only 30 miles outside the city.

But in the world of water, proximity to water doesn’t count. Historic claims do.

The biggest belong to California, the smallest to Las Vegas.

So to fuel its growth, Las Vegas has turned away from the Colorado. It now wants the water underlying the cold desert to the north.

To get it, a water authority in no small part built by the Bunker family is in its 19th year of slowly but surely moving to pipe that water south.

To Bunker, it is a historic duty to right a historic wrong.

To critics, it is the biggest urban water grab since William Mulholland plumbed Owens Valley to serve Los Angeles.

• • •

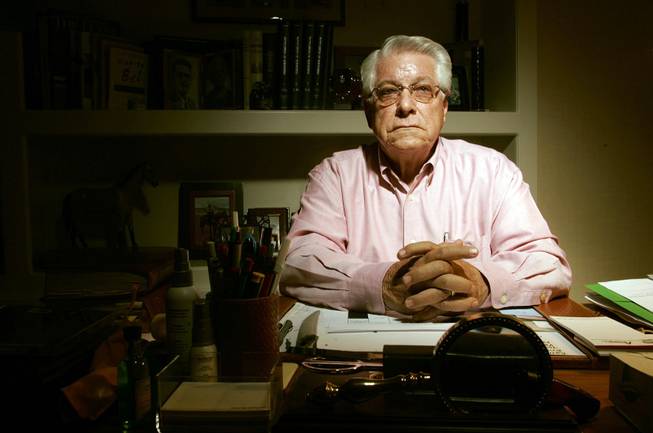

The thickset 74-year-old who enters a top-floor boardroom of the Southern Nevada Water Authority looks just like the figure captured over the years in newspaper photos.

There is the rich crop of hair, now silver, the sun-spotted skin and the watchful and watery (and it turns out gray) eyes. Bunker may have retired, but the handshake hasn’t. It is confident, firm but not crushing. Bunker has been around prying gentiles long enough to appreciate that his family story requires a disclaimer, which he delivers with high propriety: “My great-grandfather was a polygamist before the church came out with an order called ‘The Manifest,’ which forbids plural marriages.”

Richly framed photographs of that great-grandfather, Edward Bunker, and his first wife, Emily Abbott, hang in the original Mormon statehouse in Fillmore, Utah. According to a brisk and vivid account by the church historian Leonard Arrington, Edward converted to Mormonism in 1845, at the height of fervor about Joseph Smith’s martyrdom. Scarcely a year after his conversion and only months after his first marriage, Edward began the grueling march to California as part of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican-American War.

Edward barely made it home before the church sent him off to proselytize in Great Britain. He returned with a pack of Welsh converts, not one of whom he could understand. They spoke only Gaelic.

By the time Edward Bunker homesteaded his last colony for the church in 1877, he had been halfway around the world, had three wives and ended up in one of the most sun-blistered, hardscrabble bishoprics on the Mormon trail. At the suggestion of Brigham Young, his new colony on the Virgin River in the newly minted state of Nevada would be called Bunkerville.

From the comfort of an air-conditioned office and removed by more than a century, great-grandson Richard Bunker shakes his head at the thought of it.

“Brigham Young could have sent him anywhere,” he says. “He chose to send them to Bunkerville. There are lots of nice valleys in Utah and Nevada. But he sent us to hell in the desert.”

He’s not complaining, he adds. “It’s an interesting thing to contemplate.”

Moving water out of a river and spreading it across desert is as old as civilization. The ancient Persians did it. The Egyptians did it. The Romans did it, and as the West was settled, the Mormons did it.

They had no choice. Vigilantes had chased them out of Illinois over their founder’s promiscuity. Marc Reisner was only half-joking in his classic book “Cadillac Desert” that irrigation farming in the West is so fundamentally Mormon that when the U.S. government formed the Bureau of Reclamation in 1902 to put arid land under the plow, Reclamation was by extension Mormon, too.

But the Virgin River’s unforgiving salt, mud and moods defied even the most resolute Mormons. “During the rain, it would flood your crops,” Bunker says. “During the drought, your crops would burn up.” The poverty was so pervasive that Edward instituted the Mormon equivalent of communism, called the “united order,” in which settlers pooled their wealth.

The Bunkervillians dug irrigation ditches. They planted sorghum, alfalfa and vegetables. But the soil wasn’t good earth, Bunker says. It was “alkali dirt.”

The distinguished Mormon historian Juanita Brooks grew up in Bunkerville and her accounts lend sharp detail. The summer heat was so fierce, she recalled, that it “thickened the whites of eggs left in the coop” and made lizards “flip over on their backs and blow their toes.”

The church gave up on polygamy before Edward Bunker gave up on Bunkerville. Only after the 1890 manifesto ending plural marriage did he take his first wife, and Richard thinks also the second, to Mexico. But Richard’s great-grandmother, wife No. 3, moved west instead to St. Thomas, another Mormon farming community on another tributary to the Colorado River.

• • •

To understand why Richard Bunker or any deeply rooted Southern Nevadan despises Californians — and they do, oh they do — just follow the water.

As the unfettered Colorado River once tumbled out of the Rockies, it swelled to a massive force with infusions from tributaries in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. Steadily dropping elevations pushed it south through the canyons of Utah into Arizona, where it hung a sharp right West into the Mojave. There it etched the violent squiggle that breaks Nevada’s ruler-straight borders and pushes south again, through the Sonoran Desert, along the fretful front line between Arizona and California until it flooded into the Gulf of Mexico.

The state with the most natural claim on the billions of gallons of rushing snowmelt is Colorado, but in Western water law, origin is moot. Catching it and utilizing it is everything.

The 19th-century settlers who did this most successfully happened to sit farthest from the water’s origin, in the Sonoran Desert of California, in a natural sink located just before the river flows into Mexico. A succession of 49ers prospecting their way across what was then known as the Valley of the Dead looked at the rich soil from silt deposited by past floods and reckoned they needed only to build levees to have unimaginable wealth. They renamed it the Imperial Valley, dug miles of channels and persuaded thousands to settle there on the gamble that earthen dams could contain the river that carved canyons from stone.

The Colorado first swept away their head gates, then steadily eroded their levees as it poured into the California desert in such volume that it formed the Salton Sea. When the Imperial Valley emerged from the mud and chaos in 1907, the Californian mud farmers hadn’t harnessed the Colorado River, but a series of irrigation districts throughout the region had done the next best thing.

They had established a legal claim to the water. Under the law of prior appropriation, the first to claim the water had first rights to it.

Californians might have claimed the whole river had they been able to build a dam capable of containing it. But that would take cash as well as concrete that only federal money can buy. Before the federal government could be persuaded to step in and dam the lifeline of the West, California would have to agree to share the water.

That was a tall order. But in 1922, then-Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover resorted to jamming delegates from the seven states on the river into a remote New Mexican hunting lodge. He made sure that it was uncomfortable. They could come out when they agreed on a plan.

It did not go smoothly. Four states, dubbed the Upper Basin states — Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico — particularly held that the river, at least the part that passed through their territories, was rightfully theirs. Downstream, California and Arizona were close to war over tributary water.

Under the Colorado Compact and the act that six years later ratified it, the river basin was divided in half (with some treacherous exceptions). Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico, the Upper Basin, were allocated 7.5 million acre-feet of water. California, Arizona and Nevada were deemed Lower Basin states. They, too, came out of the enforced love-in with 7.5 million acre-feet of water, of which California received 4.4 million a year, Arizona 2.8 million and Nevada 300,000.

At the time, the puny share did not bother the Nevadan delegation. The ground water springs of Las Vegas had such force that they formed geysers. Two percent of a big river on top of that, or in modern terms, enough water to supply 600,000 single-family homes for a year, was a lot of water for a 1922 railroad town.

Umbrage came later. Only when Las Vegas began to outgrow its water did the Colorado Compact and its 1928 allocations come to be seen as a blunder, one that hits a regional nerve. Richard Bunker will tell you that it’s Northern Nevada’s fault. There were no Southern Nevadans at the table. Moreover, according to Bunker, the Northern ones just might have been drunk.

“There is no doubt that they imbibed,” Bunker says. “They followed almost to the letter the lead of the California delegation.

“For them to say 300,000 acre-feet was a lot of water for a place that was sand dunes, mosquitoes and rattlesnakes sounds fair,” Bunker says. “But when you look at what Arizona got, 2.8 million ...” he drifts off, then sighs. “It is what it is.”

• • •

The notion loosely held by Northern Nevada negotiators was that the Mormon farmers around Las Vegas might create a miniaturized version of the Imperial Valley.

That didn’t happen. As the Bureau of Reclamation began construction of Hoover Dam in 1931, Las Vegas became a staging area filled with construction workers whose needs could be largely summed up in a telephone book under B: boarding houses, brothels and bars. Moreover, that same year, Nevada legalized already prevalent gambling. Las Vegas added a C to its key services: casinos.

In short, the mob didn’t invent modern Las Vegas. The Bureau of Reclamation did.

By the time Bunker was born in 1933, his family had moved to Las Vegas. Their family farm at St. Thomas was sacrificed to the rising waters of the new Lake Mead. Las Vegas still ran on ground water, with springs all over the valley. “I used to swim in them,” he says.

His father and uncles became pillars of the community, serving on the city council and in the state Legislature and the U.S. Senate. But according to a touching eulogy for one of Bunker’s uncles given by Nevada Senator Harry Reid, they still managed to be just folk, small-towners who ran a gas station and mortuary and who pulled together to create the Las Vegas convention center and its Mormon temple.

Bunker himself made several stabs at elected office — for a seat on the county commission early on and another in the state Legislature later in life — but never won. He was perhaps too private, too proud and without a doubt something rarer: an audacious bureaucrat who became an unmatched political fixer.

After graduating from Brigham Young University with a political science degree in 1959, he went into sales for a rock and sand business. A decade later he’d become an analyst for Clark County. Next stop: head of the county’s automotive division, then jobs as assistant city manager of Las Vegas, county lobbyist and, in 1977, Clark County manager.

As lobbyist and then county manager, Bunker didn’t so much manage the place as reinvent it. “I had to replace the head of the building department, replace the fire chief and replace the head of the planning department,” he says.

Then in 1979, one of Las Vegas’ leading Mormon sons was tapped by the governor to head the Gaming Control Board.

Mormon proscriptions against gambling go back to Joseph Smith. But from the time a Salt Lake City financier taught the mob about bank accounts in the 1950s, an understanding for Nevadan Latter-day Saints was emerging: Just don’t touch the dice.

Bunker recalls wrestling over it this way: “I went to a friend, James I. Gibson, a religious icon here in the Southern Nevada area, and a state senator. I asked him, ‘Jim, what do you think I ought to do?’ My supposition is that he checked with his contacts in Salt Lake and they said, ‘By all means.’ We were better off being in a regulatory position over the industry than not being.”

The Gaming Control Board investigates applicants for gaming licenses. The Nevada Gaming Commission then issues the licenses. Heading the commission was another Latter-day Saint politician, a young Harry Reid.

Nevada was under pressure from the FBI and Congress to clear the mob out of Vegas before the federal government came in and did it for the state. It needed a blameless team.

Who better to grasp the nettle than two Mormons?

Except by June, Reid himself was beleaguered, presumed to be the “Mr. Clean” and “Mr. Cleanface” alluded to in FBI mob tapes unsealed in Kansas City.

One of Bunker’s earliest jobs would be, at Reid’s insistence, to investigate Reid, who, Bunker concluded by February 1980, had been the victim of “unmitigated character assassination.”

For the next year and a half, Reid and Bunker held hearings. Licenses were suspended. Names were put in the black book. A bomb was discovered in a Reid family car. Bunker sent his children to school with a police escort. Both men somehow survived the ridicule of 1981, when they announced they could find no evidence that Frank Sinatra was associated with the Mafia.

While Reid endured the derision quietly, Bunker snapped. The Bunkerville Bunker turned on the visiting press corps, delivering what The New York Times correspondent described as his “soliloquy.”

“This state over the last 46 years has been very good to me, and it’s because of the gaming,” Bunker said. “I personally don’t believe in gaming, but it has provided the livelihoods for thousands of people who raised their children in this state. We have an economy here that is based on something that is illegal to every other jurisdiction but New Jersey, and people coming into this area, whether they be FBI, whether they be whoever they are, might come in here with different ideas than what some of us think that have lived here all our lives.”

As Bunker tells it, Howard Hughes, Steve Wynn and Kirk Kerkorian, the modern models of casino owners, entered stage left as the mob exited stage right. The industry duly cleansed, Bunker went on to become treasurer of Circus Circus and president of both the Dunes and Aladdin hotels.

By 1990, Steve Wynn had opened the first megaresort, his competitors had half a dozen other huge ones on the boards, and Bunker was the head of the Nevada Resort Association and the most powerful gaming lobbyist in the country. One need only review Nevada’s generous tax law pertaining to gaming to appreciate his prowess.

But as New Vegas and its suburban skirt grew inexorably up and out, the problem was no longer the competition from Atlantic City, or whether Sinatra had hand-carried $2 million to Lucky Luciano, or mobsters skimming casino receipts, or who killed Kennedy.

It was water.

• • •

There was so much native ground water in early Las Vegas that not only did boys swim in springs, but according to Florence Lee Jones’ classic “Water: The History of Las Vegas,” homeowners routinely left town with their sprinklers running. Who knew that the local springs would be pumped dry?

As it turned out, a succession of state engineers knew.

By the 1950s, the valley had been pumped so hard that the ground was caving in beneath Nellis Air Force Base. Just as the golf courses began cropping up around casinos, the Strip had been pumped to capacity. Capping the wells and getting water users to hook up to a newly formed water system eventually killed the man who issued the battle cry. Months after the water stopped briefly in Las Vegas and state engineer Edmund Muth was driven from his job, he died of a heart attack. It was 1962, the same year the springs stopped flowing to the surface.

But right up to the point that he died, Muth insisted Las Vegas had ample water. It needed only to switch from ground water to Colorado River water.

As Las Vegas began the switch, Nevadans began wondering whether to revisit the Colorado River allocations fixed when the compact was ratified.

In 1952, it just so happened that Arizona was about to haul California clear off to the Supreme Court over its river woes.

Nevada hitched itself to the proceedings.

The logic: If the highest court in the land was revisiting terms for Arizona, why not ask for more water for Nevada? Twice as much? Three times!

As this giddy notion took hold a third of the way through a decadelong case, a reporter covering the trial concluded: “Thus far in the suit only one thing has been definitely established. There is not enough water in the Colorado River to satisfy the demands of the states and Federal Government.”

After the special master assigned by the Supreme Court to hear the arguments also had a heart attack (he lived), he recommended that the court deny Nevada.

In other words, between 1956 and 1962, the Supreme Court special master nearly died in the course of telling Nevada there wasn’t enough water in the Colorado River, and Nevada’s state engineer died arguing that all would be well if Las Vegas just moved its water source from ground water to the Colorado River.

As the population of Clark County hit 2 million late last year, Southern Nevada was stretching the last drops from its Colorado River allocation.

But Las Vegas had a backup plan: pumping the ground water of the Great Basin Desert.

This time the obstacle wouldn’t be California but Utah.

The Great Basin covers most of Nevada and half of Utah. To tap its aquifer, Southern Nevada must turn on the very heartland of the old Mormon state.

It fell to Bunker to represent Nevada’s need to Utah. In July, the governor of Nevada announced that Bunker had become the state’s “special negotiator” for the water under dispute with Utah.

Standing with him in a larger political press for it is his old confrere, Harry Reid.

Again, Nevada is trotting out its Mormons.

Again, Richard Bunker will not be judged.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy