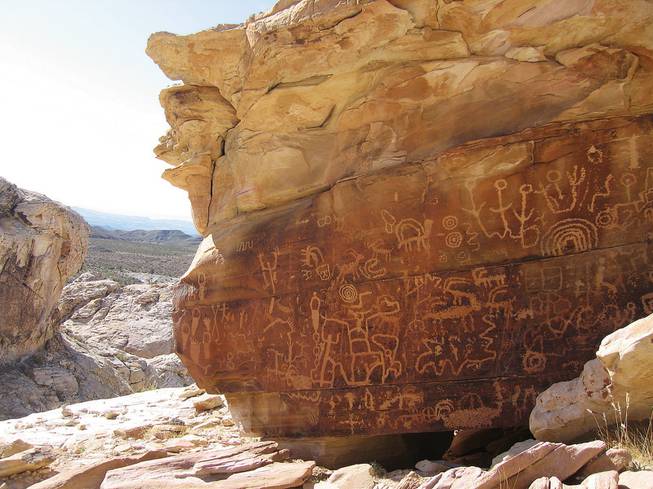

Nick Dobric / friends of Gold Butte

A petroglyph panel known as “Newspaper Rock” is among the areas in Gold Butte, near Mesquite, for which conservationists have pushed legislators to pass protections.

Wednesday, Nov. 12, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Reader poll

Sun Archives

- Letter: Protect precious Gold Butte region (10-3-2008)

- Letter: Gold Butte deserves federal protection (6-9-2008)

To get close to the copper-colored rocks of Gold Butte and the 1,000-year-old petroglyphs etched on them, it takes not only four-wheel drive, but a sturdy set of hiking shoes.

And that’s the way Gold Butte enthusiasts want to keep it.

Congresswoman Shelley Berkley, who visited Gold Butte for the first time in August, introduced legislation in late September to make the back country near Mesquite a national conservation and wilderness area. Her spokesman said the visit to what locals call “the Red Rock of Mesquite” won her over.

Indeed, for the first-time visitor, each turn on the bumpy dirt roads brings new visual wonders – a 100-year-old mining camp, rare plant species, mountains that dare you to climb them.

With the wilderness bill, Berkley, a Democrat, answered a call from conservation groups.

Wilderness advocates have celebrated a string of victories in this decade, which has seen more than 3 million acres of wilderness and national conservation areas designated in Nevada, including an old growth Joshua tree forest, parts of Red Rock National Conservation Area, Sloan Canyon, more of Mount Charleston and two small areas in Gold Butte, near Mesquite. But advocates said there was more to be done, including pushing for more protection around Gold Butte, an area 65 miles northeast of Las Vegas.

Off-road vehicles and vandals carrying out artifacts and leaving behind graffiti were moving faster than the federal government, John Wallin, director of the Nevada Wilderness Project, said at the time. Gold Butte needed the extra resources and enforcement efforts that would come with a conservation area or wilderness designation.

But that designation rarely comes without controversy.

Republican Congressman Jon Porter’s staffers shopped the proposal around for months to the rural communities near Gold Butte that are part of his district. While they did that, they asked the Nevada Wilderness Project and Friends of Gold Butte to keep private the pitch for a 360,000-acre conservation area that would include 220,000 acres of strictly protected wilderness.

Then, after the town advisory board in Bunkerville said it opposed the proposal, Porter’s office abandoned it.

So Wallin and his group took the idea to Berkley’s office, and she introduced the legislation Sept. 26. Spokesman David Cherry said the bill is not likely to be considered until next year and may change with input from rural communities before then.

Although some foes of the wilderness designation have criticized Berkley for proposing legislation to designate a wilderness and conservation area in Porter’s district, Cherry said introducing the legislation was an effort to get the public involved and start the discussion about how to improve the proposal.

“People misinterpret the bill,” said Tom Collins, a Clark County commissioner and Democrat who represents the Gold Butte area and parts of Mesquite. “Congress is going to make sure the local folks have complete input into this thing before anything is passed.”

Representatives of the rural communities near Gold Butte would make up about half of a committee in charge of creating the conservation area’s management plan.

The main objection to the wilderness designation is that vehicle access to the area would be limited.

The wilderness designation prohibits off-road use of any kind of vehicle, including all-terrain vehicles, bikes, wheelchairs and everything in between. It allows camping, hunting, fishing, hiking, horseback riding and other uses, though.

Doug Nielsen, a freelance writer and outdoorsman, says although areas of Gold Butte certainly need protection, the wilderness designation is overly restrictive.

“We have gone from a place where we could feel free to move about ... to an area where if I don’t have the right pass I can’t go there,” he said. “And it’s all publicly owned land.”

Limiting vehicle access to existing roads, Nielsen said, would prevent all but the youngest and strongest of visitors from getting close enough to Gold Butte to enjoy it.

“A wilderness designation is the most strict land use outside of military that you can come up with,” he said. “You can still get in there if you’re young, or in great shape ... But if you’re an average American and you would like to go see that country and there is already an existing road or trail there, why does that have to be closed off to them?”

The bill neither closes nor opens any roads, however. A Bureau of Land Management plan 10 years in the making, however, will preserve 480 miles of existing rough roads and close another 90 miles. The remaining roads, many of which require a sturdy four-wheel-drive vehicle, will not be improved under either the BLM management plan or the wilderness and conservation bill.

Off-roading, in fact, is already prohibited in the area, since it’s been identified as prime desert tortoise habitat. But that restriction hasn’t been enforced to the degree that it would be under a wilderness area designation, conservationists say.

The additional 132,000 acres of desert tortoise habitat that Berkley’s bill would effectively create would help Clark County comply with the Endangered Species Act, Clark County Manager Virginia Valentine has noted. And, because the county has an agreement with the federal government to protect habitat for threatened or endangered species while allowing development elsewhere, if the Gold Butte proposal wins approval, that would allow more development elsewhere in the county.

That’s just more bad news for Nielsen and other Clark County residents who would prefer to have the run of wide open spaces, a preference squelched, to varying degrees, not only by new neighborhoods but by the amount of land in the county that is consumed by the military, a wildlife refuge, conservation areas and recreation areas.

Wilderness areas currently make up only 4.8 percent of Nevada’s land area, according to Nick Dobric, Southern Nevada outreach director for the Wilderness Project. If this latest bill passes, 5.1 percent of Nevada will be designated wilderness. But 87 percent of Nevada land is federally owned, including the 67 percent of the state managed by the BLM.

In fact, conservationists say protecting Gold Butte may attract visitors, rather than scaring them away, and advancing the legislation walks a fine line between promotion and protection.

While gathering support for the conservation proposal by extolling Gold Butte’s virtues, the area’s most ardent fans also want to protect its more vulnerable natural and historic features.

Nancy Hall, president of Friends of Gold Butte, which worked with the Wilderness Project on the bill, said visitors are coming anyway, whether the area is protected or not, and it will be increasingly important to educate them about treading softly while they’re there.

“It’s a double-edged sword. It’s still difficult for me to take people to certain places, and there are just some places I wouldn’t take somebody,” Hall said. “You don’t want anyone else to know about it, but you can’t get anything else done unless you tell.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy