The Oasis Golf Club is one of six golf courses in Mesquite. Another golf course is set to open soon.

Sunday, Aug. 23, 2009 | 2 a.m.

In Today's Sun

Deliberate growth amid boom reflects Eureka owner’s heritage

Greg Lee on Mesquite

Greg Lee, owner of the Eureka Casino Hotel, talks about the history and growth of Mesquite.

Audio Clip

- Mayor Susan Holecheck talks about Mesquite's city finances.

-

Audio Clip

- Holecheck on why the city is doing well.

-

Audio Clip

- Holecheck talks about why residents like Eureka Casino Hotel.

-

Audio Clip

- Holecheck on "what recreation can bring to the table."

-

Audio Clip

- Realtor Roger S. McDonald talks about the real estate market in Mesquite.

-

Audio Clip

- McDonald explains why buyers in Mesquite are more secure than in Las Vegas.

-

Audio Clip

- McDonald on where buyers in Mesquite come from.

-

Sun Topics

Sun Coverage

Sun Archives

- Black Gaming warns again of possible bankruptcy (8-14-2009)

- Down economy means tourism suffering statewide (8-14-2009)

- Mesquite casino cites economy in reduction (12-2-2008)

Beyond the Sun

The parking lot of the Oasis Resort Hotel & Casino is empty, heat blasting off it, mocking the name of the now shuttered hotel. The go-cart track is silent and the pool closed, its deck chairs stacked, giving the place the feel of a wintry Rust Belt amusement park.

For small communities in Southern Nevada like this town on the Arizona border, the troubles in Las Vegas are a contagion. The Oasis, owned by Black Gaming, once offered affordable rooms to travelers on the I-15 corridor, the first party stop in Nevada.

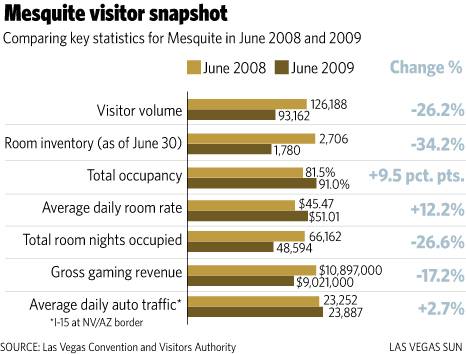

Now, though, Strip casinos are practically giving away rooms to entice gamblers. This has pummeled Mesquite, which had 26 percent fewer visitors in June than in June 2008.

The sharp drop in visitor volume, combined with an extraordinary debt load, forced Black Gaming, the dominant player in this market, to close the Oasis late last year and lay off 500 workers — a huge hit in a town of 20,000.

But there’s more to Mesquite than a few casinos and that nasty Las Vegas effect. The city, incorporated 25 years ago, is like a patient trying mightily to fight the infection with a combination of creativity and grit.

It may be working. And the town’s future may lean on a different sort of gaming.

In December, a Mesquite city staff member told Mayor Susan Holecheck about a big new sports complex planned for Hurricane, Utah.

“I said, ‘Why Hurricane?’ ” she related in an interview last week.

So Holecheck’s staff tracked down the developer and the mayor, who has the forceful charisma of a class president, went into pitch mode: Mesquite has plenty of cheap land, a good base of existing recreational facilities, lots of hotel rooms and quick access to McCarran International Airport.

When all was said and done, Utah-based Desert Falls International Sports Resorts Developers, which includes basketball great A.C. Green, agreed to buy 864 acres of city property for $6.3 million, with some other financial inducements for the city.

This week, a 5 percent down payment is due. “I’d like to believe it’s very solid, but banks scare me sometimes,” Holecheck said.

If it moves forward, the $125 million first phase would include 24 soccer fields including a stadium field, 20 softball fields, and 16 tennis courts and a stadium tennis court. Youth and adult teams, the city and investors believe, will converge from around the world to play their tournaments here, staying in the now shuttered hotels and even some new ones. Future phases of the plan would go bigger, with a minor league-quality baseball stadium, residential construction and a sports medicine complex.

If built, the facility would complement a newly opened soccer complex that doubles as a golf driving range. It is nestled into the red rock and will make a nice television image for October’s World Long Drive Championship.

As the salmon colored sky gently darkened overhead, Stan Nickle hit one down-the-middle bomb after another. “Just wish I could do this on a real course,” he said.

He built 26 houses during a recent three-year stretch, but the work has slowed considerably, to just a house or two per year, he said.

The Mesquite real estate market has suffered, though nothing like in Las Vegas. There are about 8,300 housing units in town, and currently about 500 properties are on the market. Of those, 72 are short sales or foreclosures.

A blunt and conspicuous billboard greets drivers as they come into town, imploring them to take advantage of bank-owned buying opportunities.

But Mesquite home buyers are a different breed than those in Las Vegas, said broker Roger McDonald: They tend to be retirees who pay cash or make significant down payments, which has meant fewer foreclosures.

Another thing about Mesquite residents, if a tour of four foreclosed homes is a reliable guide: Even when they default, they leave the homes in good condition.

It seems, for instance, the former owners of a house on Canyon View, listed at $189,500, even shampooed the carpets before leaving.

As broker Cathy McDonald noted, “It’s a small community” — word of a trashed house would get around.

This refusal to rip out appliances and copper wire has probably helped preserve value for everyone else. Prices have fallen 32 percent since the 2006 median price of $294,500, far less than the 58 percent crash in Las Vegas.

Business has been brisk this August, brokers say.

All is not well, however.

Sally Coates, who runs the senior center, said 120 to 180 meals are served daily on average, with another 100 prepared for the homebound. City fire and rescue workers help serve the meals until they get a call.

Business is up, Coates said, surmising that some retirees with modest nest eggs were wiped out by the bear market.

Randy Schwartz, a Navy veteran at the senior center lunch who is organizing a big pinochle tournament to benefit Special Olympics, worries that Mesquite “will become a ghost town” following a recent warning by Black Gaming that bankruptcy could be imminent. (Black Gaming declined interview requests.)

“It’s the only jobs in town,” he said, exaggerating a bit.

(Black Gaming’s competitor, the Eureka, is doing well.)

Charlotte Alsman, director of the Salvation Army, seems to know every troubled and impoverished family in town. The retired teacher manages a thrift store and social service agency, as well as a food pantry, which is stocked with neatly organized and colorful canned goods — beans, peas, peaches. One morning last week, she was busy handing out car seats and showing young parents how to install and use them.

She also teaches a parenting class. One girl is 14.

The laid-off Oasis workers who still live here — many left — are struggling, Alsman said. Child abuse is on the rise, she said with sadness. Thankfully, “This town gives back.”

There is, indeed, an aw-shucks, let’s do it attitude, worthy of a Christopher Guest satire, in Mesquite.

(New city motto: “Mesquite means business.”)

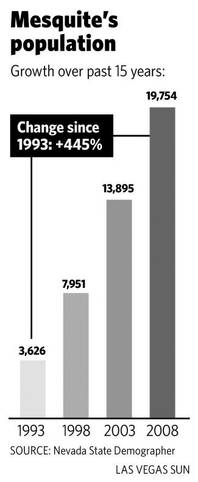

Bryan Dangerfield, the city’s caffeinated economic development director, marvels at the city’s growth. In 1990, the Census Bureau recorded fewer than 2,000 souls here, one-tenth the current winter population.

Dangerfield is working to make Mesquite more than an I-15 stopover and retirement community with good golf courses, by pushing a multipronged approach. The Obama administration has set aside federal land near Mesquite for renewable energy development. The city, working with private developers, built a 680-acre “Technology and Commerce Center,” which focuses on warehousing and light manufacturing and is home to a major hardware distributor. With the economy down, some of it sits unused for now.

There are plans for a new airport.

But Dangerfield’s real passion is recreation and turning Mesquite into a place known for sports and adventure.

“You come down into this valley, and it’s special,” he said. Some of the nation’s most beloved national parks are near here.

In addition to the long-drive golf championship, Mesquite will host its first marathon in November.

Solstice, a resort community planned though not yet built, advertises in this crunchy, sports-and-adventure vein — “envisioned to nurture the body, the soul and the spirit.”

Solstice would rest north of I-15, joining the sports complex, the hospital and Sun City Mesquite, where 500 upscale homes have been sold since early last year, according to the mayor.

It’s leapfrog development, the kind of classic sprawl now roundly condemned by urban planning experts and environmentalists for being auto- and carbon-intensive and failing to create real community.

For some here, this highlights an uncomfortable trend: The bifurcation of Mesquite, with the wealthy residing in the hills north of the highway and the working classes down in the valley, amid fast food, check cashing stores and now shuttered casinos.

Mayor Holecheck acknowledged that concern and said the city is to trying to address it with new infill developments. But then, with notable excitement in her voice, she compared the new growth north of the highway to the Summerlin area of Las Vegas.

As Mesquite grows, its residents will have to decide whether they want Las Vegas to be their model.

Sun reporter Alex Richards contributed to this story.

CORRECTION: This story was changed to correct the name of Mayor Susan Holecheck. The Sun regrets the error. | (August 24, 2009)

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy