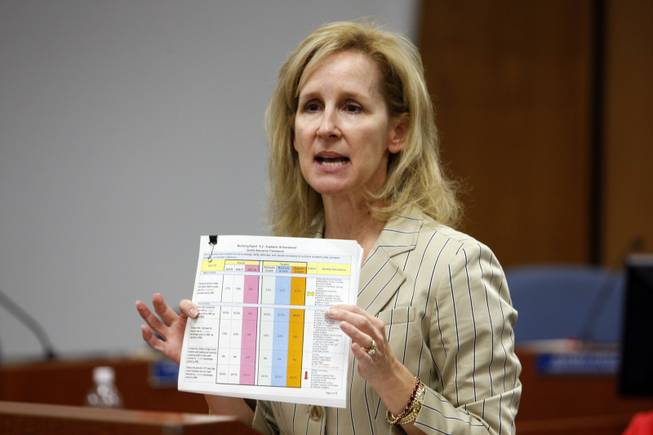

Lauren Kohut-Rost, a Clark County School District deputy superintendent of instruction, holds a monitoring report on academic achievement during a news conference at the at the Greer Education Center,Thursday, July 23, 2009. Clark County School Board members announced that the district had fallen short of “adequate yearly progress” under the federal law for the 2008-09 academic year.

Published Thursday, July 23, 2009 | 2:08 p.m.

Updated Thursday, July 23, 2009 | 2:54 p.m.

Related Documents (.pdf)

Sun coverage

When it comes to No Child Left Behind, “close” isn’t good enough, the Clark County School District learned today.

At a press conference at the Greer Education Center, Clark County School Board members announced that the district had fallen short of “adequate yearly progress” under the federal law for the 2008-09 academic year. The district had made adequate progress in 2007 and 2008.

Overall, the district’s test scores were high enough to satisfy the state’s benchmarks, even though there was a slight dip in math at the elementary level, and in math, reading and writing at the high school level. But the district -- as well as individual schools -- must also meet benchmarks for subgroups of students, broken down by ethnicity, special education status, limited English proficiency and those qualifying for free and reduced-price meals.

The district missed the mark in a number of those areas across all grade levels.

The "all or nothing" reality of AYP "has always been a frustration," said School Board member Sheila Moulton. "Our students have made tremendous progress but that sometimes gets lost in the message."

At the same time, Moulton said she doesn't want to see No Child Left Behind abandoned in its entirety.

"It's made us really look at every single child," Moulton said. "I'm grateful for that."

District officials said budget cuts might have played a role in the poorer showing because of larger classes and less support for students. Another factor, officials said, might also have been changes to the tests given to elementary and middle school students, said Lauren Kohut-Rost, the district's deputy superintendent of instruction.

Less money meant fewer opportunities for remedial students to get extra help and an increased workload for teachers, she said.

"Our superintendent tried to keep the budget cuts as far removed from the classroom as possible," she said, "but there's still an effect."

Clark County Schools superintendent Walt Ruffles was absent from the news conference. He had informed the School Board earlier this summer that he would be traveling at the time the AYP results were announced.

Schools have to demonstrate achievement in 37 different categories. Of the district's 361 schools, 171 didn't make adequate progress. Of those schools, 38 missed in just one subgroup area, while 37 others missed in two subgroups.

Among the bright spots in the results, Valley High School was singled out for special recognition as the district’s first-ever “turnaround high achieving” campus. The designation is reserved for schools that have spent at least three years on the “needs improvement” list before demonstrating high achievement. Fewer than 10 campuses statewide have received the designation.

Agassi College Preparatory Academy, one of eight charter schools sponsored by the Clark County School Board, also scored well. Agassi’s elementary students made adequate progress, while the middle school and high school were both high achieving.

Districtwide, 11 campuses were rated high achieving and six high school programs were recognized for continued exemplary achievement. The latter category is new this year, added by the Nevada Education Department to honor campuses that hit No Child Left Behind’s glass ceiling for top designations.

Supporters of the education reform law say it has brought renewed accountability, and forced districts to focus on struggling students who were often ignored. But critics say the law is too punitive, and that many of the requirements it imposes are unrealistic.

No Child Left Behind is up for reauthorization this year. But state education officials say they’ve been told no revisions or changes will be handed down before 2010.

In Clark County for the 2008-09 academic year, reading and writing proficiency was up about 2 percentage points in the elementary schools, while the same students saw their math proficiency scores drop by a similar percentage.

The district’s middle schools showed the most improvement, with 2 percentage point gains overall in reading and writing, as well as math. At-risk students in the middle schools also showed improvement. Scores for students qualifying for free and reduced price meals were up about 5 percentage points in all subjects. Hispanic middle schoolers gained 4 percentage points in reading, writing and math. Black students also did better, gaining about 2 percentage points in reading, writing and math.

At the high school level, the district’s performance in reading and writing slipped about 1 percentage point, although overall scores were still good enough for adequate progress.

However, there was a 5 percentage-point drop in math proficiency at the high schools, although the districtwide number still exceeded the state-mandated benchmark.

This year 234 schools made adequate progress in mathematics, compared with 263 last year. For a second consecutive year, 212 schools made adequate progress in reading and writing.

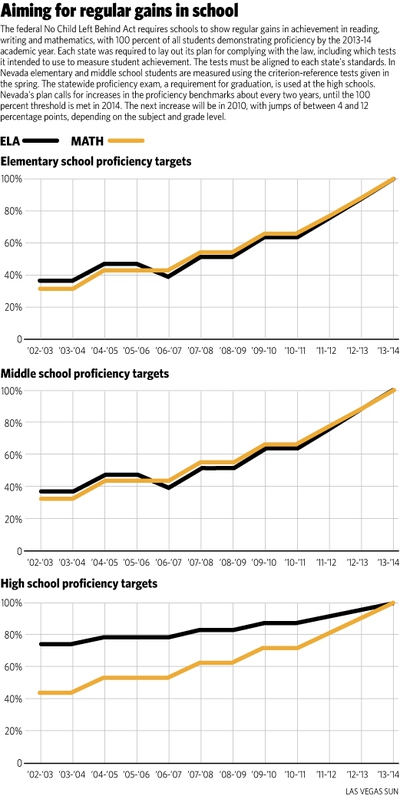

No Child Left Behind requires 100 percent of all public school students to demonstrate proficiency in reading, writing and mathematics by the 2013-14 academic year.

States were given some leeway in determining their paths to that goal with some, like Nevada, opting for increases in minimum scores on standardized tests about every two years.

Elementary schools and middle schools are judged using criterion-reference tests, while high schools are rated based on results from the Nevada State High School Proficiency Exam.

Schools that miss the test score targets but reduce the number of nonproficient students by at least 10 percent are considered to have made adequate progress under the state's "safe harbor" provision.

Failure to make adequate progress can result in sanctions, ranging from having to offer students transfers to more successful schools to being required by the state Education Department to replace key staff, including the principal.

This year the district has 14 schools on the “needs improvement” list for a sixth consecutive year. Von Tobel Middle School is in its seventh year on the list, which increases the likelihood of the state calling for significant program and staffing changes at the campus.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy