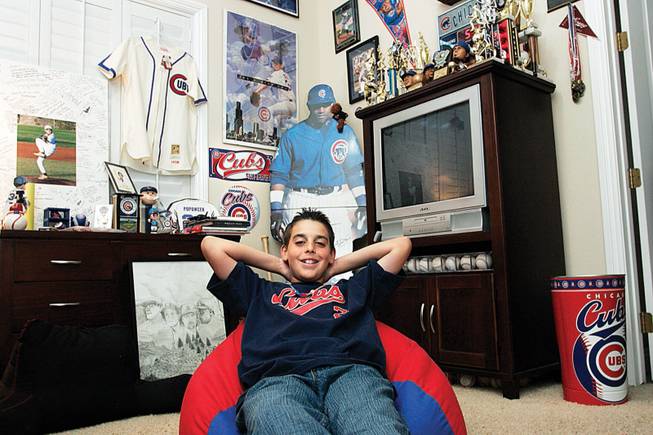

Liberty High junior varsity pitcher Ryan Popowcer’s room reflects the dedication to the Chicago Cubs he shares with his dad.

Tuesday, Oct. 27, 2009 | 2 a.m.

“I’d rather be the shortest player in the majors than the tallest player in the minors.”

— Freddie Patek, 5-foot-5, 148 pounds

Ryan Popowcer does not a throw a baseball with a great deal of velocity like Nolan Ryan, Don Drysdale or Roger Clemens did, mostly because those guys stood 6-foot-2, 6-foot-6 and 6-foot-4 respectively, and weighed 200, 216 and 220 pounds.

They had legs like locomotive pistons and arms like bazookas.

Ryan Popowcer, age 14, stands 5-foot-1 and weighs 90 pounds. He has legs like pipe cleaners and arms like pipe cleaners. He hasn’t yet experienced his growth spurt, so it can be assumed he’ll get taller and heavier. He can’t wait to find out. Neither can his parents, Sam and Ilene.

But judging from the size of his parents, it would be hard to imagine that Ryan Popowcer will grow up to be as big and strong as Nolan Ryan or Don Drysdale or Roger Clemens.

Right now, he’d settle for Freddie Patek.

• • •

I saw Ryan Popowcer pitch for the Liberty High junior varsity in a fall league game the other day. He wasn’t hard to pick out. He hasn’t been hard to pick out since Little League, where at least a few of the other kids were his size.

Unlike Freddie Patek, who wore jersey No. 2 with the Royals, Popowcer wears No. 1. Apparently, the Liberty High junior varsity doesn’t have a descendant of Cookie Rojas playing second base, so No. 1 was available. Kids Ryan Popowcer’s size never wear a high number because at the high school level, the high numbers, the pitchers’ numbers, go to the big kids, who, no coincidence, usually are the pitchers, too.

Popowcer’s number looks more like a hyphen turned vertical. The bottom part of the “1” appeared to be tucked into his baseball pants.

It seemed to take every ounce of muscle and tendon and fiber in his 90-pound body to propel the baseball the 60-feet, 6-inch distance of a pitch. His “fastball” would be ideal in an energy crisis because it travels at 55 mph.

When Nolan Ryan pitched in Chicago, old Comiskey Park reverberated with the sound of heat-seeking missiles striking leather, especially early in the season, when the leather in the catcher’s mitt was not yet supple.

Ryan Popowcer’s pitches tumble to and fro on their way to home plate, like Downy-soft towels in a dryer, with the difference being that Downy-soft towels tumble indeterminately, with no apparent location in mind. Little Ryan Popowcer seemingly can make his pitches cling to a sock in the fluff cycle, provided the sock is tumbling somewhere near the outside corner.

The kid is a control freak. Fourteen-year-old kids who pitch baseballs after school generally aren’t regarded as control freaks.

Popowcer retired the side in the first inning on 10 pitches. It took him nine pitches in the second inning, six in the third. He allowed two hits in his five-inning stint. No walks. One strikeout. He threw 48 pitches, most of which resembled the gravity-defying slowball with which Bugs Bunny mesmerized the Gashouse Gorillas in that old cartoon.

David Seccombe, the former UNLV right-hander, has taught him a slurve and a slow slurve, which Ryan calls a change-up. He also has taught him that what’s between a pitcher’s ears is more important than what’s in his soup bone, and this was even before Mike Scioscia summoned Scott Kazmir from the Angels’ bullpen on Sunday night.

In the game I watched, Ryan Popowcer was more efficient than a Prius with new points and plugs. You could almost hear the hitters muttering to themselves as they trudged back to the dugout.

Just think what they might have said if they knew Ryan Popowcer was born with a backbone that is shaped like a Slinky.

• • •

A few hours after throwing his 48th pitch to complete a two-hit shutout, Ryan Popowcer stretched out on his bunk bed so his mom Ilene could help him wriggle into a brace that in theory will reshape his spine. Ryan inherited this condition, called scoliosis, from his mother. Ilene Popowcer had to wear a fiberglass brace similar to her son’s for 23 hours every day from the time she was 9 until the time she was 13.

Ilene’s brace extended a little higher, where it was noticeable through her clothes. In that way, Ryan is fortunate. Teenage kids can be brutal sometimes. Plus, Ryan has to wear the brace for only eight hours a day instead of 23.

His father says Ryan doesn’t invite pals over to the house for sleepovers anymore — not because he’s self-conscious about wearing the brace, but because he is so meticulous about wearing it. Talking to your pals about baseball or girls late at night, even for a little while, would slow his progress, which so far has been amazing.

Besides, the brace fits so tightly that he couldn’t talk about baseball or girls, even if he wanted. Imagine Mark McGwire, before he was off the juice, sitting on your chest.

When a routine test revealed Ryan’s scoliosis 18 months ago, the curvature in his spine was 24 percent. Now it is 16. Doctors say if he can keep it under 30 percent, he won’t require corrective spinal surgery. Those can be delicate. Those could curtail a budding baseball career.

In the back of their minds, the Popowcers knew it was possible that Ryan would inherit the condition. But at the same time they were hopeful he wouldn’t. Their daughter, Ilyssa, a standout tennis player at Coronado High, had received a clean bill of health when she was tested.

“I was very scared,” Sam Popowcer said. “I got a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach — what’s gonna happen?”

What about Ryan?

“He doesn’t show a lot of emotion,” his father said. “I was more shaken up than he was.”

• • •

Ryan Popowcer appears even smaller standing in the living room of his parents’ home in Anthem with the Astrodome-height ceilings. On this day, he is wearing a T-shirt with Ryan Theriot’s name and number on back. Theriot is the shortstop for the Chicago Cubs, Ryan and his dad’s favorite team. He’s a little guy, too.

But his idol is Greg Maddux, another former Cub. There is a picture of young Ryan and a younger Greg on the wall of his bedroom, which looks like a Cubs bobblehead doll factory. Judging from the number of jiggling heads, the only bobblehead of a former Cubs player that Ryan hasn’t collected is that of Carmen Fanzone, the former trumpet-playing utility infielder.

He tells a visitor that his goal, besides returning his backbone to its full upright position, is to pitch on the Liberty High varsity as a sophomore next year.

“I like hitting my spots, getting the hitters to hit ground balls,” he said, sounding a lot like the guy with whom he had his picture taken while in Little League.

It seems far-fetched to believe that a 5-foot-1, 90-pound, 14-year-old high school freshman with a crooked backbone could think his way into the major leagues someday by throwing a baseball around hitters instead of past them.

But on June 20, 1980, a little 5-foot-5, 148-pound guy who spoke with a high pitch, like a jockey, became just the first shortstop since Ernie Banks to hit three home runs in a major league game.

His name was Freddie Patek, and on that day nobody in the Big Leagues stood any taller.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy