Giselle Sanchez, center, Carolyn Graham, left, and Belinda Brooks are among 13 operators statewide who field calls to Nevada’s 2-1-1 help line, which tries to match people in need with public services.

Wednesday, Oct. 28, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Nevada 2-1-1 manager Carol Filburn says increased call volume and emotions have affected her staff. "They would listen to crying all day and then they would come into my office crying," she said.

Sun Archives

- More welfare going to parents here illegally (10-27-2009)

- Increasingly, not just the poor are uninsured (4-27-2009)

- As economy worsens, tenants squeeze in (4-6-2009)

Beyond the Sun

- Nevada Department of Health and Human Services: Nevada 2-1-1

She can feel what the callers on the other end of the line are feeling. Recently it’s been tearing, gripping, throat-tightening.

Giselle Sanchez and 12 other call center operators spend all day answering questions about where to find help. Sometimes it’s help with the rent. Other times it’s help steering away from suicide.

These call-takers are the backbone of Nevada 2-1-1, a toll-free information service that United Way runs here and in 45 other states. Callers to the number in Nevada reach a portal for more than 7,000 social services available statewide.

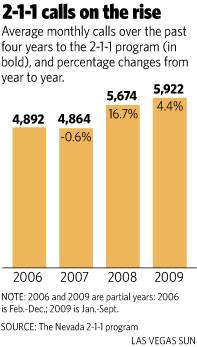

Since the economy tanked, more Nevadans than ever are dialing the number, and they are more eager for help, Sanchez and her colleagues said. As of Tuesday, the count was more than 6,000 in each of the past five months, a first for the 4-year-old program. And since 2007, when the recession began, the average number of monthly calls has increased 22 percent.

News accounts suggest it’s a trend being seen across the country, at 2-1-1 programs from Palm Beach, Fla., to Orange County, Calif.

“People are desperate,” said Mary Liveratti, who oversees the program for the state, the source of most of the program’s funding. “They are looking for help meeting basic needs, like food, clothes, a place to live.”

They are also pleading for information about finding work and avoiding foreclosure, said Carol Filburn, who manages the program’s day-to-day affairs at HELP of Southern Nevada, where nine of the state’s operators work from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays. Operators in Reno answer calls from 4 p.m. to midnight and from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekends. They all have access to the same database, the source of their referrals.

Filburn said the increased volume — and emotions — have taken their toll on the Southern Nevada call-takers in recent months.

“They would listen to crying all day and then they would come into my office crying,” she said. The director decided to bring in a counselor for monthly meetings with the operators.

Sanchez, who sits in a tight room with five chairs, computers and phones, needed to put a recent call on hold while she cleared tears from her cheek and the lump in her throat. The woman on the other end was, like her, a mother of three. The caller had lost her job. She had lost her husband, after he lost his job in construction and left the house. The caller then lost her house.

“I’ve been a bad mother,” she told Sanchez, asking whether there was an agency that could take care of her three little girls. Sanchez put her on hold, recovered her wits, and told the woman, “I know how you feel. But there are other alternatives.” She gave the woman information about sources of help with her financial free-fall.

The call center operator’s eyes teared up as she recounted the conversation.

Sitting nearby, colleague Belinda Brooks said some people call and say they can’t believe they’re even asking for help, because they’ve always been among the well-off. Sanchez has gotten calls from people who, in past years, donated to the same sorts of organizations from which they now seek assistance.

Both mentioned that the desperation they feel from callers is often compounded by the frustration of having to tell them that no help is available, say, for the rent, because a program’s funding has run out.

The 2-1-1 staff attempts to find out which programs are working well. They call 3 percent of their callers back within three weeks, to find out whether the information offered to them was useful. About one in four say yes. There is no detailed information about why the rest say no, but Filburn figures that one reason may be that many callers wind up being ineligible for the services they seek. She said her staff also attempts to update its database constantly, based on research into new programs and updates from callers about changes in existing ones.

Liveratti would like for the program to have more funding, of course, to hire more operators and to do more research. She said the program staff may not always have time to keep up with information such as new programs coming out of stimulus funding. She admitted that the program didn’t know to inform callers about the recent weekend visit of the Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America, a nonprofit organization on a national tour. The organization helped some 40,000 Nevadans modify their mortgages in a three-day period.

But even while need is greater, the program has suffered funding cuts. In the same period that its caseload has exploded, the annual budget has dropped from $643,622 for the 2007-2008 fiscal year to $583,266 for the current year.

Meanwhile, 2-1-1’s operators continue to try to guide Nevada’s unhinged and often hopeless to some kind of help. And Filburn tries to maintain staff morale, even when they have no answers.

“Sometimes,” she said, “you have nothing to give.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy