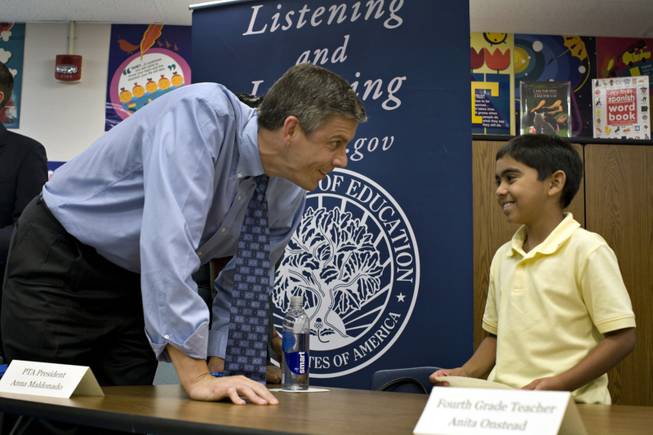

Education Secretary Arne Duncan, left, talks with fifth grader Stephen David after a “Listening and Learning” forum last week at Harley A. Harmon Elementary School in Las Vegas. Duncan says some schools “simply aren’t meeting the students’ needs,” which is why a $3.5 billion school improvement program calls for significant changes.

Wednesday, Sept. 2, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

- School District again taking heat for unequal achievement(8-16-2009)

- District announces three new empowerment schools(2-9-2009)

- Airing of charter tensions set (2-20-2008)

- Empowerment schools get extra money, resources (9-25-2008)

- Empowerment money mystery (6-14-2007)

- Empowerment schools forced to take a turn (4-20-2007)

- Charters aimed at minorities (8-7-2006)

Sun Coverage

Beyond the Sun

At first blush it looks like a boon for the Clark County School District:

The U.S. Education Department is offering tens of millions of dollars that could potentially be used to expand the district’s popular — and expensive — initiative to empower schools with money and autonomy.

But a closer reading of the fine print suggests the district won’t be able to tap the money to turn an unlimited number of campuses into empowerment schools.

To encourage districts to consider more aggressive methods of campuswide reform — including shutting down the worst-performing schools — the federal government is setting limits on how many schools can qualify for the new funding using the same approach.

“There are schools that simply aren’t meeting the students’ needs,” U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan said in a recent interview with the Las Vegas Sun. “We’re challenging folks to say, ‘More of the same isn’t going to get us where we need to go.’ ”

In the long run, forcing the district to confront such a harsh reality might be the new initiative’s biggest boon for Clark County’s students.

The $3.5 billion school improvement program will require districts to follow one of the approved “turnaround models” for its campuses ranking in the bottom 5 percent for academic performance. In Nevada, about 35 to 40 schools are expected to qualify.

One of the models approved by the feds — turning a public campus into a charter school — is prohibited by state statute. And the feds’ option of hiring a private operator isn’t likely to appeal to Clark County, given that Edison Schools Inc. hasn’t been able to show better-than-average achievement at the six elementary schools it currently manages.

The remaining options are to remake a school by replacing the principal and at least 50 percent of the staff; to implement a new philosophy (such as empowerment); or to close a school outright and use federal money to provide transfers to more successful campuses.

There is some suspicion among West Las Vegas residents that the district intends to close several of the community’s elementary schools, which have been part of a long-standing initiative that was intended to promote choice and diversity. A recent independent review of the “Prime Six” schools found test scores were significantly lower than the districtwide average. And most West Las Vegas students who opted to attend campuses outside their neighborhood scored higher in math, reading and writing than their peers who chose to attend the Prime Six schools.

The proposed requirements of the grant program, which will give out $546 million nationwide this fiscal year, include prohibiting districts with at least nine “turnaround” campuses from using the same strategy at more than half of them.

Since 2006 the district has been experimenting with empowerment, which provides principals with extra funding and more control over daily operations, including scheduling, staffing and instruction, in exchange for stricter accountability. With limits set on how many “turnaround” schools could be restructured into empowerment schools, the district would be forced to consider one of the more drastic courses of action on the feds’ short list of approved models — closing down failing campuses.

Each state will decide how to identify its lowest performing schools. The first priority is supposed to be campuses that receive federal Title I federal funding, for large populations of students from low-income households. Keith Rheault, Nevada’s superintendent of public instruction, said he expects the Silver State’s identification formula to be a combination of factors, including test scores and special student populations.

Other candidates will be schools that have been identified as in need of improvement for at least five years in a row under the federal No Child Left Behind law.

Clark County Schools Superintendent Walt Rulffes said he will meet Thursday with his counterparts from the state’s other 16 districts to discuss the new grant program. One concern is that “turnaround” funding might be available only for a year or two, Rulffes said. Given the state’s shaky economic status, asking the Legislature to take over the burden of paying for new initiatives isn’t realistic, he said.

Walt Rulffes

He also said it’s too soon to speculate as to which Clark County campuses might be candidates for the “turnaround” grants.

However, there are a few campuses serving West Las Vegas students that appear to fit the preliminary criteria, having both long-standing low achievement and Title I status — several “Prime Six” elementary schools that have been the focus of intense scrutiny in recent weeks. Test scores for students at most of the Prime Six schools are well below the districtwide average. Nearly all students at the Prime Six schools are black or Hispanic, and all qualify for free or reduced-price meals.

As Nevada begins considering how to identify the schools most in need of a new direction, test scores should be one of the key measures, says Daria Hall, director of K-12 policy for the Education Trust, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group and think tank. However, multiple years of data need to be studied for evidence of improvement or growth. Schools that have stagnated or failed to make gains despite numerous interventions must receive special attention.

Those challenges are going to be difficult in states such as Nevada, where stimulus dollars have gone to plug massive holes in the education budget.

“There’s a whole lot of pressure to use whatever funds come from the U.S. Education Department to bring things back to normal,” Hall said. “But we know normal isn’t good enough, and isn’t serving low-income students and students of color the way they need to be served. There needs to be the political will and pressure from parents to say ‘No’ to more of the same. We need people to have the guts to say, ‘We’re taking this opportunity to make the hard choices, and do things differently for kids.’ ”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy