mrsunitedstates.com

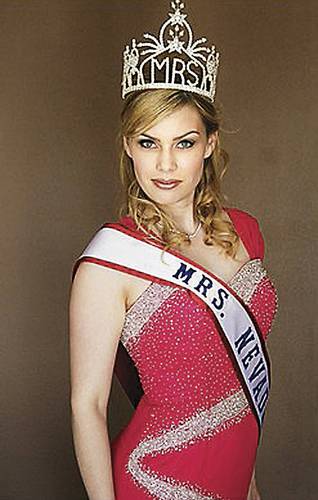

Juliette Kimoto’s photo from a pageant Web site.

Wednesday, Sept. 9, 2009 | 2 a.m.

Sun Archives

Beyond the Sun

Juliette Kimoto was crowned Mrs. Nevada in 2006. Her spouse, Kyle, also took home an award: Husband of the Year.

They were a happy, church-going couple with six kids, smiling on stage, accepting their beauty pageant awards.

They were also a couple in deep trouble with the law, and falling deeper by fathoms.

Federal authorities consider Kyle Kimoto the chief architect of an international telemarketing scam that duped roughly 300,000 Americans out of $43 million. When he won Husband of the Year, he owed the government $105 million in court judgments for the crime.

Three years later, Juliette Kimoto was sued by the Federal Trade Commission, the same agency that took down her husband, for large-scale fraud. In their July complaint, FTC attorneys alleged that Juliette was one of five Nevadans behind sham Web sites that promised consumers help getting government grants — sites that paraded stimulus funding like some kind of fiscal buffet: “With billions more on the way, it’s time to get your cut!”

Kyle Kimoto is serving a 29-year federal prison sentence. Juliette is awaiting her own trial. The couple have been convicted and accused, respectively, of different schemes that operate on the same principle: Tap into the fears of desperate people, or the needs of the naive, and you can sell anybody just about anything.

And there’s a lot of fear to tap into. The case against Juliette and her alleged co-conspirators is part of “Operation Short Change” — the FTC’s name for a crackdown on con artists using the bad economy against its victims: get-rich-quick schemes, bogus debt-reduction, phony jobs and, in Mrs. Nevada’s case, Web sites promising government grants alongside photos of President Barack Obama and rippling American flags.

“Scammers use current events to adapt their pitches, and scammers these days are exploiting a vague knowledge that there’s been this injection of stimulus funds into the economy,” said Karen Hobbs, an FTC staff attorney who coordinated Operation Short Change. “It’s very destructive. People struggling to make ends meet are more susceptible in a down economy.”

It’s unclear how many people may have been duped by the grant sites, though it’s believed the business generated millions in fraudulent revenue using a model that was pretty simple.

Visitors to the Web sites were asked to pay a small fee in exchange for assistance in obtaining grants. The fee was small compared with the money people claimed they made in breathless online testimonials: “It’s just so easy! I got my first grant for $330,000! All I have to do is search and click!”

But there are few, if any, federal grants for individuals or profit-making businesses. And getting government money is a complex process, not a point-and-click bonanza. So instead of help, people really got a “worthless computer program ... that does not actually help consumers obtain a grant,” according to the FTC.

More important, people who paid for grant help were also enrolled in additional programs, such as identity theft protection or legal services, all with recurring “membership” fees that could exceed $70 a month, according to court documents — the costly catch.

Because the additional programs and monthly charges were buried behind small-print online disclosures, people found out about the fees after they were deducted, the lawsuit alleges — after a tidy profit had been made.

It should be said that the case against Juliette Kimoto is hardly won. It should also be said that Juliette was one of five people with at least seven corporations among them accused of collectively running the scam — FTC lawyers are suing the lot.

Juliette Kimoto’s attorney declined to speak to the Sun.

And while Kimoto’s husband, her pageant title and her proclamations of religious piety make her stand out, she isn’t the only person with ties to prior scams.

One of her co-defendants, Steven Henriksen, is no stranger to the FTC. His brother, Michael Henriksen, was chief financial officer of Kyle Kimoto’s fraudulent telemarketing company. When the government started seizing Kyle’s assets in 2003, the court found Steven Henriksen was helping Kimoto move considerable sums of money. Moreover, the FTC believes Steven Henriksen is related to another defendant named in Juliette Kimoto’s case: Rachael Cook.

But the real overlap between each Kimoto case is the method: Both husband and wife are accused of using a fast-food approach to fraud — get lots of suckers to pay just a little bit. Instead of grants, however, Kyle made multiple millions hawking credit cards.

At his peak, Kyle Kimoto had telemarketers in call centers from Utah to India working for him. These telemarketers were calling people who had been denied credit cards, informing them they had suddenly been approved for a MasterCard, so long as they paid a pricey processing fee.

Preposterous as it sounds, federal prosecutors say 300,000 people paid and waited for their cards to arrive. Denied legitimate credit cards because of financial straits or histories of poor money management, they were soft targets.

Instead of getting credit cards, they got applications for a kind of debit card that had to be loaded with money to be used.

Kimoto’s telemarketers are estimated to have made more than 12 million calls. Five days before jurors convicted Kimoto, it appears his wife used a free online service to issue a kind of news release.

The release opens: “My name is Juliette Kimoto and I was recently crowned Mrs. Nevada.” It goes on to describe the pageant winner as an “ideal citizen” who owes her success to the Mormon church:

“Growing up in the church I learned the importance of serving others ... How blessed are we?”

Bank records show there were large cash transfers between Juliette Kimoto and grant case co-defendants starting in October 2008, one month after Kyle was found guilty. It’s not clear when the grant sites were launched, so it’s difficult to determine whether Kyle Kimoto helped build them or if they were created after he was sentenced.

Attorneys allege Juliette Kimoto used at least $30,000 in revenue from the grant scheme to pay for jury consulting in her husband’s case — the implication being that one fraud fed another.

Juliette Kimoto didn’t return the Sun’s calls for comment, and her attorney indicated she wouldn’t anytime soon.

The courts have shut down the grant Web sites until a still-unscheduled trial. Try to find them online, and you won’t get far. Search for Juliette, however, and you’ll find her 2006 pageant portrait floating around: sash, crown, evening gown.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy