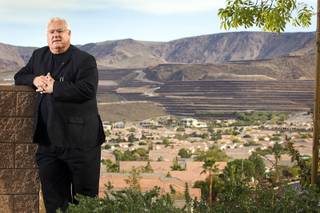

Architect Robert Fielden stands by homes at the Mountains Edge master-planned community December 9, 2010.

Sunday, Dec. 19, 2010 | 2:01 a.m.

Sun archives

- An early chapter in Vegas architecture (3-26-2009)

- Gehry’s design elevates awareness of Alzheimer’s disease, research (2-17-2009)

- In varied Vegas, two buildings spark architectural debate (5-25-2008)

- Renowned architect will design Alzheimer’s center (3-2-2008)

- Arts center to mix it up (10-24-2007)

- John Katsilometes gets Frank Gehry’s succinct opinion of architecture in Las Vegas (12-14-2006)

Robert Fielden, who moved to Las Vegas to be an architect in 1964, isn’t bitter about what has happened to his city. For the most part, when he passes the half-finished eyesores and fully finished absurdities that dot the landscape, he points and gives a hearty laugh that comes from his West Texas belly.

Fielden spent years, decades really, as a Cassandra and an iconoclast, warning that the boom was not sustainable and would end in disaster. He was largely correct. And yet, he still loves his city. “I wouldn’t trade it for anyplace in the world,” he says.

Now, though, gazing up at the Ascaya project, Fielden looks more besmirched than his usual bemused self.

A Hong Kong developer has blasted the once scenic Henderson mountains to create luxury home sites, although there’s no building going on, and the developer says there are no immediate plans to begin selling lots.

Fielden likens it to an empty mining camp.

“It’s just a shame. Ruined those beautiful mountains,” he says. “Puts tears in my eyes.”

Fielden’s metaphor, the mining camp, is more than visual.

He’s also conveying the consequences of the boom and bust for the entire valley: Once the mine has been depleted, and the company takes its money and packs up and leaves, the scarred landscape is forever changed. In the same manner, although the building boom is finished and the developers have mostly departed or gone bust, they left behind a landscape that will define our city for decades.

To understand the ways in which the bubble and its bursting will shape how we live for years, the Sun took a tour of the valley with Fielden and later with Eric Strain, another contrarian architect who has a history of asking the tough questions about why Las Vegas looks the way it does.

...

As it happens, the best view of Ascaya, that Henderson hillside, is from a vast parking lot behind an empty commercial development, one built with the expectation that growth would drive demand for new shops. The parking is in the rear, presumably to give the front of the shops a more urban feel. But it’s a pointless, faux urbanism — most everyone will have driven to get here, and it’s set far off the road.

Jeff Roberts of the firm Lucchesi Galati, which designed Springs Preserve, questions the wisdom of this urban style of development in suburbia. “The idea is that you drive to suburbia to get an urban feel — which is really weird,” he says.

There’s nothing urban about this parking lot near Green Valley Parkway and Horizon Ridge. Because of rigorous parking requirements — even, bizarrely, at taverns — we only use about a quarter of our commercial space. The rest goes to “free” parking. But as UCLA economist Donald Shoup points out in “The High Cost of Free Parking,” it’s not free at all. It merely raises the cost because the developer has to buy additional land, which means higher rents and higher prices for goods and services. The ample parking, meanwhile, inhibits any chance for actual urban spaces because walking across them is dangerous and unpleasant.

From this view, Fielden looks down at the homes in the valley below. For these homeowners — many of whom no doubt owe more on their mortgages than their homes are worth — the views of those mountains have been changed forever by the stalled Ascaya project.

“The land of a hundred thousand rooftops that all look alike — is it not?” Fielden marvels. “You’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. But everybody has a palm tree that does nothing but absorb water and gives you no shade.”

For both Fielden and Strain, this is a constant theme: The failure to understand the desert, its ecosystem, its light and heat. The failure to live with respect for the community and the natural surroundings. A blindness to context.

...

Context. Now we’re on Gibson Road in Henderson, up the hill from Interstate 215, and there sits Vantage, a boxy, glassy modernist condo development; a historical artifact of the era of the credit boom, and, perhaps, delusional exuberance. It was a $160 million project, but no one lives there. It sits on the hill, surrounded by suburbia, like a hipster who’s stumbled into a church that he thought was a nightclub.

Fielden acknowledges the downturn in the market probably killed Vantage, but then he asks, in a tone of jocular incredulity that he’s mastered, “When you look at that, does that give you a sense of value, a sense of home?”

He’s on a rant about a pet peeve. “Where does the sun track?” He gestures with his hand. “Look at all that glass. Exposed.” Only the north side of the structure will be spared the brutal sun. “East side. West side. South side. Glass!” Laughter.

Now we’re on I-215, the great beltway on the outskirts of town with its redundant commercial and retail blending together, gliding by. “And on and on and on,” Fielden says.

...

Architects say the Las Vegas real estate bubble had wildly distorting effects on the behavior of developers, architects, consumers and elected officials. “Everything was moving so fast, no one stopped to think about what they were doing,” Fielden says.

The mania for land and the hyperinflation of construction costs set off an economic sickness in which what seemed rational at the time, in hindsight, looks like folly.

This manifested itself in many ways.

• It seemed any project, no matter how preposterous, could make money. Thus, Vantage. Any number of condo and hotel projects on the Strip could also fit in this category.

• Rampant overbuilding. Those with land felt the need to build, and build now, and build with the highest possible density. They built with the assumption that growth in the valley — of residents, tourists, consumers — would lead to profitability. But the building continued even after the growth stopped and everyone ran out of money, both on the Strip and in the community. That has left us with the overhang that plagues the local economy.

• Foolish consumers. Investors thought they could make a quick buck, while families who merely wanted to own a home thought they had to buy now, lest they be left out in the cold. They were like people in a food line who gorged themselves on whatever the developers fed them, fearing this was the last meal, or fearing that the next meal would be unaffordable. So they ate and ate and ate, and then borrowed more money to keep eating, until they got sick.

• Elected officials, who loved the ever-growing tax revenue and the bottomless bag of campaign donations from developers, were usually quick to approve even harmful development. For instance, they allowed subdivisions with housing density to match major East Coast cities, but without any of the amenities of urban density.

...

We drive west and then north on I-215 and stand looking at the half-finished Shops at Summerlin Centre, which halted construction in 2008, suspending 1 million square feet of retail, office and condominiums in an “urban village” atmosphere. Now, it’s like a massive, wildly overpriced avant-garde sculpture of steel and concrete.

It’s not clear when it will be finished, especially since a smaller but similar development, Tivoli Village at Queens-ridge — yes, actual name — seems set to open nearby next year.

Fielden says Summerlin Centre, with its mixed-use plan, may have been worth doing, but only after the developer could show true demand for it. He laments the constant pattern, enabled by failed growth policies and myopic public officials, wherein a shiny new mall goes in, which cannibalizes a different mall, simply moving value from one place to another. In the end, we wound up with retail vacancy rates, for instance, of more than 10 percent.

...

We drive east on 215 to ManhattanWest on Russell Road, another half-finished mixed-use development. Dense, high-rise urbanism plopped down in the suburbs, its name a great irony. Some windows are covered with plywood, like an abandoned property in a city that suffered a natural disaster.

It’s like a Hollywood set. But of what? It imagines that it’s supposed to look this way because somewhere, there’s something that’s cool and authentic and looks like this, perhaps? But there is no such place. This cardboard, Potemkin-village effect is only exacerbated by the surroundings.

Across one abandoned road is a self-storage joint. On Russell are some apartments, run-of-the-mill valley multifamily housing, albeit a bit nicer and newer than most. Fielden is unimpressed. “Mundane. Pragmatic. Pretty boring. Dull, ugly places to live.”

More than once Fielden will compare various residential developments to the kinds of barracks the military might build for its officers. He served in the Marine Corps, so he’d know.

As we pull away from ManhattanWest, we pass an empty lot with a sign: “FDIC owned property. No trespassing.”

...

We drive south on Fort Apache Road to something called Woodscape Parkway, where the backs of houses, one just like the other, seem to taunt Fielden. “It’s mundane and ugly. It looks like a third-grade drawing.”

Inside the development, the front of the houses have some variety, but Fielden points to unfortunate elements. The street is strangely wide given the scale of the small homes, and there are no sidewalks. This will cause drivers to go faster, which will force parents to keep children from using the street for play. Then there’s the faux porches, which are meant to replicate a common feature of homes in the South or East, a place where families and neighbors swap gossip and tell tales. But these porches aren’t big enough for a single chair. “It’s decoration. They’re selling you something you’re not receiving,” Fielden says. In short, aside from a small grassy common area, the design elements encourage people to stay inside.

Now we’re in the southwest valley, at the edge of an archipelago of development — subdivisions sometimes surrounded by empty lots, also called leapfrog development. We’re standing outside a complex filled with three-story single-family homes that Fielden approximates are a mere 6 feet 8 inches apart. Magic Johnson couldn’t lie down between them. And yet, just over the obligatory concrete wall sits a half-finished road and fields of rocky desert debris. The people live on top of one another, but still, they have to go to their garages and hop in their cars to do anything.

Roberts says this was typical. “We’re going to build all these and make these promises, sell houses and turn a profit, and eventually someone will deliver services.” Living in Southern Highlands, however, he waited years for a grocery store.

...

Allowing this kind of sprawl was a mistake we will feel for years, Fielden thinks.

How did it happen? With dollar signs in its eyes, the community invited outside developers, the companies that made billions of dollars on tract homes in Southern California and Phoenix. And what did they bring? Southern California and Phoenix. And they relied on the same business model: cheap land and the mass production of homes, but in a sharply limited variety of models.

Even for fans of Southern California, there was a downside. As Fielden and other Las Vegas architects point out, in Orange County, the houses face west, for gentle sunsets over the Pacific. As for faux Tuscany, it makes some sense in California, which is similar in many respects to the Mediterranean.

But here? The Western sun is the enemy. And the faux Tuscany here can allow heat to gather and leach into homes. But that has rarely been a consideration to developers.

Did it work in California? Then do it here. Like McDonald’s, or Wal-Mart.

Reed Kroloff, an architect who is director of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and the former editor-in-chief of Architecture Magazine, says it’s almost foolish to think developers would do anything but replicate the winning formula, which made them so much money in the rest of the Sun Belt. Given their capital outlays for land and materials, the companies, many of which are eyed closely by shareholders, are extremely risk averse. “They don’t take chances.”

“When they figured out how to sell Irvine Ranch,” Kroloff says, referring to the master-planned suburban community in Southern California, “they were going to do it again” in Las Vegas. Their position was merely reinforced by federally backed lending polices, federally built roads, and zoning policies they nudged into being. “It’s a circle, and a tight one, and a hard one to find your way out of.”

Fielden is reminded of the Malvina Reynolds song, the theme of the TV show “Weeds”:

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes made of ticky tack,

Little boxes on the hillside,

Little boxes all the same.

...

After growing up here, Eric Strain left to study architecture at the University of Utah and wound up breaking a promise he made never to return to “this hellhole,” he says, half-joking. He came back in 1991 and started a boutique firm in 1997. Strain’s firm, assemblageSTUDIO, has designed striking modernist homes at the Ridges in Summerlin, Border Grill, as well as the student services and early childhood education buildings at UNLV.

We’re at a Mexican place near his office, an appealing loft space that also has the feel of a graduate school apartment with renderings and empty wine glasses, in a gritty part of downtown. He tells an anecdote to properly sum up the building boom and what it wrought: He and about 50 others in the building community took a bus to Phoenix to see projects there. Suddenly someone at the back of the bus, with much commotion, yelled out, “We just passed my street! That’s my house!” Even the street name was the same in Phoenix as in Las Vegas. Think of it this way: Every cup of Starbucks coffee in Las Vegas tastes just like the one Phoenix.

Another time, he picked up some friends at the airport, and as they drove into his development, the friends’ 7- or 8-year-old daughter blurted out, “Eric, how do you know which house is yours?”

Strain, though, is insistently hopeful that the mania has passed and Las Vegas can become its more authentic self, one more integrated and respectful of its natural environment, building an original aesthetic cultivated here rather than by “star” outsiders. (How needy were many builders for status? Strain was once told he could get more work in Las Vegas if he simply moved his firm to L.A. or New York.)

One outsider, one star, who has given us a significant building, Strain thinks, is Frank Gehry, calling his Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health building an important milestone for its civic and aesthetic provocation.

“You can like or not like his building, but you know it. If everything that was created and everything we built, everybody loved, it would just be more of the same,” he says. “And I think that’s where, in the good times, we got into such a rut, so that if it looked liked the one next door, then it was good.”

He points to the sameness of schools and firehouses with frustration — buildings that might have helped define a neighborhood and give it a sense of place, and for not very much money. (One School District official told him the only priority was “butts in seats.”)

“I don’t think we want to live in Disneyland,” he says, although it’s not clear if the populace would agree.

In the same vein of supporting diversity, Strain seems hopeful about CityCenter and its future.

Despite grandiose claims, it isn’t clear that CityCenter has transformed Las Vegas in any meaningful way. As Paul Goldberger put it in The New Yorker, “CityCenter certainly fails to live up to the claim implicit in its name — the hope that it is going to give Las Vegas, the place of ultimate sprawl, a genuine urban focus. As urban planning, it doesn’t go much farther than Caesars Palace.” Meaning, it pays fealty to the automobile. He concludes, CityCenter “isn’t much of a center, or much of a city.”

Roberts is not as dismissive. Although conceding that its scale makes it hard to identify it as urban in any traditional sense, he applauds the integration of art and sculpture and emphasizes it feels truly different from the rest of the Strip, which has a single-minded obsession with revenue-maximizing rooms, casino floor and nightclub. Fielden, whose firm designed the Stardust, Desert Inn and Tropicana, puts it this way: “How many bails of hay can you fit in a barn?”

Strain says many urban spaces often take years to change and evolve and meet their potential. Downtown Los Angeles has experienced this in the past decade. He expresses some confidence this will happen at CityCenter.

He shares a similar hope about UNLV, although as we drive there to walk through the campus, he expresses his frustration. It’s a young university, badly in need of private donations, and in that quest successive administrations became far too deferential to big donors and their desires, which often weren’t aligned with the interests of the university or its students, Strain says.

“It’s tough to put your finger on what’s missing, but something is missing,” he says, on the campus of UNLV. Amid all the visual noise and insistent anti-intellectualism of Las Vegas, UNLV would ideally serve as an oasis of contemplation and dialogue, but also dialogue with the rest of the city.

In one of the main quads, Wright Hall, the Student Union, the Business School and the Humanities Building, each representing wildly divergent looks, combine to make a soup of dissonant ingredients.

“If the buildings don’t tie together, then the landscaping should tie them together,” he says. But it doesn’t. Often, in deference to the automobile, the buildings’ main entrances are toward the parking lots.

Long stretches on campus have nowhere to sit. And although it may seem like nothing, Strain’s question is quite trenchant for a college campus: “Where do you throw a Frisbee?”

Strain admires Lied Library, its use of materials and an interior space he calls “wonderful.”

But the library opens on to another quad that some paving contractor made a fortune on because it’s all concrete. “This, this is hideous. It’s like a runway. I’m surprised planes haven’t mistaken it for McCarran.”

He looks at this corridor of failure, and although he’s referring to this space, he’s also talking about the city: “Nobody looks at the potential of what could be. We just accept what is.”

We’re back in downtown Las Vegas at an affordable housing complex at 211 N. Eighth St., a project designed by San Diego architect Rob Quigley. For Strain, it shows what architecture can do up and down the socioeconomic ladder. Outdoor circulation areas are wrapped in a playful blue netting that provides air flow. The windows are protected from sun by chevrons, although natural light will still penetrate the windows. (Unlike so many others, Quigley adapted his building to the desert.)

“It shows we don’t need to treat people who need affordable housing to bad architecture, to put them in boxes,” Strain says. In San Diego, Quigley achieved some recognition for these projects. Here, his project, completed around 2000, went unnoticed; at the time, everyone had the mania.

...

So the real question is: What now?

The architects are largely in agreement: We need to grapple with what we’ve done, learn from mistakes, and begin planning a new future, with the entire community playing a role.

Despite what’s happened, they are cheerful, optimistic even, that a new future can be had. Strain says if he had a pocketful of money, he’d be building. It’s time, he says.

Many of the out-of-town developers, the Tuscany crowd, have left. But these architects are still here.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy