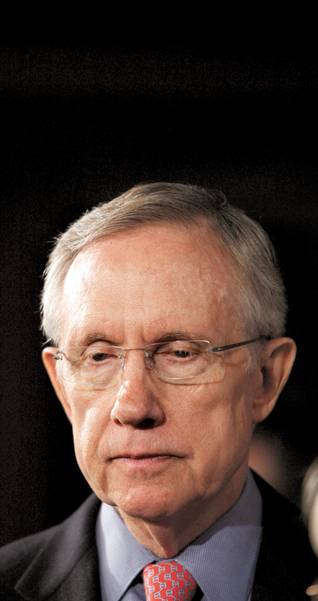

Pablo Martinez Monsivais / associated press

Even rank-and-file Democrats turned against the “Cornhusker kickback” Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., brokered. “If you’re a rainmaker, you get blamed for the flood. What makes you a hero one day in American politics casts you into darkness the next,” said Ross Baker, a congressional scholar at Rutgers University on challenges Reid faces as leader.

Sunday, Jan. 31, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Sun Coverage

Once the derisive nickname emerged — the “Cornhusker kickback” — it was all over.

The deal that Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid cut for Nebraska Sen. Ben Nelson to secure his vote on the massive health care reform bill had barely come to light before it was shot down in infamy.

Even Nelson, the conservative Nebraska Democrat, said he never intended to get a special deal. All he wanted was to ensure that all states got some relief from the proposed Medicaid expansion in the health care bill. When the legislation came out with only Nebraska’s name on it, he said he was as surprised as anyone.

By then it hardly mattered. A month later Republican Scott Brown was headed for victory in the Massachusetts special Senate election — scoring points with voters by railing against Washington’s backroom deals.

The swift rise and fall of the Cornhusker kickback brings into sharp relief a contradiction in American politics: We want our elected officials to be powerful purveyors of special deals — people who can bring home the bacon— but not too powerful that they appear unseemly.

Perception, perception

Reid, arguably Nevada’s most powerful senator in history, faces a difficult re-election campaign and a double-edged attack over his clout in Washington.

On one hand Reid is blamed by his opponents for not doing enough to help Nevada — not putting his thumb on the federal spending scale to the state’s advantage. On the other, when Reid cuts the deals that are the lifeblood of politics — either for Nevada or to secure votes for President Barack Obama’s agenda — the same opponents criticize the moves as shady political behavior.

Ross Baker, a congressional scholar at Rutgers University, said Reid faces a dilemma common to politicians in leadership positions.

“If you’re a rainmaker, you get blamed for the flood,” Baker said. “What makes you a hero one day in American politics casts you into darkness the next.”

Nevadans have a complicated relationship with Reid’s power in Washington. The state’s stubborn independent streak makes it uneasy with Washington’s largesse. Nevadans do not like taxes and prefer to see themselves as the types who can do just fine without government aid, thank you very much. It’s part of a libertarian ethos going back to the state’s beginnings.

That independent self-image, however, isn’t a completely accurate one. Like most Americans, Nevadans have relied heavily on government — to provide cheap land for mining, dam the Colorado River, build and maintain the state’s vast highways and provide Medicare and Social Security.

But when Nevadans see other states faring better in Washington, particularly when times are bad in the Silver State as they are now, they complain that they are not getting their cut.

Sue Lowden, the former state Republican Party leader seeking to unseat Reid this fall, offered a real-time example of Nevada’s desire to have it both ways. In a comment aimed at Reid, she said “taking more of our private sector dollars during a recession to grow government does not work.”

Yet a week later she complained that federal stimulus money was going for a train in Florida instead of one in Nevada. (One Nevada train project did not request such funding because it is a private venture; the other did not have the state’s approval to apply.)

‘Sweeten the pot’

Reid is a master of the inside deal.

“Legislation is the art of compromise,” he likes to say. Translation: Bills cannot pass unless you find out what a lawmaker needs.

“You need a majority,” Baker explained. “Some people are going to join you because they believe in the policy. Other people are going to need inducements. So you sweeten the pot.”

This is the so-called sausage making, often unseen by the public, required to create legislation.

During the crafting of the Senate health care bill, it was no secret that Nelson, the Nebraska senator, was holed up in Reid’s office in the final December hours of debate. On three days in a row, Nelson made his way to Reid’s second floor office in the Capitol.

It became clear what he was after. The conservative Nebraskan wanted to remove the public option from the bill and tighten restrictions on abortion. He had other requests, but his interest in getting full, permanent federal funding for Medicaid for his state — what would be known as the Cornhusker kickback — was “far down” on that list, Nelson said.

“It was not a deal maker, not a deal breaker,” Nelson said last week. “I’ve been like the dog chasing the car ever since.”

Fallout of the deal

But Nelson should have recognized the potential for controversy.

Reid had secured a similar full-funding provision for Nevada in an earlier version of the bill — one that would provide Nevada and a few other states hit hard by the recession with 100 percent funding for expanded Medicaid programs for the first five years of health care reform.

Reid’s deal for Nevada raised eyebrows — before it was extended to all states in more limited form. In the final version, all states would receive full funding for the first three years of health reform.

(Reid also secured for Nevada the largest single percentage increase in the Medicaid funding formula in the stimulus bill that passed earlier in 2009 — a behind-the-scenes Reid deal that got less notice.)

After a marathon Friday session, Nelson and Reid struck a deal and sealed it with a handshake.

The next morning Nelson announced he would vote for the health care legislation.

Almost immediately, the Cornhusker kickback was the joke making the rounds. Even Democrats scoffed. It joined Reid’s previous deal to secure the vote of Sen. Mary Landrieu of Louisiana — aka, the Louisiana Purchase.

Reid defended it.

“There’s 100 senators here. I don’t know if there’s a senator that doesn’t have something in this bill that’s important to them,” Reid said. “If they don’t have something in it that’s important to them, it doesn’t speak well of them. That’s what legislation is all about — it’s the art of compromise.”

But his explanation did nothing to quell the outrage over the Cornhusker kickback.

Taking a page from Brown’s book, Nevada Republicans attacked the deal as an example of Reid’s power gone awry, and out of step with voters.

“Harry Reid thought it was business as usual,” said Chris Comfort, executive director of the Nevada state Republican Party, after the Republican victory in Massachusetts.

In an open letter to Reid, Republican Senate candidate Danny Tarkanian said “the ‘Cornhusker Kickback’ is a perfect example of your leadership position compromising — not benefiting — your ability to help the people of Nevada.”

Last week, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi singled out the deal as one provision that would have to go if the House and Senate health care bills were to be reconciled. “Policy shouldn’t be made on the basis of one senator,” Pelosi said.

Rank-and-file Democrats didn’t want to be associated with the deal.

“It hurt us,” said Rep. Gerald Connolly, the first-term Democrat from Virginia, who is president of his freshman class.

But it is easy to oppose pork when it is not your own. Asked if this latest episode would be the end of deal making in Congress, Connolly smiled and reinterpreted a famous line from “Casablanca”: “We’re shocked, shocked, deal making is going on to try to get to a final product.”

Connolly added: “That’s how great pieces of legislation get passed. Listen to the (President Lyndon) Johnson tapes during the debate on Medicare. We wouldn’t have Medicare if he didn’t do some of that log rolling.”

Reid’s backroom style is old-school in an era when the president has promised a transparent White House. But Reid unapologetically presses on, securing deals — some for Nevada, others to advance the president’s agenda.

“President Obama breathes the clean, pure air of the White House, and Congress is different. It has always been different,” Baker said.

“Each bill is going to involve awarding little side benefits. It happens every day. Democrats and Republicans do it. Liberals and conservatives do it. It would be a very, very nice and nobler process if everybody voted according to high principle.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy