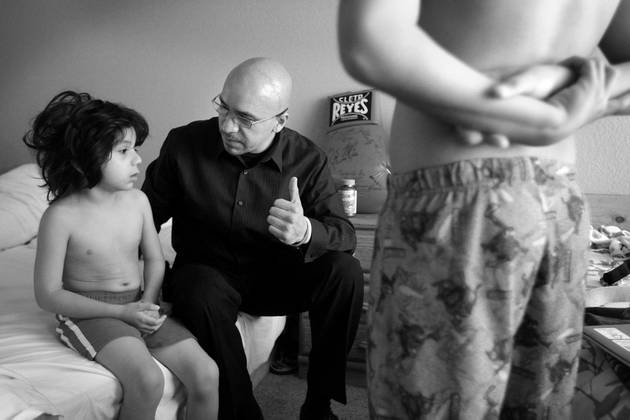

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez is consoled by his family and friends Aug. 27, 2012, after attending a Bryan Clay hearing at the Regional Justice Center in Las Vegas. Clay is the accused killer of Martinez-Sanchez’s wife and daughter.

The boys’ refuge; the father’s hell

It’s the first day of school and Arturo Martinez-Sanchez is anxious. Until today, he hasn’t had to face the morning routine as a single father, and he can’t find something.

He is opening and closing cabinets and peering into the back reaches of drawers. Finally, there it is: the blender lid. Crisis No. 1 averted. He can mix the shake, made of sliced apples, oatmeal, chocolate and two eggs.

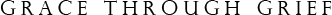

Arturo has given himself plenty of time this morning. He awoke an hour earlier, showered and dressed in black slacks, a collared shirt, a belt and dress shoes.

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez prepares breakfast for Alejandro and Cristopher on the boys' first day of school Aug. 27, 2012.

Physically, he’s ready for the day. Emotionally, maybe not so much.

He’ll watch his youngest, 5-year-old Alejandro, start kindergarten and his middle child, Cristopher, 10, enter fifth grade.

Then he will head to the courthouse and face the man who allegedly raped and killed his wife and daughter.

•••

Arturo heads to the bedroom he shares with his two boys in his sister and brother-in-law’s house. It’s time to settle an age-old question on the first day of school.

“Which one do you want?” Arturo asks Alejandro, holding up two T-shirts.

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez wakes Alejandro, left, 5, and Cristopher, 10, on the boys' first day of school Aug. 27, 2012.

“This,” Alejandro says, smiling sheepishly, pointing to a “Cars” shirt.

Arturo ties Alejandro’s shoes, then inspects his son from head to toe. Alejandro’s black shorts don’t cut it. They’re falling off his skinny frame. Off go his shoes. Arturo rifles through a stack of clothes, snags a tiny pair of blue jeans and hurriedly slides them on Alejandro.

“Ah, perfect,” he says.

So far so good as Arturo warms up to the morning drill. The summer months slid by in a chaotic blur of doctor appointments, physical therapy and small victories amid grief. He regained his driver’s license. He reopened his boxing gym. He publicly forgave Bryan Clay, the suspect. And, slowly but surely, his speech is coming back.

Alejandro Martinez, 5, gets his last few minutes of sleep before his first day of kindergarten in Las Vegas on Aug. 27, 2012.

A gold-framed photo of 10-year-old Karla and Yadira, his wife of 14 years, rests on a bedside table. Paper wreaths from their funeral — adorned with messages of love — hang across the room. The decor reminds Arturo and his boys of all they have lost. Karla should be entering middle school and Yady should be making the clothing choices.

In the adjacent bathroom, Arturo glides a comb through Alejandro’s knotted hair as the youngster whimpers in pain.

“Stay strong, OK?” Arturo says.

“And don’t say poopie face to the kids,” Cristopher chimes in, thinking the conversation has turned to school.

It’s almost time to go as the boys head to the kitchen for their shakes. Cristopher gulps his down, eager to be on his way to school and friends; Alejandro protests and only takes small sips when Arturo holds the glass up to his mouth.

Cristopher Martinez, right, 10, straps his brother, Alejandro, 5, into a car seat, getting ready to head out for the first day of school Aug. 27, 2012.

“Take it — one, two three,” Arturo says. “Drink it, please.

“More ... more ... more ...”

Arturo’s sister, Gaudia Martinez-Seal, appears in the kitchen. Her son, Jesus, started his first day of high school. Before he left, he hung a Post-it note on the boys’ bedroom door, wishing them good luck.

Gaudia hugs her nephews and traces the sign of the cross over them. With that, Arturo ushers them to the car. As they back out of the driveway, Cristopher turns up the radio for the Neon Trees’ latest pop song.

Summer is over.

•••

"This is your school,” Alejandro tells Cristopher as they pull into a gravel parking lot next to Mabel Hoggard Elementary School.

“It’s your school now, too,” Cristopher says back.

For Cristopher, the elementary school is a place of familiarity, the reason he wanted to return. It was his choice and Arturo approved. Now was not the time for more change.

“Cristopher, how are you, dude?” a staff member calls out as the boys and Arturo make their way to the entrance.

It’s a mob scene outside the school as many parents forgo the drop-off and instead accompany their children into the school’s open-air courtyard.

Alejandro, distracted by the scene and first-day jitters, runs head-first into a pole. Tears well in his eyes.

First stop: the nurse’s office.

“You’ll be fine,” Arturo tells Alejandro as a nurse tends to the emerging red bump above his right eye.

Cristopher takes one look at his brother’s injury and shrieks, “Oh my gosh!”

Arturo again consoles Alejandro, whose tears are drying up as he sits, still wearing his backpack.

“Hate to see your baby go to school?” a nurse inquires.

“Yeah,” Arturo says, then sighs.

“They’ll be fine. We’ll take good care of them,” the nurse says.

Cristopher Martinez, left, 10, and his brother, Alejandro, 5, head out to line up with their classes on the first day of school at Mabel Hoggard Elementary School in Las Vegas on Aug. 27, 2012.

Outside again, Cristopher holds his younger brother’s hand as they walk to the playground, where Arturo tells Cristopher goodbye. Cristopher’s teacher will be Miss Maher, a teacher new to the school who, staff members assure Arturo, will be a good fit.

The playground is a scene of frenzied excitement as older children reconnect with friends, see old teachers and meet new ones. In the kindergarten corridor, trepidation might be a better word — for both the students and parents.

As Arturo and Alejandro round the corner, a line of kindergartners is entering Mr. Hernandez’s classroom. Several are crying as parents try to find the right words to boost their spirits.

Genaro Hernandez spots the father-son pair and steps forward.

“Hi, Alejandro! How are you?” he says.

Alejandro smiles but doesn’t speak.

Hernandez guides Alejandro to his seat at a six-student table while Arturo watches from near the door. Today will be about introductions, Hernandez says.

Alejandro turns his head and flashes his dad a thumbs-up sign — Arturo’s cue that, like it or not, it’s time to say goodbye.

Alejandro Martinez, 5, gives a thumbs-up to his dad during his first day of kindergarten at Mabel Hoggard Elementary School in Las Vegas Aug. 27, 2012.

“Basically, when they start studying, you’re losing them one cycle at a time,” Arturo says as he makes his way to the cafeteria for a parent meeting. “Kindergarten. Junior high. You start losing them.”

In the cafeteria, filled with other parents of kindergartners, Arturo spots a piano against a wall. He says Karla used to take lessons on it. He stares off into the distance as he recalls the accomplishments of his daughter — his “princess,” his “Karlita,” as he used to call her:

“She was a pianist.”

“She was a yellow belt.”

“She was first place in freestyle swimming.”

The president of the school’s Parent Teacher Student Association opens the meeting by touting the benefits of enrollment at Mabel Hoggard, a magnet school and home of the Challengers.

Principal Celese Rayford offers a small dose of reassurance to any parents struggling with the kindergarten milestone.

“We are a community,” she says. “Please know that as you are dropping your kids off, we are going to take excellent care of them.”

Arturo knows that. Karla and Cristopher grew up attending Mabel Hoggard, and it’s the place Cristopher sought help on that Monday morning in April four months ago.

School is the one certainty in the family’s life as it enters a new reality. What worries Arturo is providing for and raising two sons without their mother and sister.

Arturo contemplates it all as he walks back to his car.

“A lot of stuff goes through my mind,” he says. “I don’t know how I am going to handle the kids for the rest of their lives.”

And then it’s like he hears his own words to Alejandro about staying strong.

“I can deal with this,” he says to no one in particular.

Now it’s time to see the man indicted in the rape and murder of his wife and daughter.

•••

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez waits outside of court to attend a Bryan Clay hearing Aug. 27, 2012, at the Regional Justice Center in Las Vegas. Clay is the accused killer of Martinez-Sanchez's wife and daughter.

Arturo paces the 14th floor of the Regional Justice Center in downtown Las Vegas. He is joined by family and friends.

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez holds a cross before walking into court to watch as Bryan Clay appears for a hearing Aug. 27, 2012, at the Regional Justice Center in Las Vegas. Clay is the accused killer of Martinez-Sanchez's wife and daughter.

They huddle in the hallway as sunlight streams through large windows, reminisce about old times and whisper with a victim advocate appointed by the court.

Arturo is mostly quiet, methodically rubbing a small metal cross that he then slips into the chest pocket of his suit.

The chatter dies as they enter the courtroom, filling two rows of public seating. Sitting just 15 feet in front of them, next to his court-appointed defense attorney, is Bryan Clay, the accused.

Arturo removes the cross from his pocket and grasps it as he eyes the 22-year-old man with short dreadlocks, an unshaven face and standard blue jail attire.

District Court Judge Jessie Walsh enters, breaking the moment and signaling the start of the hearing.

“Your honor,” begins Clay’s defense attorney, Anthony Sgro. “Essentially, Mr. Clay seeks to attack, I believe, four of the counts currently alleged in the indictment. One of them is the burglary charge and the others are the sexual assault charges.”

In June, a grand jury returned a six-page indictment charging Clay with 10 counts connected to his alleged crime spree that began a few blocks away from the Martinez-Sanchez house.

Separated from others in jail, Bryan Clay awaits trial

The first three charges — first-degree kidnapping, sexual assault and robbery — relate to the 50-year-old woman Clay allegedly followed, grabbed and forced into a vacant lot at the corner of Vegas and Tonopah drives.

The defense isn’t fighting the legal foundation of those charges.

But there is a fundamental legal issue involving the alleged rapes of Karla and Yady: Were they alive or dead when they were sexually assaulted?

During grand jury testimony, neither the sexual-assault nurse examiner nor the medical examiner pegged whether the sexual assaults occurred before or after each died.

Gaudia Martinez-Sanchez, the sister of Arturo Martinez-Sanchez, breaks down in court Aug. 27, 2012, while attending a Bryan Clay hearing at the Regional Justice Center in Las Vegas. Clay is the accused killer of Arturo Martinez-Sanchez's wife and daughter.

“Rape requires a live victim,” Sgro tells the judge, citing a 1996 Nevada Supreme Court decision. “If there is evidence of an assault and it is impossible to determine pre- or post-mortem, you don’t just charge the most serious crime,” he says.

Arturo and family shake their heads in silence.

Prosecutor Robert Daskas hands the judge a photograph from the crime scene. It’s graphic, he says, and no one else should have to see it.

“What’s significant is the evidence in the case clearly indicates both the mother and the 10-year-old daughter were attacked with a hammer — first the mother in her bed and then the daughter in her bed,” Daskas says. “They were both dragged to the floors of their respective bedrooms, where they were raped by the defendant.”

The blunt, step-by-step description of her niece's and sister-in-law’s deaths pains Gaudia. She buries her head in her hands.

Daskas continues: “Common sense tells us their hearts were still beating for that amount of blood to be present on the floor, where each of them was raped.”

After more back-and-forth between the attorneys, Walsh rules against the defense. All counts remain.

Arturo exits the courtroom visibly drained and numb, with the small, metal cross still within his grasp.

“I have no words,” he says.