Sam Morris / Las Vegas Sun

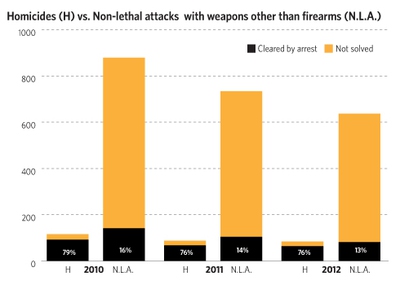

While his mother Angela looks on, Kaleb uses a toy thermometer to take his father Tom Cunningham’s temperature Saturday, March 30, 2013 while Tom recuperates from surgery after being stabbed in the stomach. Metro Police say about 84 percent of similar non-lethal attacks with weapons other than firearms are unsolved since 2010.

Wednesday, June 19, 2013 | 2 a.m.

J. Patrick Coolican

Sun archives

A few months ago, Tom Cunningham got into a brief argument with a man in a parked truck in one of the most run-down areas of Las Vegas, near the corner of Main Street and Washington Avenue.

Cunningham says he regrets it more than anything he’s ever done.

After walking away from the argument to get a “loosey” — a slang term for a single cigarette — at a convenience store, he returned to Main and Washington, just outside the Best Western where he was staying with his fiancee, Angela, and their 4-year-old son, Kaleb.

“I didn’t see or hear him until he was right up on me,” he says of the assailant. “By the time I turned, he was right up on me.”

The man stabbed Cunningham in the stomach.

The criminal had the same build as the man he had argued with, but Cunningham didn’t get a good look at the guy’s face.

“When you get stabbed like that, it happened so fast, I couldn't focus on anything else but the fact I got stabbed.”

Cunningham, 32, crumpled down and watched the blood pour out. He was rushed to University Medical Center, where he underwent four hours of surgery.

Doctors saved him, but he was left with a foot-long incision up his torso and a whole mess of painful complications. He could easily have been killed.

Metro Police have not made an arrest and have no information on potential suspects, spokesman Bill Cassell told me. It seems like a cold case almost from the get-go.

Unfortunately, the situation is all too common.

Since 2010, among the 2,250 nonlethal assaults with weapons other than firearms, such as knives, bats, bricks, etc., 1,924 remain unsolved. That’s 86 percent.

This mirrors similar data I reported this week on gun crime in Metro’s jurisdiction: 93 percent of nonlethal firearm assaults since 2010 remain unsolved.

The only good news is that the number of nonlethal assaults with weapons other than firearms has declined 28 percent, from 879 in 2010 to 637 last year.

Cassell says crimes like the Cunningham stabbing are difficult to solve, as close to a stone-cold whodunit as you’ll see. The victim did not know the perpetrator and could not give a description. There were no good witnesses. There was not much in the way of physical evidence, and the criminal took the weapon with him.

Budget cuts make solving these crimes even harder. In recent years, Metro has eliminated 506 positions: 238 officers, 236 civilians and 32 temporary positions.

Cunningham says Metro told him they visited him in the hospital but that he was so out of it from surgery that he doesn’t remember talking to them.

A couple of weeks or so later, a Metro detective and an evidence technician visited him at his motel room. Cunningham recalled for them that the man he argued with before the stabbing — and would seem to be the lead suspect — had been sitting in a truck that was parked in a driveway. Cunningham wonders if the people who live at the house where the truck was parked might know the owner of the truck. No doubt Metro pursued this lead and came up empty.

“It sucks this guy is gonna get away with it,” Cunningham says.

Cunningham and his young family were already struggling, teetering on the brink of homelessness, here in Las Vegas seeking help from family.

After the stabbing, they understandably developed a bad feeling for the place and have since moved to Indiana, where Cunningham works for a childhood friend’s small business.

While happy to be in a more stable and nurturing environment, Cunningham now suffers from chronic, daily abdominal pain that he can do little but try to ignore.

“It gets so bad certain days, I stay in bed all day. I can’t get out of bed. That’s two or three times per week. But I have to tough it out and make money to support the family.”

He has been to an emergency room several times since arriving in Indiana. He says he’s been the recipient of so many CT scans that doctors have put a moratorium on any more, worried about too much radiation.

He’s had kidney stones, pancreatitis, gastritis, all appearing since the stabbing.

Once his Medicaid application is approved, he’ll see a gastroenterologist to determine what, if anything, can be done.

Until then, he’s on a cocktail of drugs for pain, sleep and digestive troubles.

Like many people who suffer from chronic pain, he is depressed, but he is also anxious about providing for his family and future surgeries.

“I'm afraid they're going to have to cut me open again. And I don't want to be cut open again. I'm scared,” he says.

Cunningham says he tries to keep his struggles from his young family, but it’s impossible for them not to know: “I don't let them know what's going on with me. I don't want them to worry.

"But when I go to the hospital, of course they worry about me.”

Cunningham and his family are not the only victims here. His first UMC bill was more than $100,000. And he went to the UMC emergency room several times after his release because of severe pain, likely piling up thousands more in bills. Because Cunningham has no health insurance, UMC, the region’s only county-owned public hospital, will have to eat the cost. That means taxpayers will have to eat the cost.

More distressing than the money, however, is that for Cunningham and nearly 2,000 other victims of similar violence during the past three years, justice remains undone.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy