Pat Mulroy, general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, is shown during an editorial board meeting at the Las Vegas Sun offices in Henderson, Jan. 18, 2012.

Friday, Oct. 11, 2013 | 2 a.m.

For more

- For want of water

- Water Authority’s Pat Mulroy to retire

- For now, valley’s ‘water cops’ focused on education, not enforcement

- Proposal to hike water rates would pay off debt

- Lawsuits seek to block Nevada water pipeline

- More homeowners turning to artificial turf

- Environmental group, opposed to pipeline, suggests ways to solve Las Vegas water woes

- Customers flood Water District meeting with complaints about new rates

- Water Authority OKs rate hike, raising residents’ water bills

In the early months of the new century, life was good for Pat Mulroy.

A years-long and often contentious battle over Nevada’s right to excess water that roared down the Colorado River, through Lake Mead and into California, was nearing a resolution. Mulroy’s tenacious negotiating and relentless politicking, traits that would come to define her career, had her and all of Southern Nevada poised for a momentous victory that would allow the region a share of the river surplus and the fuel for continued growth.

“There was probably a four-month window in 2000 when I could have said: ‘OK. The world is wonderful. I’m putting on my rose-colored glasses and I’m done,’” Mulroy said. “I miss those four months.”

In the nine years since 1991, when she became general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, Mulroy already had made more progress raising the region’s stature among Colorado River players than any Las Vegas water official had in the previous 60 years.

But unknown to Mulroy and other water officials along the Colorado River, a drought of unprecedented severity was taking hold in the western United States.

“We were happily overusing the Colorado River in 2000 and 2001. I took a resource plan to the board that showed we had a reliable 50-year water supply and then ... whammo,” she said.

In 2002, snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains into the Colorado was down three-quarters from a typical year.

Mulroy’s agency launched ambitious plans that included paying residents to tear up their grass and accelerated a controversial plan to pump groundwater from rural Nevada counties to quench the thirst of Las Vegas and its economy.

After a decade fighting over Colorado River surpluses, the second half of Mulroy’s tenure at the water authority would come to be defined by potential shortages and the daring lengths she would go to secure water for Southern Nevada’s future.

The two halves of Mulroy's tenure, each fraught with challenges, serve as chapters of a story that has seen Mulroy vault from an unknown county bureaucrat unwise in the ways of the river to an international leader on water resources.

There’s still more to be written about the future of water in a region besieged by drought, but Mulroy’s days as a central character are numbered.

After 24 years at the helm of the Las Vegas Valley Water District and then SNWA, Mulroy, 60, announced last month her retirement.

Except for those four months in 2000, Mulroy said there’s never been an ideal time to retire, but with a team of trusted lieutenants in place and a recent round of rate increases, she finally feels comfortable stepping away from the job. She hasn’t set a date for her departure, wanting to ensure all the pieces are in place for an orderly transition, but by this time next year the SNWA will be under new leadership.

Her prowess helped Nevada earn respect among Colorado River states and transformed once-wasteful local water districts into a unified organization recognized nationally for its conservation efforts.

“We may only have only 2 or 3 million people in Nevada, but she has an equal voice on the Colorado River as the 37 million people in California,” said Sen. Harry Reid, a longtime Mulroy ally. “They have to respect us because of her.”

Mulroy's legacy will be tied to the success of the sprawling metropolis she helped water, the billions the authority spent doing it and the environmental costs of a controversial grab for groundwater in rural Nevada.

“Mulroy was not here when they first pumped water out of Lake Mead and into Las Vegas. It wasn’t supposed to be our main water supply, and now of course we are utterly dependent on it. That’s not her fault; her job is to make the water flow, and she’s done that,” said historian Michael Green, a professor at College of Southern Nevada. He places Mulroy in a category alongside Reid, casino magnate Steve Wynn and others for their impact on Southern Nevada. “You can argue about what she did, but you can’t argue that she did it.”

From novice to expert

Mulroy was an unlikely pick for the water district’s top job.

Born and raised in Germany as a U.S. citizen to an Air Force civilian father and German mother, she came to UNLV as part of a study-abroad program in 1974 to finish her senior year of college. She was studying German literature.

Mulroy had aspirations of continuing at Stanford University and eventually working for the State Department. Instead, she joined the staff of Clark County manager Richard Bunker as a $13,000-a-year analyst.

She quickly was promoted to lobbyist for the county and honed her political skills roaming the halls of the Legislative Building in Carson City.

After several short-lived administrative jobs, Mulroy was hired in 1985 as the Las Vegas Valley Water District's deputy general manager for administration, overseeing the agency’s finances and personnel.

She was relatively unschooled in the complex case law and political rivalries that ruled the river when she took over in 1989 as general manager of the water district, a situation that in many ways made her an ideal choice.

After years as an underrepresented afterthought on the river – a byproduct of little congressional clout, a small population and a fraction of the overall allocation, according to Mulroy – Southern Nevada stood on the precipice of unchecked growth. It would become Mulroy’s job to make sure a lack of water didn’t stand in the way.

Colorado River power brokers warned her Nevada would never see a drop over its original allotment – 300,000 acre-feet per year – set under a 1922 agreement. But Mulroy has never been accustomed to taking "no" for an answer.

Within two years of taking over the Las Vegas district, she managed to cajole the six other local water agencies to unite under the banner of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, with Mulroy taking the lead. And with that unified front behind her, Mulroy pitched the authority headlong into the Colorado River water fray, intending to make the best of Nevada’s situation.

“We knew we were playing on the fringe. We were rattling cages,” she said. “We said, ‘This little state down here can make the whole house of cards fall apart.”

The authority placed ads in Wyoming and Colorado offering to buy up ranchers’ allotments of Colorado River water rights, which led to allegations she was trying to steal other states' water.

All she wanted, Mulroy said, was a fair share of the Colorado for Nevada.

“There needed to be a dialogue among the seven states, California had to be weaned off of overusing the Colorado River and Nevada had to be given a pathway to access additional resources,” she said.

While she battled to raise Nevada’s position among the Colorado basin states, Mulroy also faced challenges locally.

Rapid growth was taxing the region’s water system. Sprawl was not slowing.

As the water district’s general manager, Mulroy served notice to developers in 1990 by issuing a moratorium on will-serve letters that guaranteed water for new projects.

“We had been giving out will-serve letters willy-nilly," she said. "The district attorney’s office said: 'You’ve got a liability you can’t honor. You don’t have the resources you’ve given out.' "

The new water authority began granting water to new projects again in 1991, but under terms that came with no guarantees and forced developers to bear the risk.

The rise of the megaresort proved another challenge to the waste-averse Mulroy, but like always, her unflinching position on the need for conservation won over the biggest powers on the Strip.

Like so many local public agencies, the water authority found itself caught in a growth surge accompanied by a huge spike in spending.

From its founding in 1991 until 1999, the authority's budget grew from $600,000 to roughly $150 million. Today, its operating budget is $454 million.

New pipelines, pumping stations and treatment facilities were needed to keep up with the constant influx of new residents.

Mulroy successfully persuaded voters in 1998 to approve a 0.25 percent increase in the county sales tax to pay for construction. With Reid’s help, Mulroy got a portion of the millions made each year from federal land sales around Las Vegas diverted to SNWA.

The funds helped fuel a $2.1 billion expansion of water treatment and delivery systems, a spending binge that 15 years later residents are just starting to feel through rate hikes.

Like many critical decisions throughout her career, Mulroy insists necessity forced the water system expansion.

“When you’re taking the population from 600,000 to 2 million, you’re going to need some facilities,” she said.

The question of finding enough water to put through those pipes remained, and Mulroy’s plan — force California to share some of the 800,000 acre-foot surplus it had been enjoying for years — was coming into place.

Her efforts put California on notice and positioned the Golden State as a water-hogging, water-wasting villain.

“The beginnings were pretty rocky. We were the ones with the most to lose,” said Jeff Kightlinger, general manager of Southern California’s Metropolitan Water District. “She was tough and she was calling us out, saying that we were not being responsible players on the river. I remember pushing back on her: ‘You’re a city in the desert; you don’t need to be telling Southern California what we should do.'”

Mulroy found an ally in Bruce Babbitt, interior secretary under President Bill Clinton and a former Arizona governor. Babbitt had once represented the rural Nevada counties opposing Mulroy’s groundwater grab, but the two found common ground in reining in California.

Negotiations on the river dragged in the late 1990s. Concerns were addressed, compromises were made.

“Pat is a very strong-willed person. She’s very upfront and very outspoken. Some people would say a little bit over the top at times,” said David Modeer, general manager of the Central Arizona Project, which provides water to large portions of Arizona, including Phoenix. “The bottom line with Pat is she is always willing to reach an equitable compromise.”

Deliberations resulted in a pair of landmark deals formalized in 2001 — one requiring California to share surpluses as long as the Colorado was flush and another allowing Nevada to bank part of its unused allocation in Arizona, building up a savings for a non-rainy day.

After 10 years with Mulroy on the job, it had become clear no one would stand in the way of her quest to keep Las Vegas in water.

Except, possibly, Mother Nature.

Dealing with drought

A staple of Mulroy’s tenure at the SNWA has been a weekly 9:30 a.m. Monday meeting with the senior staff “so we’re on all the same page,” she said.

Within SNWA's offices, Mulroy was known to shed her steely public persona.

"Inside the organization, the No. 1 thing people appreciate about Pat is the incredible loyalty to her employees. ... She treated people as the most important resource," said John Entsminger, SNWA deputy general manager and Mulroy's choice as her successor.

Of the roughly 1,000 Monday meetings over the years, one in March 2002 sticks with Mulroy.

“Kay Brothers (then the SNWA deputy general manager) walked in and said, 'Pat we have a serious problem,' ” Mulroy recalls.

A nascent drought throughout the western United States was worsening and showed no signs of slowing.

“That was the moment we started saying something is fundamentally different here.” Mulroy said.

After two years of drought, Lake Mead’s levels dropped below the point at which Nevada could overdraw the river, rendering moot Mulroy’s gains from the previous decade.

“We went from having a reliable 50-year water supply to nothing overnight. We couldn’t overuse (the river) any more,” Mulroy said.

Dire circumstances called for drastic, expensive measures that Mulroy again said were the only available choices.

Among the most visible was the authority’s “cash for grass” program, which provided $165 million worth of rebates to consumers who replaced their water-thirsty lawns with efficient xeriscaping. More than 130 million square feet of turf were ripped up, forever altering the suburban landscape but saving 7 billion gallons of water each year.

Consumption fell from an annual high of 330,000 acre-feet of water to 234,000 acre-feet — even while the valley’s population grew by 400,000 people.

With the Colorado's ability to meet Southern Nevada's water needs in question, the authority restarted its plans to build a pipeline to siphon groundwater from four rural counties, this time reducing its scope to target five valleys.

Ranchers, environmentalists and rural elected leaders objected.

“She’s really been hard to nail down on exactly what is she going to do up here. How much is the project going to cost? It’s been difficult to get into a real discussion with them,” said Gary Perea, a former White Pine County commissioner. “We are going to have all of the negative effects and none of the positives.”

Mulroy plowed ahead, driven again by what she saw as necessity.

“It’s not a matter of right or wrong, it’s the only solution. The one thing I’ve said over and over again is give me another solution that works,” Mulroy said.

She had her supporters, too.

“It wasn’t as if she has had a royal flush and she could pick whatever cards she wanted. She had very few hands,” Reid said. “She did the best she could. When it’s all over and done with, it will be good for the whole state.”

If the project clears legal battles, the debt-strapped agency still would need to find a way to pay for the pipeline, which is estimated to cost at least $3.2 billion.

The drought and the 2008 recession combined for a one-two punch that decimated the agency’s finances after a decade of runaway growth.

Rapidly dropping levels at Lake Mead forced construction of a third intake straw to ensure the authority can draw from its biggest water source.

The project has since gone $200 million over budget, to $800 million. Paying for it wouldn’t have been a problem had the recession not halted the valley's growth and, with it, the continuous stream of connection fees that had fueled the previous decade’s boom.

Over four years, the authority’s connection fee revenue, its main way of paying for new construction, dropped 98 percent from a high of $188 million to a recession low of just $3 million.

This pinch forced the authority to draw down reserves and delay projects. With the economy still sputtering and debt payments set to ratchet up, the authority turned to a rate hike in 2012. Mulroy describes the increase as the biggest, if not the only, regret of her career.

“We tried so hard to protect the community in 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011. We refinanced debt. We lived off our reserves. We probably pushed it too far.”

Included in the rate increase was a surcharge on rarely used fire lines — special dedicated water lines that provide more water pressure in case of a fire. Businesses previously hadn’t paid for those lines, and the surcharge led to the tripling of some customers’ water bills — several thousand dollars in some cases.

After community outcry, the authority cut the surcharge in half. A citizens committee’s subsequent review and endorsement of the reduced surcharge was proof, Mulroy said, it was the right and necessary course of action, even if it could have been handled better.

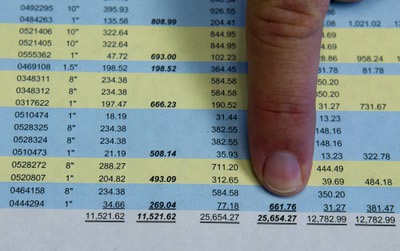

Jim Meservey, a principal of Storage One, points to the total of his current monthly water bills after surcharges Wednesday, May 30, 2012. The figure at left was the total bill for the prior month without the surcharge. Although the business is a low water consumer, the company has seen its water bills double or triple depending on the size of the water meters. In 2016, the surcharges are scheduled to double, he said.

“It all needed to happen,” she said. “I think the challenge was that no one had had an opportunity to talk about it for more time. We had to issue $300 million more in debt, we had to do something about our depleting reserves before we could sell that debt, and we had to sell the debt to build the third intake.”

Last month, the authority passed a second round of rate increases to cover escalating debt payments. The increase will cost residents about $5 more per month by 2017.

Water rates in Southern Nevada remain among the lowest in the western United States, but the measures Mulroy put in place to keep a growing Las Vegas awash in water came with a steep price tag that residents will be paying for long after she leaves office.

“If we hadn’t have had to go out and essentially spend almost another $1 billion on the third intake that has no growth component to it, we would have had a slight rate increase but never what we had in 2012,” she said. “We’re not the only water utility in the country that’s building facilities that we never thought we’d have to in order to adapt.”

The next chapter

As she introduced the keynote speaker at the recent SNWA’s annual WaterSmart Innovations conference, Mulroy showed no signs of battle weariness after 23 years leading the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

Launching into a variation of a speech she’s given countless times, Mulroy laid out a call to action for assembled water experts.

When she can’t bring the experts to her, Mulroy often travels to them, preaching her water gospel in places such as Israel, Singapore and Australia, among many others.

It’s in the international forum that Mulroy hopes to write her next chapter.

She said she’s developed a deep compassion for the social and humanitarian impacts of global water access.

“I took a job and found a passion,” she said. “I am convinced that one of society’s primary challenges over the course of the next 60 or 70 years is going to be water resources. The struggle is we have 19th-century infrastructure and 19th-century attitudes that aren’t equipped to deal with what’s ahead. I don’t intend to sit back and watch the daisies grow.”

She began contemplating retirement from her $310,134-per-year job in February, around her 60th birthday. She was starting to talk about transition planning after returning from a vacation in Italy in September when news of her departure leaked.

She hopes to spend at least the initial months of her retirement relaxing with her husband and two children, enjoying a personal life she admits has been “underdeveloped.”

Her time at the SNWA has lifted the authority’s profile and credibility along with the whole of Southern Nevada, turning the state into a force to be reckoned with on the Colorado River.

Many of the water officials Mulroy once did battle with now praise her and call her a friend.

Without the relationships born out of the conflict of the 1990s, officials said critical deals like the 2007 shortage guidelines, which spreads reductions in water supplies among the states as reservoir levels drop, would not have been possible.

Those relationships will likely be tested in coming years, as a depleted Colorado River forces a new round of negotiations and further cuts to allocations, although Mulroy won’t be around to see them.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy