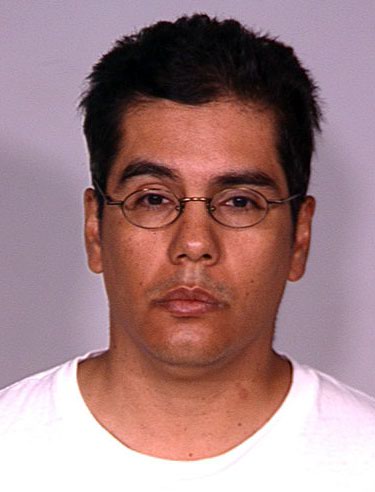

Melvyn Perry Sprowson Jr. listens to Chief Deputy District Attorney Jacqueline Bloth make arguments during his habeus corpus hearing Wednesday, April 30, 2014, in Clark County District Court. Sprowson, then 45, was arrested in 2013 after police found a runaway high school girl in his apartment. The pair met via Craigslist and started a relationship that turned sexual, authorities said. Sprowson is contesting charges filed against him.

Monday, Aug. 24, 2015 | 2 a.m.

The door of Room 803 was locked the morning police came to Rancho High School looking for Jason Lofthouse.

There had been reports the teacher was having sex with one of his students, but when a North Las Vegas police officer peeked through a window, the room looked empty. So he unlocked the door, walked in and in the corner found Lofthouse standing next to a girl. Lofthouse quickly backed away.

A few hours later, the girl told her mother everything.

How abuse cases are handled

The Clark County School District has a process for handling allegations of educator abuse.

1. Allegations are brought to school staff or school district police.

2. School district police investigate and conduct interviews.

2a. If victim is under 14, local law enforcement takes over the investigation.

If there is evidence of illegal behavior ...

1. Police arrest and detain the suspect.

2. The justice system takes over and the case proceeds through court.

If there is evidence of inappropriate behavior that’s not illegal ...

1. The case is forwarded to the Clark County School District Employee Management Relations board made up of district administrators.

2. District officials review the case and decide if it requires disciplinary action.

3. Depending on the severity of the offense, the employee is either given a warning or dismissed.

3a. An employee can choose to resign rather than go through the firing process.

If an employee challenges a dismissal ...

1. The case goes to arbitration.

2. The district must prove guilt; the employee must prove innocence.

3. An independent arbitrator decides whether to uphold the disciplinary action or absolve the employee of wrongdoing.

What about Title IX

Most people think of Title IX only as applying to gender discrimination in athletics, but the federal law also bans sexual harassment and abuse in schools and requires every school to have a person on staff to make sure the law is being enforced.

That doesn’t always happen.

In an informational guide the Clark County School District sent to parents, the only mention of Title IX is an assurance that the district doesn’t discriminate. The district’s web page on Title IX doesn’t mention anything about sexual harassment or abuse, and district officials don’t maintain a list of compliance officers at schools.

When reached by phone, staff at the district’s three largest high schools, Rancho, Coronado and Green Valley, couldn’t name their school’s Title IX coordinator.

“What’s Title IX?” a receptionist at Green Valley asked. “Why would we need that? We don’t discriminate.”

After five minutes on hold, she returned with the name of the assistant principal.

Green Valley was one of seven schools that employed 48-year-old Kelly Hoffman as a substitute teacher. Hoffman admitted to luring a 15-year-old girl to his house for sex. He is awaiting sentencing.

Her account: Lofthouse, 32, and she had started as friends, but then she began skipping seventh period to hang out with him alone in his classroom. That led to making out, which led to touching and her performing oral sex on him.

On May 20, after Lofthouse suggested they get a hotel room, the pair skipped class to drive to the Aliante. There, they had sex several times before Lofthouse drove the girl home. Eight days later, they checked into a hotel room at the Cannery and did it again. Surveillance footage from the Cannery showed the two kissing in an elevator. Work logs and attendance sheets at the school showed them absent both days.

In June, on the last day of school, officers entered Room 803 and arrested Lofthouse on suspicion of sexual misconduct with a student. He now faces multiple felony charges of kidnapping and sexual misconduct with a minor. He has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial.

While shocking, there’s nothing unordinary about the allegations. Advocates say there is a hidden epidemic of school employees sexually abusing students they are entrusted to protect.

A HIDDEN EPIDEMIC

Over the past 10 years, more than 30 Clark County School District employees have been arrested for alleged sexual misconduct. Six served jail time, and six had charges dismissed. The rest were given probation or have charges pending.

From 1994 to 2005, more than 50 school district workers were arrested. In just three months this year, from April to June, five Clark County School District workers were charged with sexual abuse.

That’s just here in Clark County. The best available study on the subject suggests about 10 percent of students nationally suffer sexual abuse in school, be it lewd comments, exposure to pornography, sexual touching or assault. In two-thirds of the cases, the abuse was physical.

If those numbers hold true, that’s millions of students victimized.

Terry Abbott, a former chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Education, believes the problem is becoming even more common. According to data collected by his public relations firm, Drive West, an average of 15 teachers nationally are arrested every week on suspicion of sexual abuse.

Still, it’s hard to know just how deep the problem goes. Much of the abuse goes unreported.

Why?

“People don’t listen to kids,” said Charol Shakeshaft, one of the nation’s leading researchers on the subject.

FIGHTING BACK

From her home near the hills of the southern valley, Terri Miller wages a quiet war.

Every morning, she sits in front of her laptop with a spread of worksheets and folders. It’s where she conducts business as president of Sesame, the group she founded to pressure lawmakers to strengthen regulations and punishments for teachers caught sexually abusing students.

“This is my folder on Peterson,” she says, pulling out a workbook of newspaper clippings.

In 1982, Miller, then 24, moved to Pahrump with her husband and children. They saw the community as the perfect place to raise a family.

One day after aerobics class, Miller said, her instructor announced she was getting a divorce. Miller said the instructor had caught her husband, Joseph Peterson, a respected teacher and coach at Pahrump Valley High School, in bed with a female student.

With a little digging, Miller discovered Peterson was infamous among students for his sexual advances. He walked in on girls in the locker room, found ways to look up their skirts in class and gave them preferential treatment in return for sexual favors, she said.

“Everybody knew what he was doing,” Miller said. “It was common knowledge and talked about openly at bridal showers, at the pool, at our aerobics classes.”

When Miller went to the principal, she was told the stories were just rumors, she said. School board members, many of whom were friends with Peterson, refused to get involved. When she brought her concerns to the PTA, other parents told her to leave it alone.

With her daughters about to enter high school, Miller took action. She started keeping a list of potential victims and calling local law enforcement and attorneys. That led to many nights alone at her computer, sifting through notes.

“All of a sudden, dinner wasn’t on the table at 5 p.m. anymore,” Miller said. “I became obsessed.”

Miller’s efforts led to one of the most high-profile cases of teacher sex abuse in the country and put her on a lifelong path of fighting to protect children.

FAILING TO ACT

During the course of her investigation, Miller was bothered most by how little school employees and district officials seemed to care about Peterson’s history of abuse.

A bus driver filed three complaints after Peterson acted inappropriately with students on the bus, but the complaints were ignored and the driver later was fired, Miller said. She said female students even had a term for girls who got preferential treatment in return for sexual favors: “Pete’s Pets.”

While the Peterson case is extreme, the Clark County School District has faced multiple lawsuits from families who say school officials failed to act on tips about sexual abuse.

In 2002, the parents of a 14-year-old Mojave High School student sued the district, alleging that administrators knew about a 27-year-old soccer coach’s flirtatious behavior but failed to act. Case records show neither the principal nor the assistant principal referred the matter to officials, child and family services, or any police or sheriff’s department. Months later, the same officials were notified that the coach and the girl had been having sex, and the man was arrested.

“Schools do very little about it,” Shakeshaft said. “They don’t listen to kids when they give them red flags. They don’t follow up, they don’t suspect teachers, and they won’t even believe it when they’re told.”

In 2009, a lawsuit was filed against the Clark County School District by the family of a Durango High School student who had sex with her driver education teacher, Angel Menes. Family members said a relative and another student warned the district about Menes’ behavior more than a year before he was arrested. District officials said they could find no such letter, according to court documents. Menes was sentenced to up to four years in prison; he served time and was released.

Even when there aren’t people to come forward, red flag behavior typically abounds in cases of educator abuse, experts say. Most common is “grooming,” when a teacher shows special interest in a student, giving preferential treatment, confiding secrets, sharing gifts and making the child feel special.

An analysis by The Sunday showed nearly every case of educator abuse in the Clark County School District over the past 10 years involved grooming.

When police interviewed the Rancho student involved in the Lofthouse case, for example, she told them Lofthouse was friends with a lot of his students. Though not always, that kind of personal attention often is a warning sign of sexual abuse.

In another case, Michael Barclay, a Lied Middle School history teacher and basketball coach, offered to drive a student to practice while his mother worked. Instead, Barclay often drove the boy to his house, where he tried to get him to perform oral sex, according to police reports. The boy’s mother realized something was wrong when the boy refused to go to practice. Barclay was sentenced to up to 10 years in prison but was granted three years probation instead.

A Cashman Middle School student described her teacher, Mikhial Lerma, as her “best friend.” She regularly hung out in his portable classroom after school, discussing topics that got more inappropriate as time went on, from talk about smoking weed to him daring her to kiss him — which she did, according to police reports.

“Children grow up very confused,” Miller said. “They know teachers have the ability to pass them or fail them. Think about how much responsibility and authority a teacher has.”

THE WORST OFFENSE

Whenever Mitch Maciszak hears a rumor about a teacher abusing a student, the Clark County School District police detective swings into action.

“It’s all hands on deck,” he said. “This is our homicide.”

A team of five detectives works each case, while patrol officers go from school to school gathering evidence and interviewing witnesses. The job isn’t easy.

“Most law enforcement agencies like to have a victim,” Maciszak said. “But because we are school police, we take it on pure rumor.”

Often, the only witnesses are students — children who don’t want to get the teacher in trouble.

“How hard is it for a student to speak up against a teacher, especially a revered one? These students suffer so much backlash when they do the brave thing and tell,” Miller said.

There’s another obstacle that makes it harder for school police to catch bad teachers: cellphones and social media, which allow teachers and students to communicate out of view.

When the mother of the Rancho student found texts on the girl’s phone to someone named Jason, the girl covered her tracks by changing his name to a smiley face emoji. In Mikhial Lerma’s case, the girl saved his number under “Person.”

An examination of teacher sex abuse cases in the Clark County School District from 2005 to 2015 showed that half included some kind of electronic communication between the teacher and the victim, including all but three of the 15 cases from the past five years. Of those three, two involved elementary school-age students.

“Most cases that we work have a tie to social media,” Maciszak said. “The technology we battle on a daily basis is ever changing.”

In a 2014 case, police reported that Tanikka Queen, a 23-year-old substitute geography teacher at Hyde Park Middle School, exchanged more than 2,400 text messages, 108 phone calls and 38 photos with a 15-year-old boy. She also had sex with him, according to police reports.

“Don’t save my number as anything obvious,” she instructed the boy in a text. “Make it a code name.”

He saved it as “cachetona,” Spanish for “chubby cheeks.”

Queen was charged with sexual conduct between an employee and a pupil and luring with the intent to engage in sexual conduct. She pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 10 years in prison but was granted five years probation.

In an almost identical case in 2013, authorities reported that Foothill High School teacher Amanda Brennan exchanged 1,000 text messages with a 15-year-old boy over nine days. The boy, a special education student, later attempted suicide after being humiliated and bullied by other teachers, according to a lawsuit filed by the family. Brennan was charged with luring children or mentally ill persons with the intent to engage in sexual conduct and was sentenced to four years in prison but was granted five years probation.

Technology “is not only part of the epidemic, it’s driving the epidemic,” said Abbott, of the Department of Education.

The Clark County School District has no policy forbidding teachers from communicating privately with students. Teachers are free to friend students on Facebook, chat with them online and exchange text messages, in large part because the teachers’ union negotiated disciplinary procedures that say “the personal life of a teacher is not an appropriate concern of the district.” That same rule means the district can’t do anything about a teacher who posts nude photos online, a district spokesperson said.

John Vellardita, executive director of the Clark County Educator’s Association, said the union would honor any new social media policy enacted by the district.

“There’s no reason that a school employee should have secret communication with a student in the middle of the night,” Abbott said. “None.”

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

In many cases, perpetrators are caught. But what about teachers who aren’t convicted?

What would have happened if, for example, a school district officer hadn’t been sitting in his patrol car at Cashman Middle School when Lerma and his student left a portable classroom around midnight? Believed to have been found out, Lerma turned himself in the next day.

When the justice system’s hands are tied, when there’s no evidence or a teacher’s behavior is inappropriate but not illegal, school districts must police themselves.

The Clark County School District has some written rules for employee conduct but mostly defers to Nevada law.

The problem is, many grooming behaviors are not illegal, and the only offenses for which school employees can be fired without warning are being convicted of a crime or the vague offenses of “immorality” or “dishonesty,” which are determined by school district employees. A coach who gives a student a back rub or a teacher who presents special gifts to students can argue they are innocent gestures and escape with a warning. If a teacher crosses the line again, the district can fire him or her after one warning.

But in most cases, teachers suspected of abuse simply resign, Clark County School District disciplinary officials said. Quitting, either of their own volition or with encouragement from the district, allows bad teachers to quash accusations and seek work elsewhere. For school districts, a voluntary exit is a much cleaner and easier process than a dismissal.

The problem arises when that teacher arrives at the next district. Terri Miller calls it “passing the trash” — when a disgraced teacher is forced out of one district only to get a job in another.

That’s what happened with Melvyn Sprowson, who left the Los Angeles Unified School District after being accused of touching young girls. The charges were dropped, so nothing came up when Clark County officials ran a criminal background check on him.

Sprowson, then 45, was arrested in Las Vegas in 2013 after police found a runaway high school girl in his apartment. The pair met via Craigslist and kindled a relationship that turned sexual, authorities said. Sprowson is contesting charges filed against him.

“We now take extra steps to verify,” Clark County School District Human Resources Chief Staci Vesneske said. “We’re digging deeper.”

The Clark County School District now requires every job candidate to sign a release allowing the district to pull past personnel files. But not every school district does the same. If an employee resigns from the Clark County School District amid allegations of inappropriate behavior, the district keeps those records in the person’s personnel file and will share them with another district if asked. But few school districts request the records.

Teachers who are fired can choose arbitration to have allegations thrown out. In those cases, an independent arbitrator acts as a judge and jury, with the power to overturn firings. The accused receives a union negotiator at every step, whose job it is to do anything possible to put the teacher back into the classroom.

While the process is meant to give employees due process if they feel unfairly targeted by administrators, it is not designed to be child-friendly. If a student doesn’t want to testify in arbitration proceedings, it’s virtually impossible for the district to win. As one school district lawyer put it: “If I can’t get Johnny in there to say it happened, I’m dead in the water.”

Deputy District Attorney Jim Sweetin has worked in the special victims unit for 11 years and has seen a rise in abuse cases in schools. He said district disciplinary proceedings makes it hard to go after teachers suspected of crimes.

“I’ve seen (cases) where there’s definitely a lot of smoke but the teacher just keeps teaching,” Sweetin said.

Vellardita said the problem isn’t the arbitration process, it’s the district failing to properly vet candidates.

“We’re not the employer,” Vellardita said. “This is a classic case where the school district avoids its responsibility.”

There’s no way for parents or the public to find out which, or even how many, employees the district has investigated for sexual harassment or abuse, nor how many sexual abuse cases have gone through arbitration. That information is considered confidential because it could hurt someone’s reputation.

It’s the same reason school district police lump rumors of sexual abuse in with a daily list of “suspicious circumstances” at schools.

“Let’s not cause grief for someone who may have done absolutely nothing wrong,” Maciszak said.

PUSHING BACK

After years of getting nowhere, Miller made a breakthrough. She found a former student who had worked on the school yearbook with Peterson as an adviser. The girl told Miller she had been working alone one night when Peterson cornered her and raped her. Unlike Peterson’s other victims, she was willing to go public.

Peterson was arrested just before Thanksgiving 1994. Two years later, he was sentenced to five years to life in prison and served 16 years before being released on parole in 2012. He has since moved to Wyoming, where he’s listed as a registered sex offender.

At the time, Miller felt vindicated. But now, as she scrolls through stories of teachers abusing students, she is conflicted.

“It just should not have been that hard,” Miller said.

While advocates have succeeded in getting stricter laws on the books, they say school districts also must confront the problem.

“Districts need to be much more aggressive about training teachers,” Abbott said.

Incoming Clark County teachers sit through an hourlong presentation by a district lawyer, who warns them about crossing the line with students. Teachers already in classrooms have to take an online class annually. That’s the extent of the district’s training, which experts say should be much more thorough.

“An hour is not enough,” Miller said. “They need to hear from victims. It needs to be put right in their face so they get it.”

Since the 1980s, lawmakers have banned sexual relationships between school employees and students regardless of the age of consent, tightened the language in sexual abuse laws, and as of this year, banned sealing court case records involving the sexual abuse of students. In July, Sen. Dean Heller and Rep. Joe Heck sponsored a bill that would expand federal grants for sex abuse training in schools.

With lawmakers every step of the way, making calls from her dining room table, is Terri Miller.

“This is the ultimate goal: to prevent children from being harmed and to make sure schools are the safest place for our children,” Miller said. “Because they should be.”

•••

TIPS FOR PREVENTING ABUSE

Experts say vigilant parenting is the first line of defense in preventing sexual abuse. Most children are abused by someone they know and trust.

Here’s what you can do to try to keep your children safe:

1. Learn to recognize the signs of grooming behavior, which include an adult paying special attention to a child and/or communicating with him or her via social media.

2. Pay attention to changes in your child’s behavior. Does he become irritable when a certain school employee is mentioned? Is she withdrawing from school activities? Or is he or she spending a lot of time with a certain teacher?

3. Find out who is your child’s school’s Title IX coordinator. If the school doesn’t have one, demand one.

IF YOU SUSPECT ABUSE

Report suspected abuse directly to a local law enforcement agency, such as Metro Police or Henderson Police, as well as school district police. You can reach the Clark County School District Police Department at 702-799-5411.

SIGNS OF SEXUAL ABUSE

No one sign means a child was sexually abused, but the presence of several suggests parents should begin asking questions and consider seeking help.

Has nightmares or other sleep problems without explanation

Seems distracted or distant at odd times

Has a sudden change in eating habits

Experiences sudden mood swings: rage, fear, insecurity or withdrawal

Seems eager to discuss sexual issues

Develops a new or unusual fear of certain people or places

Refuses to talk about a secret shared with an adult

Talks about a new older friend

Suddenly has money, toys or other gifts without reason

Begins to think of self or body as repulsive, dirty or bad

Exhibits adult-like sexual behaviors, language or knowledge

In younger children

Begins behaving like a younger child (bed-wetting, thumb sucking)

Has new words for private body parts

Resists removing clothes at appropriate times (bath, bed, toileting, diapering)

Asks other children to behave sexually or play sexual games

Mimics adult-like sexual behaviors with toys or stuffed animals

In adolescents

Self-injury (cutting, burning)

Inadequate personal hygiene

Drug and alcohol abuse

Sexual promiscuity

Running away from home

Depression, anxiety

Suicide attempts

Fear of intimacy or closeness

Source: Stop It Now

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy