Monday, Sept. 7, 2015 | 2 a.m.

What is a rape kit?

Rape kits, also known as sexual assault forensic evidence kits, typically are collected by a nurse who has undergone special training to perform the examination. Doctors and nurses without special training also can perform the exam by following instructions provided in the kit, but the Department of Justice recommends special education for examiners.

Victims are advised not to bathe, shower, use the restroom, change clothes or comb their hair before going to the hospital, to preserve as much evidence as possible, although an exam can be performed regardless.

Where do I go to get examined?

• 16 years or older University Medical Center

• 16 and younger (if the assault was recent) Sunrise Children’s Hospital

• 16 and younger (if the assault happened some time ago) Children’s Advocacy Center

Do I have to share my name?

Victims can have evidence collected anonymously as a “Jane Doe/John Doe” rape kit and choose later whether to associate their name with the evidence and/or report the case to law enforcement.

How much will it cost?

Under the Violence Against Women Act, states or other government entities must pay all out-of-pocket costs of forensic medical exams for victims of sexual assault. However, victims may have to pay for associated medical care.

When should I do it?

Exams should be done within 72 hours of an assault, Metro Police recommend.

How long will it take?

4-6 hours. It can feel intrusive. However, nurses try to do as much as they can to make the victim as comfortable as possible.

What's in a rape kit?

• Instructions for the examiner

• Forms to document the procedure and evidence gathered

• Tubes and containers for blood and urine samples

• Paper bags for collecting clothing or other physical evidence

• Swabs for biological evidence collection

• A large sheet of paper on which the victim undresses to collect hairs and fibers

• Envelopes, boxes and labels for each stage of the exam

• Dental floss and wooden sticks for fingernail scrapings

• Glass slides

• Sterile water and saline

What to expect during an exam

1. The examiner obtains a complete medical history from the victim.

2. The victim stands on a large sheet of paper and undresses, to catch any hairs or fibers that might fall from her body.

3. The victim’s clothing and the sheet are collected to be tested for evidence.

4. The examiner notes any injuries observed and treats them as needed.

5. The examiner swabs the victim’s body, including the skin, genitalia, anus and mouth; scrapes under the victim’s fingernails; and combs through the victim’s hair to collect biological samples such as saliva, blood, semen, urine, skin cells and hair.

6. If the victim consents, the examiner photographs the victim’s body from head to toe to ensure evidence of bruising or other injuries is preserved.

7. The examiner labels and seals the evidence to prevent contamination.

What should survivors do if they had a rape kit collected but don’t know if it was tested?

Survivors should contact the law enforcement agency that handled their case to check on the status of their rape kit. Having the name of the police detective or prosecutor assigned to the case or any tracking numbers associated with it, like the police report number or the criminal court case number, can be helpful. The Joyful Heart Foundation recommends survivors work with a local victim advocate to facilitate this process, since advocates often have existing relationships with local law enforcement and knowledge of the procedures. Advocates can assist victims who want to have their kits tested, even if the victims did not want them tested previously. Law enforcement may not always be able to answer all of a survivor’s questions immediately, particularly if the case is moving forward to trial, to ensure that no evidence or witnesses are tainted.

How do victims hears about the results?

Testing rape kits is only one piece of the puzzle.

Once evidence is successfully collected from a kit, the DNA is entered into the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, a criminal justice database. If there’s a hit, detectives and victim advocates have to decide how to inform the victim — if they even want to be informed.

Notifying victims is a process easier said than done, particularly when some cases are 30 years old. Some victims may have changed their addresses and phone numbers; others may not want to be reminded of the trauma after so many years, said Daniele Dreitzer, executive director of the Rape Crisis Center Las Vegas.

“It becomes an issue of how do we offer victims the most options for what would make them comfortable moving forward,” Dreitzer said. “Do they even want to know if there’s a positive hit at this point? Or have they moved on in their lives to the point where they’ve tried to put it past them?”

A statewide sex assault kit working group — made up of representatives from the Attorney General’s Office, the state’s two crime labs and the Rape Crisis Center, among others — is working to address the issue by creating a statewide victim notification policy. The committee meets every other month.

The goal, Dreitzer said, is to offer victims the most options for how they want to be notified of a database hit, if at all. While one person might prefer the information delivered in person, others would rather an email or a letter.

Additionally, because Las Vegas sees so many tourists pass through each year as well as a high turnover of residents, locating victims can be difficult, Dreitzer said.

“When we think about having to notify people from a backlog that goes back so far, how do you notify people who are from other states” Dreitzer said. “We are a very transient place, which is an issue unique to Las Vegas.”

One solution, Dreitzer said, is putting up airport advertisements to let out-of-towners know Las Vegas police are testing rape kits collected during a specific time period. It would ask victims to reach out and opt into being notified of a database hit and enable them to choose how they’d like to be contacted.

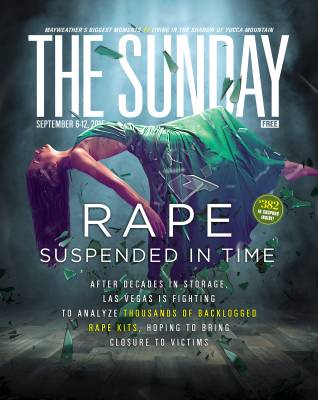

It’s 1985 or 2015; morning or night; summer or winter. She could be your sister, your mother, your daughter, your friend.

An assault happens.

Friends urge her to go to the hospital to be examined. She does.

She undresses on a sheet of paper and turns her clothes in to be tested and used as evidence. Her body is examined, scrutinized; every bruise, every mark noted. She is swabbed for vital pieces of evidence. Pictures are taken.

The nurse and victim advocate speak gently to her, but all she can think about is showering and putting on new clothes. The exam takes four hours.

The kit is sealed, turned over to police and stored as evidence. But it never gets tested.

This is the story of tens of thousands of survivors of sexual assault whose rape kits sit untested in evidence lockers across the country as the assailants go free.

The backlog

Metro Police alone had 5,643 rape kits — including a handful that date to 1985 — in their backlog as of late July. Eight other local agencies count 739 more. That means Metro’s forensic lab — one of only two labs in the state that test rape kits — has 6,382 backlogged exams to process.

The lab has been testing about 100 rape kits in-house per year, Director Kimberly Murga said. Cities and states across the nation have started testing rape kit backlogs, spurred by the success of other communities in identifying serial offenders.

But “when we’re looking at 6,300 kits lined up at our door, the only way we can process all of them is to reach out and acquire some additional resources,” Murga said.

The lab is working with agencies across the nation to secure funding to test the backlog and to negotiate lower rates to test each kit. Exams typically cost about $1,500 each to test, Murga said. The lab has worked with two private DNA testing companies to secure a discounted rate of $625 per kit if the lab tests in bulk, but even so, the lab is staring down an almost $4 million bill.

To help ease the burden, Murga and her staff applied for two grants: one through the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office that would provide $2 million to test rape kits, enabling the lab to process about 2,970 exams, and one through the U.S. Justice Department to test about 1,300 rape kits, hire victim advocates and pay overtime for investigators.

Between the two grants, the lab would be able to test about 4,270 kits from Southern Nevada’s backlog — about two-thirds of the total. The Nevada Attorney General’s Office is evaluating whether there is state money available to address the rest, Murga said.

Meantime, the lab is looking to test its kits however it can. Officials sent about 120 rape kits to a National Institute of Justice-FBI research project to have them tested.

“I have to be honest: It’s going to take several years to move through this backlog as it stands now,” Murga said. “But we’re in a good position, as many other states have been successful in this endeavor.”

From cold case to trial

Valley police and prosecutors are preparing for new leads on cold cases, as rape kits often provide crucial evidence needed to investigate cases and move them through trial.

Using older rape kits that already have been tested, detectives found information that has provided essential leads. The kits not only have identified suspects but also have tied cases together, helping police locate serial offenders, Metro Sgt. Raymond Spencer said.

That’s why, moving forward, Metro’s forensic lab intends to test every rape kit it encounters. The hope is police will be able to figure out whether a sexual assault involving acquaintances actually is part of a pattern of serial offending and allow police to make more informed decisions when investigating, Spencer said.

DNA evidence also plays a crucial role at trial, partially because juries expect to see forensic evidence in cases of sexual assault, said James Sweetin, chief deputy district attorney in the special victims unit. Because many TV shows depict DNA evidence as integral to sexual assault investigations, attorneys have to explain to juries why in some cases it doesn’t exist.

If evidence can be analyzed and suspects named, the District Attorney’s Office should be able to prosecute all of Southern Nevada’s cold cases involving rape kits — even the oldest dating to 1985 — as long as a report was made to police, Sweetin said. In Nevada, filing a written police report of sexual assault stays the statute of limitations. This session, the state Legislature changed the statute of limitations on rape charges from four years to 20 years.

“Normally, sexual assaults aren’t committed as an isolated incident,” Sweetin said. “It’s normally something a perpetrator of sexual assault isn’t only going to do once. They’re going to do it on multiple occasions, and taking someone like that off the street is positive for our community.”

On a broader scale

The issue extends beyond the valley. During his election campaign last fall, Attorney General Adam Laxalt pledged to dedicate a team of investigators and lawyers to significantly reduce or eliminate the backlog of rape kits statewide before the end of his first term.

The first task: determine how many rape kits are backlogged in Nevada. A spokeswoman from Laxalt’s office confirmed there is no complete count of all the untested rape kits in the state, though she said officials are working to collect that information.

The Washoe County Sheriff’s Office, whose forensic lab tests rape kits from Washoe County and 13 rural northern counties, counts 62 untested kits, but it has no record of how many untested kits are in the Reno or Sparks police departments or any other agency in the north, said Renee Ismari, director of the office’s forensic science division.

In fact, Reno police don’t even know how many kits are in their backlog, Detective Sgt. Marcia Lopez said. All of the department’s rape kits — both tested and untested — are stored together in an evidence room. So not only would police have to perform a count by hand, they also would have to individually cross-reference each case number with a database to determine which ones haven’t been tested.

“There’s no way to track them outside of sending somebody into the freezer with a freezer suit and hand mucking them,” Lopez said.

All rape kits from cases with an unknown offender — about 15 percent — are sent immediately to the lab for testing, Lopez said. The rest become part of the unknown backlog. Of the 85 or so rape kits the lab receives each year, about 72 won’t be tested. And the department’s backlog dates back at least 19 years to 1996.

“In a perfect world, we’d send them up every single time for testing and track them a lot better,” Lopez said. “But we’re so far behind that now we have to figure out what the best course of action is so we don’t fall further backward.”

The first step is determining the scope of the problem, said Ilse Knecht, senior policy and advocacy organizer at the Joyful Heart Foundation, which advocates for ending rape kit backlogs.

“Once a community knows their numbers and they go in and make a full accounting of how many they have, the very obvious next step is to deal with it,” Knecht said. “We’re pushing them to get in there, find out what you have, and that’s a jumping-off point for reform.”

For now, the Attorney General’s Office continues to work on a plan to process the backlog, and a spokeswoman from the office said she had “nothing new to report.”

How did the backlog begin?

1) Old testing techniques were complicated, slow and sometimes inaccurate

DNA really wasn’t used in the forensic arena until the late 1990s or early 2000s, said Kimberly Murga, director of the Metro Police forensic lab. Metro’s lab brought DNA testing online in 1999. That means the kind of DNA testing that happens nowadays wasn’t common practice when the oldest kits in the backlog were collected.

When DNA finally rolled out, there was a disconnect in understanding its value and how it could solve cases, Murga said. Previous to that, labs could run a serology test, a precursor to DNA testing, on samples, but the accuracy was so low, convictions were as low as 1 in 33 people, Murga said.

DNA testing technology has progressed by leaps and bounds since then. In the early days, a test might need eight weeks and a stain the size of a quarter, Murga said. Now, technicians can retrieve DNA from the size of a pinhead and much faster.

2) Detectives did not always order analysis of rape kits received

Another reason for the backlog is detectives have discretion about whether to request a rape kit be tested, Murga said. If detectives thought other evidence was more valuable in a case or if victims decided they didn’t want to prosecute, detectives wouldn’t request the kit be tested.

That is changing as cities test backlogs and kits come back tying cases together.

“They’ve discovered that these untested kits are a treasure trove of information,” Murga said. “They’re obtaining links to serial offenders. We anticipate that with our backlog, we’ll encounter a lot of serial rapists.”

Why is Las Vegas’ backlog so large?

Las Vegas ranks third — trailing only Memphis and Detroit — among 22 cities with reported but uncleared rape kit backlogs, the Joyful Heart Foundation found. That said, 18 cities failed to responded to the organization’s request for a count.

“We do have a large backlog,” Murga said. “But what you’ll notice is that there are many, many agencies that have not reported what they have.”

Detroit has been working slowly through its 11,341 kits since 2010. Officials had tested about 10,000 kits — which led to the identification of 456 suspected serial offenders with crimes in 32 states, including Nevada — as of late June.

“There’s kind of an inspirational quality that comes out of looking at cities that have seen successes” said Ilse Knecht, the foundation’s senior policy and advocacy organizer. “These communities are really setting the bar for other communities and showing you can bring justice and healing to survivors.”

Why are officials testing the backlog now?

Metro Police have been concerned about the backlog since about 2008, Murga said. But testing is taking off now because of more awareness on both a local and a federal level about the impact these kits can have.

For instance, Congress recently approved a spending bill that allocated $41 million in grant money that local agencies can apply for to test rape kit backlogs.