The interior of a vacant home near Viking Road and Eastern Avenue Sunday, Feb. 28, 2016. The home has been damaged by squatters and teens who break in to have parties.

Monday, April 4, 2016 | 2 a.m.

Related Story

Bill Moore woke up at 5 a.m., as he always did, and gave his companion, Jean Main, a kiss goodbye when he left for work a few hours later.

He would later testify in court that the next time he saw her, she was lying on the bathroom floor, shot in the head. Main, a great-grandmother who took pride in tidying up the suburban Las Vegas house she shared with Moore, was home alone that spring morning when, police say, an ex-con with tattoos on his face and neck drove up, looking to rob the place.

How did Las Vegas become a squatter magnet?

• Housing market collapse: The recession obliterates the once-roaring Southern Nevada housing market and takes the city’s economy down with it. Tens of thousands of people are laid off and lose their homes to foreclosure, leaving the valley glutted with vacant houses.

• High unemployment rate: The economy improves, but effects of the recession stubbornly linger. Las Vegas’ unemployment rate falls to 6.5 percent in January from 14 percent in 2010, but it’s still second-highest among large metros, says the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

• Foreclosures: In 2015, the valley posts the 17th-highest foreclosure rate among large metro areas. Nearly 12,500 properties — or about 1.5 percent of local homes — are hit with a foreclosure filing, up 3.4 percent from 2014, says RealtyTrac. In the fourth quarter of 2015, 21 percent of mortgage borrowers in the Las Vegas area are underwater — meaning their debt outweighed their home’s value. That’s down from 71 percent in early 2012 but still highest among large metro areas, according to Zillow.

• Mortgage payment problems: Although the foreclosure rate falls, plenty of people remain behind on their mortgage, and those borrowers pack their bags and bolt more often here than in other cities, adding to the overstock of abandoned houses. By mid-2015, 34 percent of valley homes in the foreclosure process but not yet bank-owned had been vacated by the owners. That amounts to some 1,940 homes, up 16 percent from a year earlier, according to RealtyTrac.

Bayzle Morgan allegedly went in, took Main into a bathroom, pistol-whipped her in the head repeatedly and shot her once in the back of the head. He then ransacked the house, stealing costume jewelry, cash and electronics.

Morgan also was staying in the suburbs, a few miles away in a one-story house on Wedlock Lane. But that residence, located near parks and schools, wasn’t really his, police say.

According to them, he was squatting.

Las Vegas’ once-devastated housing market has turned the valley into a squatter’s paradise. The real estate industry has improved the past few years, but with thousands of empty houses still out there — after foreclosures, layoffs and other financial woes pummeled the region — police are getting a rising volume of calls about suspected squatters valleywide.

Squatters break into vacant homes or even “rent” from people who climbed in, changed the locks and drew up a bogus lease. Some keep the properties in nice shape, but plenty of them trash the house, use drugs or have weapons, creating pockets of poison in local neighborhoods.

In Morgan’s case, the house had been abandoned after the owner died. But many homes occupied by squatters are vacated by people with financial problems.

“If you’re willing to break into a home and move in, what else are you capable of?” said Assemblywoman Victoria Seaman of Las Vegas, a real estate agent and a sponsor of a new anti-squatter law.

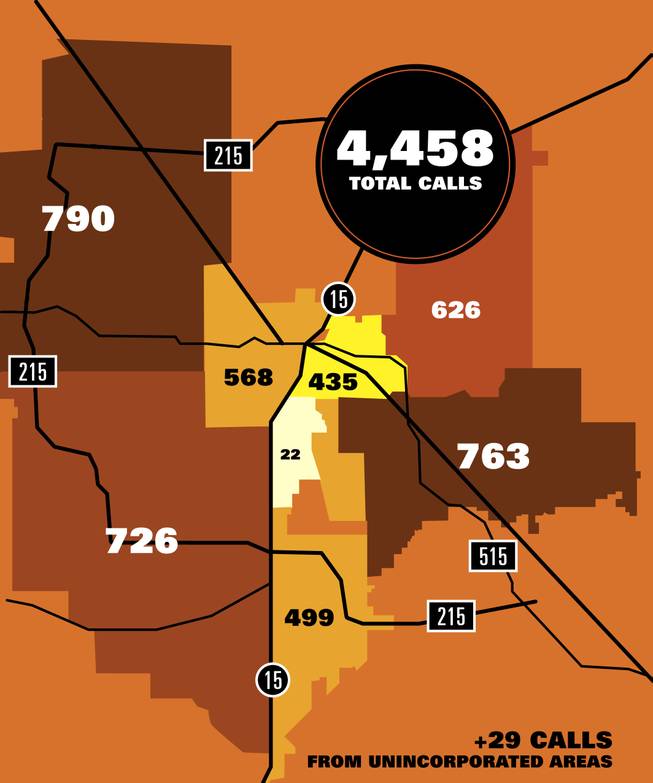

Metro Police said they received at least 4,458 squatter-related service calls last year, up 24 percent from 2014, 69 percent from 2013 and 169 percent from 2012.

Squatters are in older, lower-income neighborhoods; more-affluent communities; and middle-class areas that grew rapidly during the bubble last decade and got slammed by foreclosures during the bust. Metro’s suburban Northwest Area Command gets the most calls — 790 last year, up from 285 in 2012.

“They are everywhere,” said Officer Jose Martinez, who targets squatter homes in the northwest valley. “There’s a very good chance that you have a squatter within a half-mile of your own house right now.”

They have plenty of options. Some 2.1 percent of Las Vegas-area homes, or about 13,360 properties, are vacant. Nationally, 1.6 percent of homes are empty, according to RealtyTrac.

Las Vegas’ share is tied for 11th among the 50 largest metro areas.

Police officials and housing pros have said the new law, Assembly Bill 386, would let authorities more easily crack down on squatters. It established such criminal offenses as housebreaking, or forcibly entering a vacant home to live there or let someone else move in without the owner’s consent; unlawful occupancy, or moving to an empty home knowing you don’t have permission to be there; and unlawful re-entry, or going back into a house without permission after the owner reclaimed the property. Violators can face gross misdemeanor or felony charges.

Since the law took effect Oct. 1, Metro has received about 2,300 service calls and made 24 arrests under the new charges, said Officer Jesse Roybal, a spokesman.

Metro, which decentralized various investigative operations last summer, does not have a dedicated squatter squad. Some people say the police could be rounding up far more squatters, though UNLV criminologist William Sousa said it was difficult to gauge whether the arrest tally — comprising 1 percent of service calls in that period — was large, small or somewhere in between.

There might be numerous calls for the same house; some calls might be for people who in fact aren’t squatters; and officers might resolve a call without arresting anyone, said Sousa, director of UNLV’s Center for Crime and Justice Policy.

Sousa wasn’t aware of any research on squatting, but anecdotally, he has “heard some real horror stories out there.”

The housing industry knows them all too well. Real estate agent Keith Lynam, president of the Greater Las Vegas Association of Realtors last year, said he’d heard about squatters “if not every other day, every week.”

Broker Jim Hastings, who specializes in bank-owned homes, wrote in support of AB 386 that many clients had properties that were “seized by squatters.”

One property, near Boulevard mall, would get broken into every week. In one house in the northwest valley, there were drugs, gang members wanted for murder, and a 3-year-old child inside. And in the southwest, lenders fixed up a squatter house but “new squatters moved in before we even had time to inspect the repairs,” Hastings wrote.

Tod Wever, owner of Real Property Management Las Vegas, figures the problem eased as the market regained its footing. But he’s seen vacant houses valleywide get hit by squatters and vandals.

“We’ve had too many stories to count,” he said.

In 2009, for instance, Wever was hired to manage a presumably vacant house in North Las Vegas. He showed up one night to inspect it, but the home was trashed and it looked like someone was living there. He also found an amateurish, fake lease in the house.

Four or five “scary looking guys” came in and confronted him, saying the house was theirs. Wever tried to stay calm, telling them Wells Fargo owned the home, a locksmith was coming and they had to leave.

Wever called the police and sat outside in his car. As he waited for officers and the locksmith, the squatters threw rocks toward his car.

• • •

By all accounts, it seems fairly easy for squatters to find a house.

They can drive around the valley and spot signs of abandonment — dead trees, boarded-up windows, blue-taped foreclosure notices, padlocked doors. They can search property records online to find homes that were repossessed by lenders or hit with liens and default notices. They hear about homes from other squatters. Or they can log on to Craigslist, where people list vacant homes for rent that aren’t theirs to lease.

Some squatters move their families and belongings inside; others are solo vagrants looking for shelter; some cluster with groups of people. Overall, though, squatting can be a “money-making thing” for black-market entrepreneurs, Wever said.

Horizon Realty Group broker Tony Keep once busted a woman with wigs, outfits, tools and business cards with aliases. The equipment let her change the locks — and her looks — and pose as a listing agent.

“She could be Rhonda one day and Gail the next,” Keep said.

For electricity, squatters can set up accounts with NV Energy or clamp jumper-cables to a utility box. Water service can be tougher to come by, said Metro’s Malcolm Napier, who targeted squatter homes with Martinez and pushed for the new law.

In some of the “worst” houses, squatters use pool water to flush the toilets, said Napier, now an internal affairs detective.

Some homes have gone up in flames when squatters cooked food, set fires to stay warm or fell asleep while smoking, Las Vegas Fire & Rescue spokesman Tim Szymanski said. Such fires have occurred in neighborhoods across Las Vegas and nearly all appear accidental, he says.

“They’re living in a building for free, and they don’t want to mess up a good thing,” Szymanski said.

Some get comfortable in their new digs. Vandana Bhalla, a broker and property manager with Signature Real Estate Group, put a for-lease sign in the yard of a presumably empty house in the southwest valley last year. A woman living there, however, called to complain that there was no air-conditioning.

“I said, ‘That’s interesting; I don’t have a lease from you, either,’” Bhalla said.

Squatters break in through windows, crawl through doggy doors or arrange to visit a house with the actual listing agent and unlock a door or window to get back in, according to Wever.

It’s also common to pay someone a few hundred dollars for house keys and a fake lease, something to show cops or real estate agents if they come knocking. Some squatters report meeting with their supposed landlords at a convenience store and paying their rent in cash, police say.

Details of their “rental agreements” can be dubious.

Last year, police found two squatters in a two-story, six-bedroom house near the 215 Beltway and Ann Road in northwest Las Vegas. According to Napier, the squatters claimed to have paid someone almost $132,000 in cash to live there.

Inside, officers found a mattress and practically nothing else.

“If you’ve got, apparently, $132,000 to rent the place, you should be able to afford furniture,” Napier said.

Police also found that the back door had been kicked in, a window had been broken, and that someone had damaged the locks.

• • •

As foreclosures, bankruptcies and layoffs swept the valley, residents lost their homes to lenders or simply abandoned them, emptying subdivisions.

Squatting is neither new nor unique to Las Vegas. But given the volume of empty houses and the valley’s transient population, “we are really prone to it,” said Lynam, of GLVAR.

That also means homes are prone to getting trashed.

Paige Gordon, who lives near Las Vegas National Golf Club, is across the street from an abandoned house that’s boarded-up, filled with garbage and a magnet for squatters.

Wooden planks, bags of rotting fruit, and other trash covered the floor of a room on a recent visit. Broken drywall and insulation spilled out of massive holes in the walls. The kitchen ceiling, or at least part of it, was ripped off, and a backyard utility box was pried open.

Investors bought the house in spring 2007 for $340,000 and flipped it two months later for $465,000, but the home was abandoned in 2011 after the market collapsed. The beat-up house is listed for $200,000 — marketing photos online show heaps of garbage inside and extensive damage — and a sale reportedly is in the works.

It’s not the only squatter house in the area, and Gordon said she was thinking of building a secure entry to her front door.

“It is scary,” she said of living near an abandoned home, “but I have two big dogs” — pit bulls, to be exact.

• • •

Squatter-prevention tips

Step 1: If you believe squatters moved into a vacant house in your neighborhood, call the police.

Step 2: Don’t confront the new residents over whether they have the right to be there.

Step 3: Notify the abandoned home’s rightful owners (if you can locate them) or listing agent (if there is one) that people moved in.

Step 4: Be on the lookout for any signs of activity at a house you know is abandoned — for instance, windows are now broken, different cars come and go, people walk in and out at random hours of the day.

Step 5: Exchange your phone number and email address with neighbors and alert them to suspicious activity at the abandoned house.

• • •

What else is needed to crack down on squatters?

Nevada Assemblywoman Victoria Seaman, a sponsor of last year’s anti-squatter bill, says the law was “a great start” but that more can be done. For example, Seaman plans to reintroduce a bill that would help take homes in foreclosure out of limbo and onto the auction block. Under state law, for instance, a pending foreclosure sale must be canceled if it doesn’t take place within 90 days of the notice of sale being recorded. Seaman’s Assembly Bill 282 would have stretched that time limit to one year. The bill apparently wouldn’t have sped up foreclosure sales, though perhaps it could have helped vacant houses find new owners. “When you have properties sitting as long as you do, squatters know it,” she said.

In a northwest Las Vegas cul-de-sac, Tina Cabrales knows all about squatters — and the difference a new law can make.

She lives next to a house that had squatters both last year and a few weeks ago, near another that had squatters in 2014 and, she thinks, another that had squatters as of a few months ago.

One night last August, the lights came on upstairs in the vacant house next door. Cabrales introduced herself to the new neighbors, four people in their 20s and 30s, the next day. They had arrived in a few cars, though Cabrales never saw a moving truck.

The squatters didn’t make noise, but neighbors got scared. Kids who normally played outside stayed indoors. Cabrales’ children slept in her bed, and the single mom thought about staying with them at her parents’ house.

The police had told neighbors they’d have to wait until the new law took effect, presumably before the squatters could be tossed. At least one person inside, however, was on parole or probation, and officers cleared the house.

The squatters were there only about a week, Cabrales said, but it was “a week too long.”

“When they did actually come and finally do something, they were great,” she said of the police. “Before that, it was basically, ‘Sorry, our hands are tied.’”

Before the new law, police say, there wasn’t much they could do about squatters.

Authorities could charge them with trespassing or lodging without the owner’s consent, both misdemeanors. But overall, squatting typically was viewed as a landlord-tenant dispute to be hashed out in civil courts, and at least once, squatters obtained court approval to stay put, according to police.

Metro Lt. Nick Farese, of the Northwest Command, said squatting was a “gateway” to bigger crimes, but police “didn’t have an effective law on the books” with which to charge people, and squatters knew that.

“There really was no organized law-enforcement response, in no small part because there was no law,” Las Vegas City Councilman Bob Beers said.

Assemblywoman Seaman experienced this firsthand — while working on the squatter bill, no less.

She flew home last year during the legislative session for some real estate work, and when she stopped by an underwater house in southwest Las Vegas that she was trying to sell, she found squatters inside.

They claimed to have leased the home from someone through Craigslist, and that they met at a casino every month to pay their rent in cash.

Seaman persuaded them to move after saying she was a lawmaker trying to pass an anti-squatter bill. But before that, she called Metro Police, who told her they couldn’t do anything.

“It was so ironic,” she said. “There was nothing Metro could do. Nothing. You felt so hopeless.”

Napier and Martinez joined a community oriented policing unit in Metro’s Northwest command around spring 2014. They spoke with Metro’s intergovernmental team about squatters, and after lawmakers introduced AB 386, Napier went to Carson City with other Metro officials to testify about the bill.

Farese acknowledged the arrest tally so far wasn’t “huge.” He said one issue was training, as police have been taught “forever” to treat squatting as a civil issue. But he also compared squatting to identity theft, as both require authorities to verify claims before making an arrest.

He confirmed that there was talk about setting up a dedicated squatter squad, but amid staffing shortages and Metro’s focus on violent crime, it won’t happen anytime soon.

“You can make an argument for a team, but it’s a wish, not really a need at this point,” he said.

Police aren’t likely to ever rid the valley of squatters, with or without a dedicated unit. But when officers find them, there’s often a cocktail of other problems in the house, ranging from guns, drugs and stolen cars to pimps, prostitutes and child abuse.

• • •

If you're in search of legal housing

For people in need of long-term, stable housing, one place to turn is the Southern Nevada Regional Housing Authority. The agency administers federally backed housing vouchers to pay a portion of people’s rent. The SNRHA says it helps provide housing to about 38,000 people under the program. For more information, call 702-477-3100 or visit snvrha.org.

Retiree Joe Biedenbach has lived on Wedlock Lane for about 20 years. A few years ago, after someone broke into a community mailbox, he reviewed footage from his home security cameras to see who did it.

“That’s when I started noticing all this (expletive) activity over there,” he says.

The activity was at 7709 Wedlock Lane, a house across the street that had been empty for a few years. He saw that cars would pull into the driveway and flash their lights, and then the garage would open. He’d also see several boxes of trash outside every Monday and Thursday.

Biedenbach says it became vacant after the owner died. County records show the title wasn’t transferred, and liens piled up for unpaid sewer and garbage bills and homeowners association dues.

Squatters moved there in spring 2013, Biedenbach says. He called the police about it one day, and the next morning, a man showed up at his door. As Biedenbach tells it, the visitor said he was with the FBI and showed him a picture on his cell phone. The man in the photo, Biedenbach says, had tattoos across his forehead.

Biedenbach, who had met the tattooed man at a community mailbox, offered to show his surveillance footage to the visitor.

The man in the photo, apparently, was Bayzle Morgan. He was arrested outside 7709 Wedlock on May 30, 2013, police reports show, and he filled out court paperwork indicating he was broke. He wrote that he was not employed, put an “X” in the space for monthly earnings and answered that he had no money in bank accounts.

But when asked his monthly rent or mortgage, he wrote what appears to be either “$599.99” or “$699.99.” Asked his address, he wrote: “7709 Wedlock Lane.”

Nearly a month after his arrest, Morgan was indicted for allegedly stealing a Suzuki motorcycle at gunpoint. The alleged stick-up occurred May 27 a mile from Wedlock Lane, and police say they found the motorcycle in the garage at 7709 Wedlock.

The same day as that indictment, Morgan also was charged with murdering 75-year-old Jean Main on May 21, 2013. Authorities say Morgan’s blood was found at the crime scene. Prosecutors are seeking the death penalty.

Now incarcerated in High Desert State Prison after pleading guilty to a firearm-possession charge, Morgan is scheduled to go to trial for Main’s murder on Aug. 29. The motorcycle trial is set to begin June 27. He has pleaded not guilty in both cases, his attorney Dayvid Figler said.

In a court filing, Figler said the house on Wedlock was “arguably associated” with his client. When reached to comment for this report, he strongly disputed the notion that Morgan, now 24, was a squatter.

Figler said “at best you have someone who felt he was legitimately staying with someone for a few days.” And Metro, which cited Morgan in a presentation to support AB 386, has “zero proof” that Morgan was squatting. Figler said the police included Morgan’s booking photo in the slideshow because he has “a scary face.”

Figler also denied a request to interview Morgan.

“I’m not gonna help the state execute my client by making him a bogeyman in the community,” he said.

The Sunday asked Metro’s Roybal to speak with someone about Morgan’s inclusion in the slideshow but didn’t hear back.

When Main was killed, Morgan was staying at 7709 Wedlock with four people — his ex-girlfriend Monica Baca; an unmarried couple, Steven Dooley and Kenna Higgins; and that couple’s 4-year-old son, according to grand-jury testimony by Baca and Dooley.

Baca testified that Morgan stayed there for about a week. Dooley moved to the house about three weeks before Main was killed, and he testified that Morgan arrived perhaps “right after” he did.

Dooley testified that on May 22, Morgan “looked like he was really upset about something.”

When they talked about it, Morgan didn’t give details, and Dooley didn’t ask.

“He had said that something went wrong, and that was it,” Dooley testified.

Investors acquired the house at 7709 Wedlock in late 2014 through foreclosure and rented it out.

Despite the squatters and crimes, at least one positive outcome came from the home: It has “brought all the people together,” Biedenbach says.

Neighbors look out for each other, he said, but “it’s just too bad it takes something like that to do it.”

• • •

Squatter-related service calls made to Metro police in 2015

Where there are empty houses, there tend to be squatters — and empty houses are everywhere in Las Vegas. This map shows the number of calls that officers in Metro’s various area commands received last year.

When squatters move in: Two stories from the Desert Shores neighborhood

• A squatter house in this northwest Las Vegas neighborhood was the site of two shootings last year, neighbors said. The two-story, 3,700-square-foot home sold in early 2004 for $330,000 and was flipped 10 months later for $500,000 to a buyer who moved out and filed for bankruptcy. On a recent visit, the front yard was covered with leaves, the front doors were damaged and the locks appeared to have been changed. The front yard also was still decorated for Halloween almost six weeks after the holiday weekend, when a birthday party hosted by the squatters drew a couple hundred people. The party spiraled into a 4 a.m. shooting that struck a few nearby homes and left dozens of shell casings. No one was injured, neighbors said. At another point last year, according to neighbors, a set of former squatters came back to find that others had taken over. “Squatter A shot at Squatter B,” neighbor Jeff Raithel said.

• When squatters took over a house 1 1/2 miles away, different people came and went throughout the day, including women with children and grocery bags. Police later found drug paraphernalia, and child-protective services was called, neighbor Kalif Gordon said. The owners, who filed for bankruptcy last fall, bought the two-story, 2,084-square-foot house in 2004 for $270,000, records show. They packed up and left after the husband lost his job, a neighbor said. Around the time of the bankruptcy filing, a dead bird lay on the ground beneath a dying tree in the front yard. A window near the padlocked front door was broken, other windows were boarded up and overgrown trees made the backyard look like a rain forest. “What you see now is probably the worst of it,” a neighbor said, “because it continues to deteriorate.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy