Courtesy of MANICA Architechture

An artist’s illustration of a stadium on Russell Road and Las Vegas Boulevard was revealed during a Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee meeting at UNLV Thursday, Aug. 25, 2016.

Wednesday, Oct. 5, 2016 | 2 a.m.

It’s fairly common for the public to chip in tax dollars to build a football stadium.

Over the past decade, taxpayers in Minneapolis, Atlanta and Arlington, Texas, have ponied up hundreds of thousands of dollars to build billion-dollar stadiums for their Minnesota Vikings, Atlanta Falcons and Dallas Cowboys. Las Vegas is poised to become the next host city of an NFL team, with the aim of luring the Oakland Raiders.

One thing sets the Las Vegas stadium proposal apart: the size of the ask from the public. Developers behind the project have proposed that the public foot $750 million of the expected $1.9 billion bill. If the public doesn’t, developers have said the deal is off.

Nevada lawmakers are expected to consider the NFL stadium proposal at a special session in the coming days. Gov. Brian Sandoval has said he plans to call the Legislature into session sometime between Friday and Oct. 13 to consider the stadium proposal, as well as a plan to expand and renovate the Las Vegas Convention Center.

With the future of the stadium hanging in the balance, here’s a look at some other NFL stadium projects in the last decade or so, including a breakdown of the financing.

-

AT&T Stadium

Team: Dallas Cowboys

Seating capacity: 80,000

Year opened: 2009

Public contribution: $473 million

Private contribution: $727 million*

Total cost: $1.2 billion

Public/private split: 39% to 61%

*Exact private contribution figures were not available from the city of Arlington. The amount was estimated based on the total cost and the public’s contribution.

The details: In 2004, voters in the city of Arlington approved bonding up to $325 million for the stadium, backed by a half-cent increase in the city’s sales tax, a 2 percent increase in the hotel-motel tax, and a 5 percent increase in the car-rental tax. A second group of bonds, totaling $147.9 million, are backed by ticket and parking taxes. The city of Arlington projects it will pay off the AT&T Stadium debt early — in 2021 instead of 2034, the bonds’ original maturity date. Land acquisition costs were $112 million for the stadium. The Cowboys pay Arlington $2 million a year to use the stadium and $500,000 a year from the team’s naming-rights deal with AT&T (both of which go toward paying down the bond debt).

-

MetLife Stadium

Team: New York Giants/Jets

Year opened: 2010

Seating capacity: 82,500

Public contribution: $0

Private contribution: $1.6 billion

Total cost: $1.6 billion

Public/private split: 0% to 100%

The details: New Jersey didn’t grant any direct public subsidies to build the massive stadium, but the facility was built on state-owned land. Plus, the state gave each football team 20 acres for its training facilities and the right to develop entertainment options on 75 acres. The state also kicked in more than $250 million for infrastructure improvements surrounding the new stadium. At the time MetLife Stadium opened, taxpayers still were paying off $100 million in bonds for the old stadium. Because the Giants and Jets paid to build the stadium, they keep all profits generated from it. The teams pay the state sports authority $6.3 million a year in rent and other fees.

-

Levi’s Stadium

Team: San Francisco 49ers

Year opened: 2014

Seating capacity: The regular capacity is 68,500, but it could be expanded to seat 75,000

Public contribution: $114 million

Private contribution: $1.2 billion

Total cost: $1.3 billion

Public/private split: 9% to 91%

The details: The Santa Clara Stadium Authority — a public agency separate from the city but whose members are the Santa Clara City Council — owns the stadium and is responsible for up to $950 million in construction loans to be paid back with revenue from the stadium, including naming rights and the sale of seat licenses. (The $950 million was loaned by Goldman Sachs, U.S. Bank and Bank of America, though the authority only needed to borrow $879 million.) Santa Clara spent $114 million in public funds on the stadium: $42 million in redevelopment funds, $20 million on Silicon Valley Power, $17 million on parking structure revenue bonds, and $35 million from a 2 percent hotel tax increase (on eight hotels near the stadium). The NFL also provided $200 million through the 49ers stadium affiliate, and the 49ers stadium company also advanced the $35 million to be paid back by the hotel room tax.

-

U.S. Bank Stadium

Team: Minnesota Vikings

Year opened: 2016

Seating capacity: The regular capacity is 66,000, but it could be expanded to seat 72,000

Public contribution: $498 million

Private contribution: $608 million

Total cost: $1.1 billion

Public/private split: 45% to 55%

The details: The public’s contribution included $348 million from the state and $150 million from the city of Minneapolis. The state sold appropriation bonds to finance most of the project. The city is using existing hospitality taxes to pay its portion of the bonds, while the state will pay off the bonds through new corporate taxes as well as proceeds from electronic pulltab gambling. The Vikings football team put $608 million toward the project. The Minnesota Sports Facilities Authority owns and operates the stadium, and the authority also oversaw its design and construction. SMG, which operates the stadium, gives the authority $6.75 million per year to build and maintain its capital and operating reserves.

-

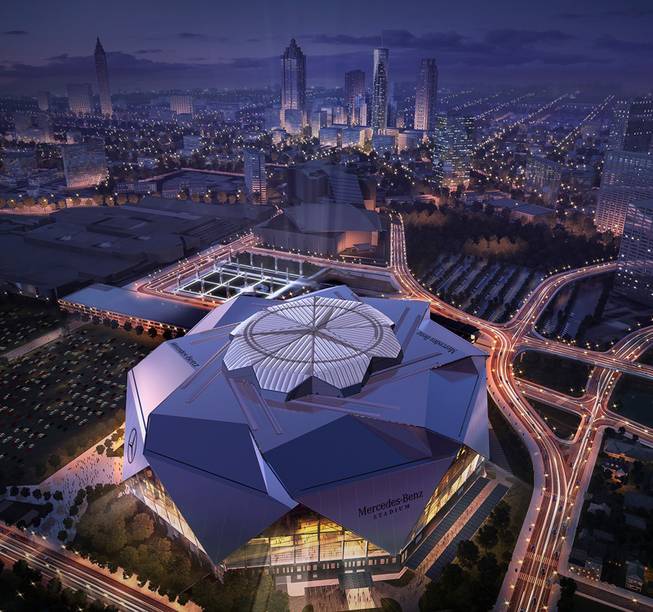

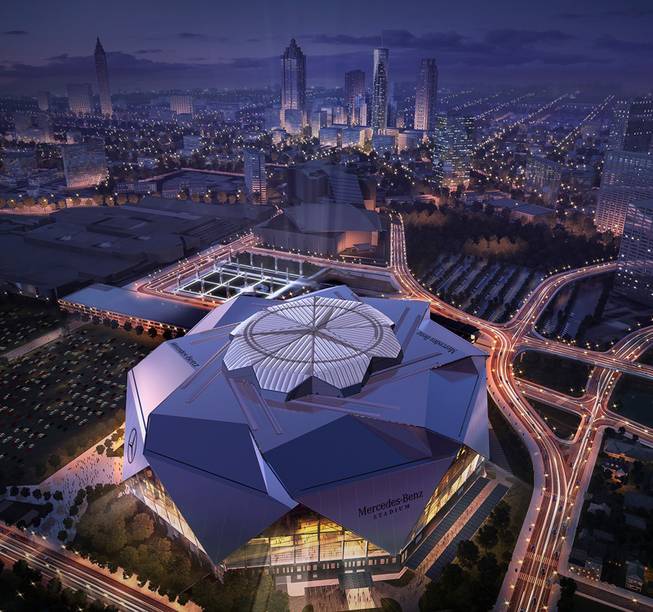

Mercedes-Benz Stadium

Team: Atlanta Falcons

Year opening: 2017

Public contribution: $215 million

Private contribution: $1.3 billion

Total cost: $1.5 billion

Public/private split: 14% to 86%

The details: The state is contributing $200 million backed by an existing Atlanta hotel-motel tax (which was extended for 30 years in 2010), to pay for the construction of the stadium. Local officials said the public also pitched in $15 million for property acquisition, though the stadium is being built mostly on land already owned by the public. The rest will be paid for by private developers. Local media reported recently that private developers secured $850 million in loans and that the NFL will loan the stadium project $200 million. (The state of Georgia is also paying $40 million for parking expansion, however that’s not part of the stadium financing agreement.) The Georgia World Congress Center Authority will own the stadium, and the Falcons ownership group will operate the stadium under a 30-year agreement. The public will receive no share of the proceeds.

-

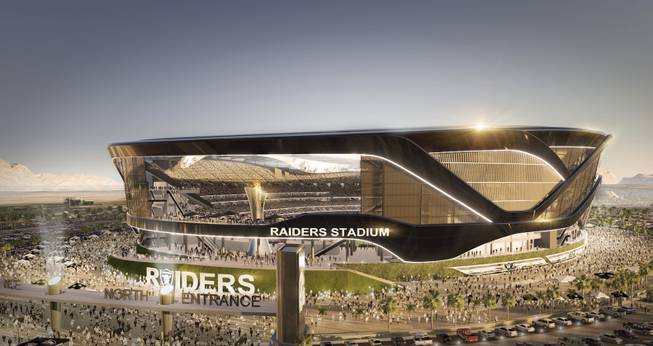

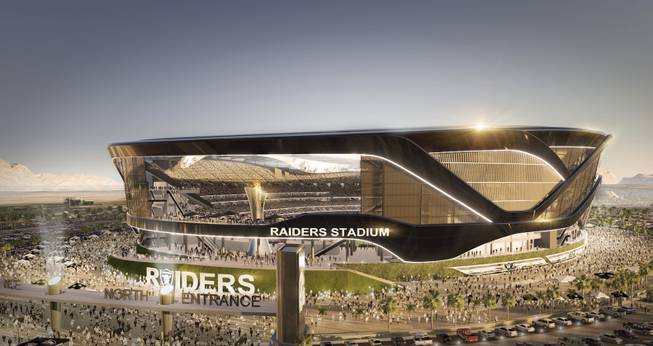

An artist's illustration of a stadium on Russell Road and Las Vegas Boulevard was revealed during a Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee meeting at UNLV Thursday, Aug. 25, 2016.

Proposed Las Vegas stadium

Team: Oakland Raiders (If the NFL grants its relocation request)

Year opening: TBD

Public contribution: $750 million

Private contribution: $1.15 billion

Total cost: $1.9 billion

Public/private split: 39% to 61%

The details: The proposal heading to Nevada lawmakers has the public contributing $750 million and the Raiders pitching in $500 million. Las Vegas Sands Chairman and CEO Sheldon Adelson, who originally proposed the project, has said he will cover the other costs. If the stadium costs $1.9 billion to build, that means the developers would contribute about $650 million. The exact price tag of the stadium itself is unknown. If the project ends up under budget, the developers could wind up paying less than $650 million, narrowing the public-private split. However, the developers are expected to pay for off-site infrastructure, which likely will bring the total project cost close to $1.9 billion. The proposal also does not include a provision to share profits with the public, meaning developers would reap all revenue generated by the stadium. A public stadium authority would own the facility, but it would be operated by a private company.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy