Thursday, Sept. 8, 2016 | 2 a.m.

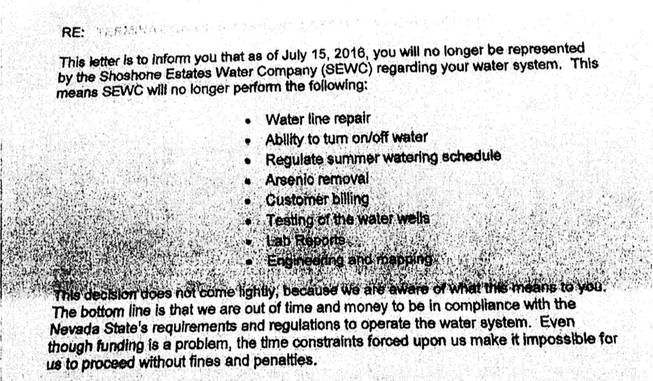

On the day Shoshone Estates Water Co. dissolved in mid-July, the rural Nevada utility sent out an ambiguous letter to its roughly 80 customers. Its Board of Directors wrote: “We are sorry that we do not know the fate of your water system. But, please know that every alternative has been exhausted.”

The board’s rare move to walk away from the Round Mountain nonprofit on July 15, after struggling to fulfill environmental mandates without raising rates, was swift. State agencies stepped in later that day, tapping into emergency funds to keep water flowing while regulators consider a long-term solution. Round Mountain is a community about 50 miles north of Tonopah in Nye County.

As the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada considers asking a court to put the Round Mountain utility into receivership, its future remains uncertain, which highlights the difficulties of managing small water systems that is within the purview of tight regulations at the state and federal levels.

“I don’t know (the future),” Ann Berg, a former Shoshone Estates director who relies on the system for her small business, said after being asked to speculate on the fate of the water company. “I wish I did.”

Shoshone Estates, a nonprofit cooperative, dissolved after the board exhausted several options to secure the funds necessary to bring arsenic levels in drinking water in compliance with federal standards, Berg said. The system, out of compliance for years, was also facing an Aug. 1 deadline with state regulators.

Although regulators for the utilities commission applauded the volunteer board of directors for leaving the system in a position to continue operating, they are concerned about the risks poised by dissolution.

“If a pipe breaks, if a pump fails, or if any water-related operational expense occurs, at this time (the utilities commission) is unsure how any repairs would be financed in order to keep the water flowing and provide reliable water service,” staff for the utilities commission wrote in an August regulatory filing. “Further, the Shoshone Estates system still has outstanding arsenic issues which must be addressed.”

The three-member utilities commission will consider whether to seek a court-appointed receiver to oversee the company’s management and operations, while guiding it toward a resolution with its arsenic issues. Should the commission sign off on the receivership action, staff counsel Tammy Cordova said the court would appoint a receiver to run the utility, a temporary setup that could last from months to years.

“The critical question then becomes, who is the receiver,” Cordova said.

Although there are small water utilities across the state, regulatory staff for the commission said that many water companies threaten dissolution but that few actually follow through. Bankruptcy is more usual.

Compliance issues have dogged Shoshone Estates for years. Before members of the board assumed their positions in 2010, a private owner ran into similar issues. The arsenic levels had become a problem for the system in 2001 when the Environmental Protection Agency adopted stricter rules for drinking water.

The agency replaced a standard of 50 parts per billion with a standard of 10 parts per billion. Since the arsenic level in Shoshone Estates’ supply was over 25 parts per billion, the system was forced to rein in the presence of the chemical, which over many years can cause health problems, including skin damage and increased cancer risk. But the operators had a problem: how to fund the cost of compliance.

“Operating a public water system is one of the most heavily regulated businesses that exists because it’s drinking water,” Oz Wichman, Nye County Water District’s general manager, said in an interview. “Now all of the sudden you’re sitting there with a compliance issue with a very limited revenue stream.”

Until 2010, when the board of directors took over as a nonprofit to address the naturally occurring arsenic in the system, the small utility was privately owned. Though the board was able to secure about $22,000 in community funding for preliminary treatment, it was ineligible for a grant that would have allowed it to proceed with curbing arsenic levels by an Aug. 1 deadline, prompting its dissolution.

“They were very close to moving ahead,” said Cynthia Turiczek, a water engineer for the commission.

In a filing, regulators for the commission argued that receivership could make the water system eligible for federal or state funding to treat the water. Building on a pilot study, the board had planned to deal with arsenic by installing a $500 to $700 treatment system at each of the roughly 80 residences on the system.

Until then, the Nevada Department of Environmental Protection advises residents to reduce exposure to arsenic by purchasing bottled water for drinking, though it claims water is safe for cleaning and bathing.

According to the Nevada Rural Water Association, there are several small water systems near Shoshone Estates. The association has told the commission it hopes that the system will stay under local control.

“There are people in the community who are interested in forming a subsequent entity,” said Executive Director Bob Foerster. “We are trying to help them coordinate that and go down that path as well.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy