A statue of Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump at the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign on September 13, 2016. The installation — which has popped up across the country since mid-August — was masterminded by activist collective Indecline and created by local artist Joshua Monroe, aka Ginger.

Monday, Sept. 26, 2016 | 2 a.m.

Does the First Amendment protect protest art?

You have the right to expression, but not to damage public or private property. Altering billboards or painting murals or putting up statues of birthday-suited politicians in public places can land you charges as minor as permitting violations, or as major as felony vandalism.

Influential artists

Keith Haring’s joyous New York works in the early ’80s — forever immortalized in the cover art to the quadruple platinum 1987 compilation “A Very Special Christmas” (“Christmas in Hollis,” represent) — began to focus on AIDS activism in the latter part of the decade. Haring died from complications of the disease in 1990.

There’s this famous picture of Claude Monet in his studio in Giverny, France, where he’s standing next to a busted old couch, a tiny island leagues away from these massive, sweeping paintings of water lilies. A skylight ceiling reaches up maybe 40 feet like you’d see in a high-rise hotel lobby. And the paintings wrap around Monet like he’s in the front row of an Imax theater, a sturdy man dwarfed down to a 5-year-old trying to sit at the grown-ups’ table.

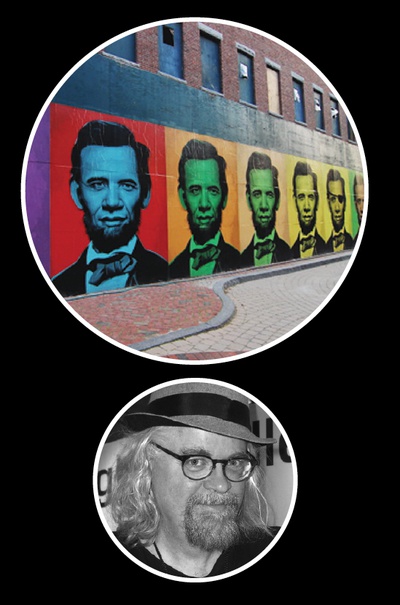

Ginger doesn’t have that problem. His defining work could fit on Monet’s couch, though the shadow it casts might cover the planet.

Ginger is the nom de guerilla art of Josh Monroe, a 36-year-old Cleveland native who has been in Las Vegas since 2012, when he came out to help open the Strip’s dearly departed year-round haunted house Goretorium. He’s also the most buzzed-about artist of the election cycle since, on Aug. 18, five statues of a naked Donald Trump with a tiny penis and no testicles went up simultaneously in five cities across America. It was, perhaps, the signature moment for politically motivated micropenis art in American history.

Monroe lives in a nondescript house in an older neighborhood in east Las Vegas. It’s not a big space, but it’s all the smaller for the giant mold in the middle of the living room being prepped for the next round of Trump statues. They were designed by him but masterminded by Indecline, the nationwide underground-art collective of graffiti writers, photographers, writers, musicians and filmmakers that has frequently operated in Las Vegas in its 15 years of very colorful activism.

The original Trump statue — named not-so-subtly “The Emperor Has No Balls” — dominates Monroe’s studio, sharing real estate with monster-movie ephemera and “Lost Boys” posters. The thing is straight-up wrecked. Monroe said it got attacked with a claw hammer for a video posted to news and culture site Uproxx. There’s a sword resting under Trump’s hands, tip at his feet. If they gave out an Oscar for Yuuugest Picture, this is what the trophy would look like.

More than anyone save Melania, Monroe and his cohorts have been living with the Republican candidate for president.

“All of our shins and legs are tore up from that fiberglass mold,” Monroe said, explaining that they keep accidentally kicking it. “I still have nightmares to this day because of the massive amount of stress to get these things done and out there. I still have to wake up and remind myself this really happened.”

Monroe is something of a surrogate father to the world’s most disconcerting baby. Indecline had the concept for the installation, the plan and the manpower to pull it off. They just needed someone with enough experience in grotesquerie to bring it to life. He had a friend in Cirque du Soleil who had friends in Indecline and made the connection. Monroe admits he took the assignment to get his name out there, and that he had been considering voting for Trump until the candidate mocked a reporter with disabilities at an appearance. That set Monroe off, as he has relatives with disabilities.

Which brings us to our first conundrum: Is a protest object of art still a cry of dissent if the sculptor is initially ambivalent about the message? Or is this, like even the most auteur-driven films, simply a collaborative effort, in the way that “Citizen Kane” would still be “Citizen Kane” if Joseph Cotton were an America-first jingoist who wanted nothing more in life than to lock up that skrilla?

It helped that Monroe wholeheartedly supported Indecline’s vision, even if his motives were more on the “art” side of “protest art.” For the sake of argument, let’s file this under “consistent artistic vision of dissent.” So then the question becomes: Is this effective as a form of protest?

The Trump statues went up — and promptly were taken down by local authorities — in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, New York and Cleveland. It was New York that turned them from a fleeting shred of viral cool that your more Facebook-argumentative friends might have posted to a full-blown moment of point-and-laugh catharsis for some, when the New York City Parks Department issued a release on the Union Square installation: “NYC Parks stands firmly against any unpermitted erection in city parks, no matter how small.” (Come on, give it up. That is the “Eddie Murphy Raw” of municipal department public statements.)

But aside from the Cleveland statue, the other four were in states that are Democratic strongholds where there’s little chance of a Trump victory.

“When we chose the five cities, that was a big conversation. On one end you’ve got longevity. What do these statues have in terms of shelf life if we stick these in front of a courthouse or in front of Trump Tower? Are we killing ourselves for something that’s going to have five minutes of shelf life? Or do we take advantage of it being the 21st century and knowing the second this thing gets the tarp pulled off, everyone’s going to be pulling out their phone?” an Indecline spokesman said on the condition of anonymity, which is key to the group’s ability to engage in illegal stunts for the sake of its message. “And do we put it in an area that’s going to be maybe a little more anti-Trump, a little more hipster, and do we gift it to those areas knowing those are the areas that will make it viral and from there our message can spread and do its thing? For us, it’s like (Trump supporters are) going to see it anyway. And they’re going to see it in a way that hurts them so much more when it’s all over the international media and in their face. The five to 15 minutes it would have run in Kansas or wherever, it doesn’t justify it.”

In this battle between candidates polling with some of the highest unfavorable ratings ever, FiveThirtyEight.com, the gold standard in election forecasting, has consistently shown America likes Trump even less than Hillary Clinton. While he’s currently ahead of or tied with Clinton in three major polls, FiveThirtyEight routinely assigns the GOP contender only a 30 to 40 percent chance of winning. The day the statues went up, the site gave Trump only a 23.8 percent chance. So there’s an element of protesting against him that’s like protesting a chilly Vegas day in September. It could happen. It’s just not terribly likely.

“It’s a real threat. I don’t want people to think it’s OK to just not care. I think it’s really important in the next two months to do whatever you can to diminish this guy, or fight against him. As we learned with Bush, elections can be stolen. It’s not worth it to me to be like, it’s in the bag,” Indecline’s spokesman said. “Trump has this little role he plays that seems to resonate with people, but when you look at those people, good God, it’s scary. He’s abrasive and he’s disgusting, and the things he says are completely inappropriate. He’s every definition of bigot and tyrant that you could assemble, but I think what pisses me off the most is he’s got this following. It’s that susceptibility, that mentally malleable populous that can fall for (expletive) like him.”

Two more Trump statues went up Sept. 14, one in Miami and the other overlooking the Jersey City road to the Holland Tunnel. This time it was legal. Art collector Moishe Mana worked with Indecline to install the Ginger-made pieces on properties he owns. The Miami installation was originally placed atop a billboard until police begged Mana to take it down on the grounds that it could cause traffic accidents due to gawkers. Mana moved it to the rooftop of a building he owns in the same neighborhood, and that statue will stay in place until the election. The Jersey City specimen lasted all of five days before it was stolen — something Indecline predicted would happen after one of the original statues showed up at an auction in Los Angeles.

And right around midnight Sept. 21, the Wednesday before the Life Is Beautiful festival was set to start in downtown Las Vegas, naked Trump made an appearance for the home crowd. The roped-off statue was installed in a parking lot on Sixth Street and Carson Avenue. The plan called for it to be moved around during the festival, but vandals apparently had other ideas. Between Thursday night and Friday morning, they brought the statue down, covering it in graffiti and leaving two sad feet clinging to the base.

• • •

Danger is part of the appeal of underground art. The artist is risking fines, jail time and the raw embarrassment of being nicked in the act. There are real repercussions, though. Charges were filed over the Trump statue in San Francisco, claiming $4,000 in damage to public concrete. In Rochester, N.Y., activist Beth Wittenberg was recently arrested for painting a Black Lives Matter mural on state property. And Brian Whiteley, who put up a Trump tombstone in Central Park, earned himself a visit from the Secret Service.

Speaking of New York, in 2012, artist Takeshi Miyakawa decorated the city with LED-lit plastic bags and was rewarded with charges of reckless endangerment and planting a fake bomb. And in the same city in 1974, co-founder of the Guerrilla Art Action Group Jean Toche got into trouble with the FBI thanks to fliers calling for museum curators to be kidnapped. This year, when evolutionary biologist Steven Le Comber wanted to prove the usefulness of geographic profiling, his case study was famed British provocateur and street artist Banksy. Crime is component. This is the art of vicarious rebellion. But another big part of the equation is surprise.

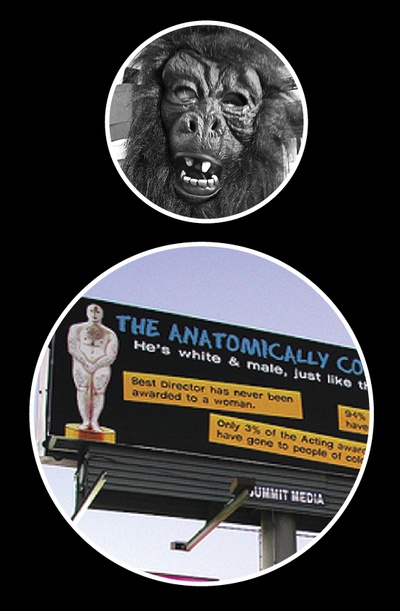

Los Angeles street artist Plastic Jesus has surprised Oscars Week visitors to the Hollywood Walk of Fame with large gold statuettes, maybe on a stripper pole (protesting sexism this year) or on all fours snorting drugs (protesting celebrity addiction last year). One of his calling cards is a giant, rolled-up bill of American currency flanked by equally oversized rails of cocaine.

He’s doing his part to derail the Trump Train, building a tiny wall around The Donald’s star on the Walk of Fame and posting “No Trump Anytime” parking signs around L.A. The Trump statues, as powerful as they are, are somewhat diminished in legality and permanence.

“Part of the message is lost,” said the Brit who’s been called the “Banksy of L.A.” about underground art’s mostly illegal nature. “The fact that your art piece is done without permission, that itself sends out a message. However, once a piece goes global and gets widely viewed, I think that’s often more important. I will use walls with permission if I think the message is strong enough.”

Plastic Jesus, who declined to use his real name, has only been doing this for three years. In another life, he was a photojournalist who covered the wars in Bosnia and Kosovo and the nation-shattering earthquakes in Haiti and Japan. He said the element of danger to street art gave the whole thing a jolt of adrenaline.

Indecline’s spokesman insists the art comes first, but he admits the outlaw thrill isn’t entirely excluded from the calculus. Las Vegas’ devil-may-care character tends to seep all over everything. It makes for fertile ground as a crossroads for underground artists.

A history of artistic rebellion

• 1937: Pablo Picasso paints “Guernica,” one of the most defining and enduring anti-war protest images in art history. Nazis were officially on blast.

• 1974: Tony Shafrazi is arrested in New York for spray-painting “KILL LIES ALL” on “Guernica,” in protest of the release of William Calley, who participated in the My Lai massacre. Shafrazi claimed he was bringing the painting “up to date” and back to life. Jean Toche would be arrested for his fliers defending the incident, calling on museum curators to be kidnapped.

• 1977: The Billboard Liberation Front, one of the earliest practitioners of altering billboards, forms in San Francisco.

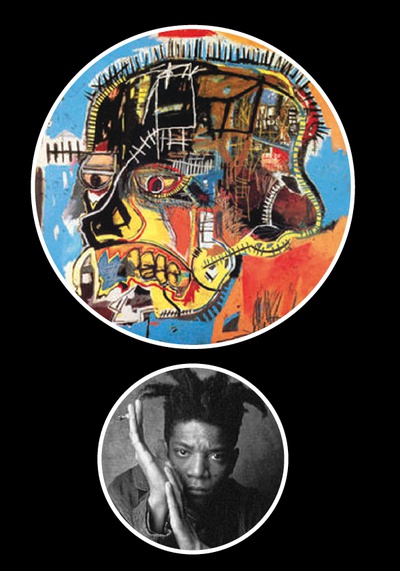

• 1978: The Village Voice brings attention to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s original graffiti collaboration project with Al Diaz, SAMO.

• 1984: Ron English is arrested in Dallas for altering billboards, frequently twisting advertisements into anti-corporate messages.

• 1989: Shepard Fairey creates his “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” stickers.

• 1999: Banksy’s “The Mild Mild West,” showing a teddy bear throwing a Molotov cocktail at police, goes up in Bristol, England, marking the artist’s first well-publicized piece.

• 2008: Fairey debuts his Obama “Hope” poster, which would serve as the campaign’s iconic image.

• 2010: “Exit Through the Gift Shop” popularizes Banksy — and art-hack Mr. Brainwash — with the public.

• 2016: Indecline’s “The Emperor Has No Balls” statues popped up in New York City, Los Angeles, Seattle, San Francisco and Cleveland. A month later, another appeared in Las Vegas on the corner of Sixth Street and Carson Avenue for the Life Is Beautiful Festival. The roped-off Trump was installed in a parking lot around midnight Wednesday. The statue was to be moved around during the festival, but between Thursday night and Friday morning, vandals knocked it down and covered it in graffiti.

Aficionados can read the backs of signs all over the city like a road map of the country. There are more stickers from far-flung artists here, Indecline’s spokesman said, than just about anywhere else.

“Las Vegas has always treated the edgier aspects of culture very well,” he said. “Once you start traveling out in the country or the world, you start looking around and you realize how special Las Vegas is. There’s an inherent rebel nature. It still has that cowboy swagger.”

The swagger is apparent to artists working in the more high-profile Los Angeles media market. Shepard Fairey, the street-art elder statesman whose Obama “Hope” poster is the socially conscious yang to naked Trump’s fire-and-brimstone yin, stopped by Life Is Beautiful to talk about the form. He was among other street artists contributing to the fest’s collection of murals.

“I was quite pleasantly surprised at the amount of art that’s there,” Plastic Jesus said of the downtown Las Vegas landscape. “You’ve got my fellow Brits: Banksy has had a piece there, and D*Face. It’s really good quality art that’s there. Sadly, a lot of people who go to Vegas are overlooking the art, the creativity that’s going on there. ... Vegas has lots of roots in fighting establishment, fighting the government and fighting the normal. Really, it’s a bit of a shame people aren’t more vocal, don’t get more visibility for the street art going on in Vegas.”

On the one hand, you have a town operated in its formative years by the syndicate, a kleptocratic golden age that’s remembered fondly by those who lived it and romanticized by those born too late. On the other, you have an ersatz architectural vernacular. When the most iconic buildings in the city are goofy re-creations, you start to take the idea of mocking things through art for granted.

Once you get used to it, everything in the world becomes fodder for appropriation. In other words, the primordial soup of underground art is built into this city’s bones.

• • •

Indecline exploded onto the national scene with the first edition of “Bumfights,” the 2002 video compilation of, you know, bums fighting. Outcry was immediate and predictable. Subsequent “Bumfights” volumes were produced outside Indecline’s purview, but the group came back with a 2003 video, “Indecline: Vol. 1 — It’s Worse Than You Think,” that showed in uncomfortable, unflinching detail the plight of the mentally ill and street people, but it also veered into chronicling assault in a way that made everyone — perpetrators, filmmakers and viewers — feel complicit.

The rest of the video focused on skateboarding and graffiti, which was spotlighted in Indecline’s “Legalize Crime” videos. Those productions are heavy on graffiti artists tagging under cover of darkness, deploying their personal calling cards or sometimes the Indecline logo of a devil-horned businessman. In 2012, the group offered up “Wheel of Misfortune,” a graffiti project by member artist Aware that took to an abandoned manganese leeching pond southeast of Las Vegas. With planks that read “Lose a Job,” “Lose a Home” and “Lose All Hope,” this one struck a sharply political chord.

Around the same time, “Dying for Work” and “Hope You’re Happy Wall St.” billboards popped up overlooking Interstate 15 near Bonanza Road and on South Highland Avenue. Both featured suited mannequins hanging by their necks.

This election cycle, though, has seen a creative surge from Indecline. Last October the group painted a mural of Trump wearing a ball gag below the words “¡Rape Trump!” along the U.S./Mexico border. (Complete with instructions on how to reach Trump Tower from Tijuana.) In March, it affixed the names of Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and Freddie Gray — black individuals whose controversial deaths are tied to police actions — to the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Next up is a project that focuses on gun control.

“When we finished Trump and we started talking about what the next move is, it wasn’t how do we captivate the world or how do we break the internet?” Indecline’s spokesman said. “It was: What are the issues that we’ve missed while focusing on this (expletive)? It took up six months of our time. We’ve never spent that much time on a project.”

Projects start with an internal discussion about what issues to tackle and what direction a new piece should take. From there, there are 35 to 40 core men and women across the country (and some operating in Europe), typically no more than three to six in any given city, who will execute the mission. Normally, the turnaround time is counted in weeks, not months. But the Trump statues required an enormous amount of collaboration and organization, in a way that was unprecedented since Indecline’s inception.

Along the way, the mainstream seems to have caught up to, if not the message of protest-focused work, at least the aesthetic of street art. Fairey’s 2008 Obama poster and the 2010 Banksy documentary “Exit Through the Gift Shop” were breakthrough moments. And as the renegade form broke through, Las Vegas was right there to capitalize on it.

The value in art

• Shepard Fairey’s work “War Is Over” sold for $71,700. It’s a spraypaint-and-mixed media painting.

• Banksy’s work “Keep it Spotless,” sold for $1.7 million. It’s a spray-paint on canvas conveying his take on ’50s domesticity.

The Cosmopolitan turned its parking garage over to muralists — all major players in the street-art scene — with works by Retna, Stephen Powers, Kenny Scharf, Shinique Smith, Curtis Kulig and Fairey adorning the concrete walls. The short-lived Rattlecan at the Venetian opened in 2013 with a collection of walls done by Defer, Rime, Aiko, King Ruck, Kulig, Invader and others. And works created for Life Is Beautiful have “literally changed the face of downtown Las Vegas, which now doubles as an open-air art gallery,” Vice offshoot Noisey recently reported.

Having art in these spaces is objectively better than the alternative — D*Face’s lovelorn zombie on the side of El Cortez Cabana Suites makes Seventh and Ogden way cooler than it has any right to be. Yet they were all done with permission, or on commission. They’re all positive. On-brand. The only one with a hint of controversy — Ukrainian artist Interesni Kazki’s cowboy with a slot machine in his chest menaced by grasping, disembodied hands on the side of Emergency Arts — was painted over in 2013 for being too negative.

Even the grimiest of revolutionary art has to bow to commerce sometimes. One patron in Oregon has commissioned a Trump statue for his private collection, though the Indecline mouthpiece said proceeds would be rolled into future projects. On its website, the group sells all kinds of branded merchandise, some of it pushing the “Legalize Crime” idea from past projects. This is either brilliant meta-commentary on consumer culture or a deft way to rope impulse control-challenged 17-year-olds into footing the bill. You can fight corporate power all day long, but spray paint doesn’t pay for itself, and starving artists aren’t as much fun when you’re the one starving.

“I was pretty much being a whore. I wanted to get my name out there and ride on the coattails of this,” said Monroe, who has been stalked by major media outlets since the incident, ranging from Rolling Stone and The Washington Post to Newsweek, The Guardian and The Daily Beast. Indecline’s video of his creation of the statues has nearly 800,000 views, and if you search “Naked Donald Trump Statue” on YouTube, it yields over 14,000 uploads. “The only statement I wanted to do was, ‘Hey, look what I can do. ... Give me a job.’ For anybody in any industry to strike gold like this, to be able to hit a home run like this, the idea that you may not hit anything like this, it weighs on me. If I had the opportunity to go do something major, I would jump on it. If I had to commute to L.A. every week, I would do it because I know it would be worth it. If I could finally get paid for doing what I love — any artist would do that.”

There’s love of message and love of the game, whether it’s in the craft or the thrill. Even Picasso’s “Guernica” was initially done on commission, so love of money isn’t out of the question, either. Motives aren’t always clean and intentions aren’t always pure, but a big, naked blowhard and his missing balls? Well that’s funny, or offensive, forever.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy