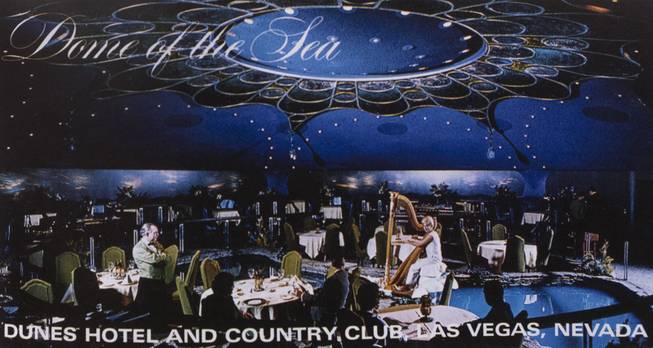

A Dome of the Sea postcard shows a seascape restaurant at the Dunes Hotel. From the book The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream by Stefan Al.

Tuesday, April 18, 2017 | 2 a.m.

Las Vegas has taken a beating from the architecture establishment over the years, with critics characterizing the city’s resorts and casinos as a carnival of flash-over-substance designs — derivative, tacky and disposable.

But the elites who’ve written off Las Vegas as a culturally insignificant freak show have missed the big picture, writes the author of a new book by MIT Press about the history of architecture in the city.

In “The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream,” Dutch architect and urban designer Stefan Al argues that the city’s ever-changing design landscape has reflected decades of important cultural, societal and economic trends. Intense competition for casino visitors drove designers to be especially attuned to shifts in consumer tastes, and to innovate accordingly with a “creative destruction” approach that cycled out resorts that had lost their appeal.

Far from being an outlier, Al contends, Las Vegas has become a model for cities around the globe.

“Las Vegas underscores America’s entrepreneurial spirit to the extreme,” Al says in his intro. “A story of both waste and innovation, of failure and triumph, this book shows how a city tuned to the convulsions of the commodity economy and the fickleness of desire grew from a little desert town into one of the world’s most visited cities. Although the city started as an exception to the Puritanical values of mid-twentieth-century America, it has become a major innovator in today’s ‘experience economy.’

“From self-invention to cutthroat competition to risky ‘casino capitalism,’ Las Vegas is a microcosm of America.”

From there, Al walks readers through the progression of Las Vegas casino design, from the Western-themed “sawdust joints” of the city’s early days, so named because sawdust was sprinkled on the floors to soak up tobacco spit and spilled drinks, through the “star-chitecture” era in which renowned architects created such projects as CityCenter and the Cosmopolitan.

Breaking the city’s architectural history into seven eras, he explains how each one was on the leading edge of cultural trends. For instance, as Americans were beginning to leave inner cities for suburbs in the 1940s and ‘50s, Las Vegas responded with casinos featuring lavish pools, verdant lawns and bungalow-type accommodations. The “Disneyland” era of the 1980s and 1990s came as Disney became the No. 1 entertainment company in the world and amid a cultural shift from the freewheeling 1970s to the more buttoned-down ’’90s.

“The history of the Strip represents the ever-evolving architecture of the American dream,” he writes.

The city’s history is loaded with creativity and unconventional thinking, Al writes, as designers who were far more concerned about appealing to the masses than adhering to traditional architectural tenets competed to one-up each other.

A key example: the “sign wars” of the 1950s and ’60s, when the city came alive with marquees that used miles of neon tubing, thousands of incandescent bulbs and even mechanical features and could be seen from miles away.

“Las Vegas was like an open-air laboratory experiment, with sign designers as uninhibited amateurs scientists weaving tapestries of neon,” writes Al, an associate professor of urban design at the University of Pennsylvania.

While much of the book focuses on design, it’s also a history of the personalities and forces that shaped Las Vegas. But while treading ground that’s been covered in an endless string of books about Las Vegas — Bugsy Siegel, Howard Hughes, Steve Wynn, nuclear testing, the “Disneyfication” era, etc. — Al keeps the book moving with anecdotes and insights that may take readers by surprise.

For instance, Al notes that although Las Vegas didn’t have a strong connection to Western culture when it was settled — the desert environment wasn’t conducive to cattle ranching or farming — it adopted the theme for its early casinos to capitalize on the popularity of Western entertainment and make gambling seem less stigmatic to mainstream Americans. So began Las Vegas journey toward becoming a global leader in marketing.

And while it’s a well-worn part of Las Vegas lore that the Flamingo ran grossly over budget when it was being built by Siegel, did you know that part of the reason for the cost overruns was that Siegel designed an escape tunnel for his apartment at the resort?

Although Al paints Las Vegas in a largely positive light, he doesn’t shy away from some of the city’s more shameful moments. Addressing the institutionalized racism that led to Las Vegas being labeled “the Mississippi of the West,” he notes that Paul Revere Williams, the black architect who designed the Royal Nevada resort, wasn’t allowed into the property.

And in his section on the late 1960s through the early ’80s, Al describes a city that fell into a malaise. As the era of mob ownership gave way to corporate operation of casinos during that time, the designs of the buildings went from flashy to conventional as the hotel companies that owned the resorts adopted the same bottom-line-oriented architecture they used in other cities. Meanwhile, the oil crisis of the mid-’70s indirectly was resulting in neon signs begin replaced by more utilitarian plastic-and-fluorescent-bulb boxes. The reason: Neon signs were perceived to be energy hogs at a time when the public was demanding conservation.

But through the ups and downs, Al says, Las Vegas became a global pioneer in design.

“These days, mob king ‘Bugsy’ Siegel’s ‘build it and they will come’ attitude finds its equivalent in cities’ desperate attempts to build icons that attract tourists,” he writes. “In a world where every metropolis is a competitor for visitors, cities learn from Las Vegas’s continuous reinvention to ‘fix’ their own image.”

The 272-page, hardcover book contains 63 photos and illustrations. It’s available for $34.95 in print and $24.95 as an e-book. For more information, visit here.