Clark County School District (CCSD) Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky delivers his annual State of the Schools address before an audience of educators, students and community leaders to highlight the district’s growth and accomplishments at Valley High School on Friday, Jan. 27, 2017.

Monday, Aug. 14, 2017 | 2 a.m.

What is the 80-20 mandate?

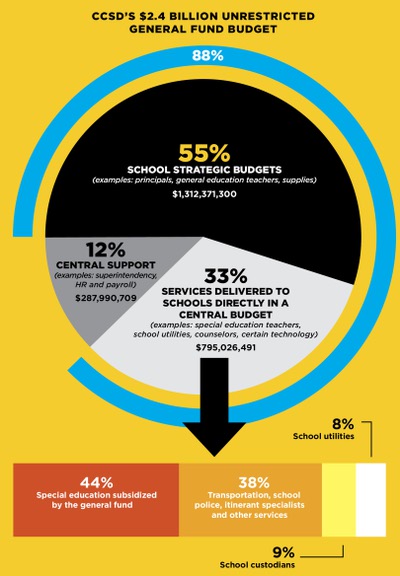

Under the new law, CCSD must allocate at least 80 percent (increasing to 85 percent next school year) of the district’s total unrestricted money — $2.4 billion — to schools for their strategic budgets, giving them greater ability to make and support decisions at the school level. (That “unrestricted” budget doesn’t include federal funding programs such as Title I, capital improvements, performance initiatives like Zoom Schools or a partially weighted funding formula being deployed this year to help disadvantaged students). Based on its own analysis, CCSD already complies with the letter of the law, with 88 percent of its budget directly serving schools. But administrators support the reorganization following the spirit of the law in giving more control to schools.

Students starting classes Monday in the Clark County School District might not notice a change, but the district’s operational structure is going through a massive change — an ongoing effort to shift control from administration to schools.

The shift has been years in the making, with the bipartisan passage of Assembly Bill 469 this legislative session cementing work done by Republican lawmakers in 2015. CCSD Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky said after the new law’s passage that it addressed some of the district’s legal concerns, laid out in a lawsuit the Clark County School Board filed against the Nevada Department of Education and Nevada State Board of Education in late 2016 — and refiled in the spring.

The suit alleged that the committee helming the reorganization “overstepped its authority and failed to complete a required financial impact study while burdening the district with unfunded mandates in violation of state law,” according to the Las Vegas Sun.

Skorkowsky later said it was not the structural changes CCSD leadership feared, but the possibility that a rushed implementation would lead to mistakes and negative effects on students for years to come. The district’s enrollment tops 320,000, the fifth-largest in the nation with nearly 75 percent of the state’s K-12 students in its classrooms.

Implications are powerful.

And the district already was making progress on one of its most dismal metrics. Over the last two academic years, CCSD’s graduation rate rose from 70.9 percent to 74.8 percent. It still lags behind the national average of 83.2, but Skorkowsky is bullish. He said about 19,500 graduates — a record — walked across the stage in June, with summer ceremonies expected to bump that up significantly.

“We are seeing great efforts by our schools to get more kids across the finish line,” he said during an Aug. 7 meeting of the Advisory Committee to Monitor the Implementation of the Reorganization of Large School Districts. It’s a long name for the legislative group overseeing the rollout. On the school level, effects are expected to be felt by the 2018-19 academic year.

The reorganization was conceived as a way to empower schools to drive student achievement and to maximize efficiency and responsiveness to local needs by giving teachers, support staff, parents and community members input on where authority lies and how money is spent. CCSD Deputy Superintendent Kim Wooden said School Organizational Teams (SOTs) representing these diverse stakeholders were launched districtwide last school year to conduct public meetings and help inform decisions affecting their campuses. “The individual schools will address their needs in individual ways,” she said.

It sounds simple and reasonable, but turning a ship the size of this district is a feat, even without the heated politics around improving education in Nevada. Much is still being discussed, but CCSD’s transformation is happening.

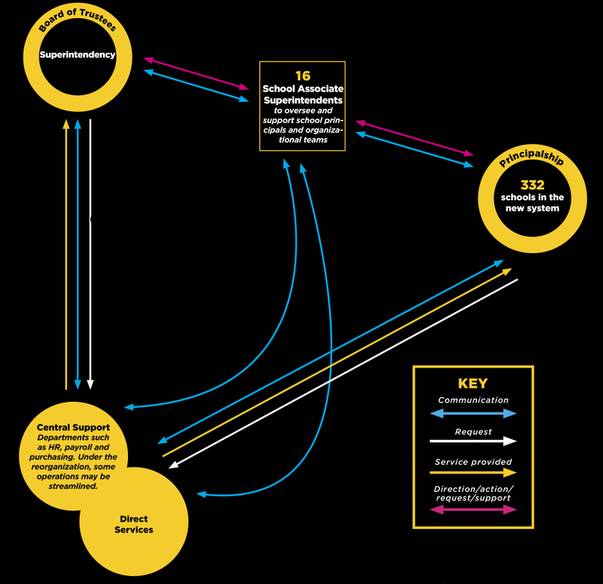

New organizational structure

Mike Barton, CCSD’s chief academic officer, described the district’s old structure as “top-down.” A Nevada legislative committee worked with Canadian academic Michael Strembitsky to create the model below for how authority might flow to empower individual schools. Barton explained that it is not set in stone, though it provides a framework for ongoing discussions of what will achieve the best outcome under the law.

Benefits of new structure:

• Schools would be directed by associate superintendents also advocating for their needs.

• Schools could directly purchase services as needed

• Involvement of stakeholders would likely increase

• Schools would have greater flexibility to make operational and budgetary decisions

Autonomy to decide on services

When will the plan be decided and fully implemented?

The district expects the reorganization to be felt at the school level by the 2018-19 school year. However, so much remains to be decided and tested that no one is certain when fine-tuning will be complete.

About half the principals in the district responded to a June survey about where they saw the biggest need for more autonomy. Discussions are ongoing about which services schools should be able to request and purchase directly, as there are concerns about compliance with state and federal requirements for certain programs and funds. But here are several elements for which decision-making power could shift, potentially affecting the student experience:

Where do school organizational teams fit?

Composed of various school stakeholders, including teachers and parents, SOTs will advise and consult with the principal to make site-based decisions. The public will be welcome at the meetings and able to comment on discussions, though decisions ultimately are in the hands of the principal.

• Librarians

• Counselors

• Teacher-student ratio

• Site-based technicians

• Music specialists

• Special ed teachers

• P.E. specialists

• Humanities specialists

• Fine arts specialists

• Custodians

• Night custodians

• Gifted And Talented Education teachers

• English-language learner strategists

• Special ed-related personnel (psychologists, speech pathologists, physical therapists)

• Instructional Design and Professional Learning Division project facilitators

• Family and community engagement services personnel

• Grounds staff

• School nurses

• English-language learner itinerant testers

• Food-service managers

• Food-service staff

• School police officers stationed at schools

• Bus drivers

Another radical move for CCSD

As the reorganization takes shape, another initiative is shaking things up.

Education reformers have long fought for a weighted funding formula for CCSD, and Senate Bill 178 represents a first step.

The original plan was to prioritize special education students, gifted students, low-income students on free or reduced lunch (FRL) and English language learners (ELL), as they might face more challenges or benefit from targeted programs. The compromise — based on available funding — is only partially weighted, with $1,200 in extra per-pupil funding going to FRL and ELL students in the bottom 25 percent academically in all one- and two-star schools and some three-star schools determined by the state. (Star rankings from 1 to 5 are growth-based from standardized test scores.)

For example, Desert Pines High School has 698 eligible students, translating to $837,600 in new funding. Return-on-investment will be tracked, and SOTs are expected to help determine how the money is applied to maximizing those returns.

“It’s absolutely necessary to launch this work,” said State Superintendent of Public Instruction Steve Canavero. “Only when principals, teachers and School Organizational Teams are granted the autonomy afforded to them under the law and the commensurate funding to act, will we know, will I know, and will the state board know, specifically the challenges that they face.”

How did this initiative come to be?

Assemblyman David Gardner, R-Las Vegas, sponsored AB 394, the original legislation on the reorganization. He said during its first hearing in 2015: “This bill is an attempt to make our school districts more accountable and closer to parents.”

Once a divisive political issue, the reorganization gained support from leaders of both parties this session.

“The bipartisan effort to pass AB 469 and the visual of all the senior leadership in the Legislature appearing together at the table to endorse the bill was incredible, and frankly, may be the single catalyst that allowed the reorganization to get to this point today,” said Community Implementation Council (CIC) Chair Glenn Christenson, testifying during a July meeting. “We need more of that cooperation.”

Sen. Michael Roberson, R-Henderson, chair of the Legislature’s advisory committee on the reorganization, has been its devoted champion. Unique to Nevada, the model was shaped by the vision of Canadian education reformer Michael Strembitsky, who worked with the committee on a plan to manifest his vision of “right-sizing” struggling districts by shifting some decision-making to schools.

Still, Roberson shares the fear continually voiced by Skorkowsky.

“We have to get this right,” Roberson said last fall. “We have to make this reorganization effective.”

A 2015 analysis by the Nevada-based Kenny Guinn Center for Policy Priorities says there are few examples of school districts that have deconsolidated, and no academic research connecting such a structural change to better academic performance. States that have broken down districts include Utah, Arkansas, Delaware and Maine, with unsuccessful efforts launched around large urban districts in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh and Boston. CCSD’s reorganization “mirrors both successful and unsuccessful initiatives,” according to the Guinn Center.

Given the ground being broken, the implementation process will involve plenty of fine-tuning. All parties are currently discussing where authority and funding should be transferred from the district to the schools. The goal is to present options to the school board by this fall, with the board expected to approve a mechanism.

To aid the transition, CCSD was required by the state to hire consultant TSC2 Group for $1.2 million to assist with the reorganization through October. Consultants provided the district with the materials needed to help form and engage with the SOTs, and Skorkowsky said the teams had seven training sessions before kicking off their meetings Jan. 15.

“We are in the process of retraining everybody in the way we have to do business,” he said, “and it is a challenge.”

Growing pains

Bozarth Elementary School teacher and SOT chair Jill Montgomery said strong leadership at her school made the SOT a positive experience. Her biggest struggle was not knowing if all parents were aware of the new structure and opportunity to take part. “Because it’s so new, we didn’t have a high percentage of people coming,” she said. “We only had one parent come to any of our meetings.”

The CIC’s Christenson said such complaints were expected but unwanted. “There is a real need for better internal communication. You go through a reorganization, you’re not going to get it perfect. It’s going to take time to work through these problems,” he said of the journey to give the community “much more influence.”

Yet some teachers and parents believe the SOTs don’t have any real influence, and that backlash is possible if members make unpopular recommendations. Several speakers during the Aug. 7 reorganization update echoed similar concerns, saying they had issues with communication and problem solving, especially when it came to budget discrepancies.

Mesquite resident Courtney Sweeten, who has a 5-year-old starting kindergarten and a 3-year-old going into pre-kindergarten, sits on the Virgin Valley Elementary School organizational team, which she says looked into filing a lawsuit over a $100,000 budget shortfall.

“We simply want regulations to be followed,” she said, “especially now that they are state law, and we want to see our students start the year with the resources that they need.”

The school lost two teaching positions because of the shortfall, pulling from other programs to hire a fourth-grade teacher and starting the year without a kindergarten teacher.

“Our associate superintendent hasn’t been helpful; we don’t know where to go to get this resolved,” said Sweeten, a member of Break Free CCSD, a pro-reorganization group. She noted that the reorganization gave schools the opportunity to improve.

SOT engagement is key, and while Montgomery is hopeful awareness will build, she said the after-school meetings may keep some from participating.

Angela Kozlowski, a seventh-grade English teacher at William H. Bailey Middle School, did not participate on its SOT last year. She said teachers were told to come forward if they were interested, though she didn’t hear much else about the process. Understated recruiting might not be the reason teachers sit out.

“We all have a lot on our plate, and to have another meeting …” she said. “What if you don’t have anyone interested? Then the administration handpicks those people.”

Skorkowsky said the district was beginning to deal with school-specific issues. “That is part of what we have to do,” he said, “which is not only change the budgeting process and the plan of operation; it is changing the entire climate and culture of the Clark County School District.”

How will schools handle new decision-making responsibilities?

If there is a linchpin to the reorganization’s success, it might be the School Organizational Teams (SOTs). The proposed operational structure demands engagement from stakeholders across the educational spectrum, and architects stress the importance of their diverse views, even if administrators don’t follow their advice.

• Who can be on the teams? Teachers, parents, support staff and, in middle and high schools, students can be elected by peers (teachers vote for teachers, etc.) to teams meeting at least once a month to discuss and make recommendations on certain budget and hiring decisions. Newly elected teams must be in place by Oct. 1 of each year, and members serve until Sept. 30 of the following year, though they can be re-elected.

• What do they have a say in? A SOT provides advice to the principal regarding a school’s operational plan. Team members assist in carrying out that plan, though their level of direct involvement has yet to be decided. They can provide checks and balances on the principal’s power by giving input on him or her to the associate superintendent up to two times each school year. (The limitation on this input is meant to push the teams to work out any issues with their school’s leader rather than skipping to the next level of authority.)

What if SOTs disagree with the school principal?

“The autonomies are up to the principals, not to the SOTs, or to anybody else,” said Sen. Aaron Ford, D-Las Vegas. “We heard a lot of expert testimony, and some of that testimony said the No. 1 key to the success of a school was the principal. Not a good teacher, which is what most folks would say, but the principal. ... The autonomy the SOT has is to make a recommendation, is to give advice.”

Roberson agreed that the buck stopped with the principal but emphasized the crucial role of the SOTs. “This is all about vesting the community with real say in the process,” he said.

Thus far, officials, parents and teachers agree that communication could be improved. SOT success depends on school makeup and factors it may be dealing with, said Kenny C. Guinn Middle School SOT member Michele Staron.

“It’s going to be hit or miss depending on where you go to school, who the principal is, whether the principal has a collaborative environment with the parents and staff,” said Staron, who has a seventh-grader and triplets entering eighth grade at the school. “I’m very fortunate in that Guinn was always run in a very collaborative manner,” she said, explaining that committees were informing the school’s budget decisions before the reorganization became law.

Staron said her SOT helped make the tough decision to cut staff when a student shortage put a hole in the budget last year. She felt that being part of the process helped her understand where every dollar went, showing the reality of the school’s limited options. “As a parent, if you didn’t know why, you would probably be angry,” she said.

Jill Montgomery, a fifth-grade teacher and SOT chair at Bozarth Elementary School, said her team helped decide how to use an extra humanities position last school year. An instructional aide was hired instead, with the rest of the funding going toward classroom supplies.

Another decision SOTs will influence (with district input on best practices) is how to spend professional development dollars. “Sometimes (development) has to do with building leadership among the students, sometimes it has to do with the climate and culture of the school, but it will be up to SOTs to help assess: What are the needs?” Wooden said.

Accountability

While school associate superintendents will review operational plans and be responsible for tracking performance and compliance, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Steve Canavero said oversight responsibilities in the reorganized district would rest with him, as well as the Department of Education and State Board of Education. Issues that can be fixed with regulatory changes will go through the state board.

“I will continue to work with the state board if more formal action is required, or more formal actions are initiated by me,” he said.

The reorganization gives Canavero the authority to take action to ensure its mandates are carried out in accordance with the law. Districts also have to cooperate with him in providing certain budget information when requested.

“Given that the State Board of Education and I have been sued on this matter before, I’m not going to delve into specifics about what I will or will not do with this newly granted authority,” he said. “But I can say that I fully intend, as I have since the passage of the initial bill a couple years ago, to see through the reorganization in a manner consistent with law and regulation, and will use the granted authority to the full extent of the law should it be necessary.”

Three ways the district is responding to concerns

1. Roberson acknowledged instances where SOT hiring recommendations were not followed last year. The law says that the superintendent, in consultation with the school associate superintendent, makes hiring decisions, but Roberson was emphatic about the influence of SOTs. Wooden said CCSD was facilitating a districtwide meeting where teams could discuss fixes for systemic or school-specific issues they’ve seen at this point in the rollout.

2. The district is preparing to release a series of videos featuring school leaders who achieved exemplary diversity on their teams last year, reflecting the community around them.

3. Awareness about elections and the public nature of SOT meetings will be emphasized this school year. “They want the community around their school to know that they are invited, even though they are not the elected person on the team,” Wooden said. “Other parents and community members can come and have input. ... (And) I think our schools will make a really concerted effort to ensure that the election process is more widely publicized.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy