Monday, Aug. 21, 2017 | 2 a.m.

The American Society of Civil Engineers is working on an updated report for Nevada, but earlier this year, representatives told legislators that the state is “on the right track,” and noted some improvements since the first report was completed. They applauded the state for improving highway infrastructure with Interstate 11, its renewable energy portfolio and the use of drone technology to regularly monitor infrastructure. Local gas-tax revenue helped improve infrastructure in Clark and Washoe counties, though there is a need for fuel-revenue indexing elsewhere. In 2014, ASCE said aviation needed $56 million in improvements, and this year, it noted that the Nevada Aviation Technical Advisory Committee recommended $19 million.

Infrastructure grades

Grades for the nation are from 2017; from Nevada are from 2014:

• Aviation: Nevada C-, U.S. D

• Wastewater: Nevada B, U.S. D+

• Solid waste: Nevada B-, U.S. C+

• Schools: Nevada D, U.S. D+

• Drinking water: Nevada C-, U.S. D

• Dams: Nevada D+, U.S. D

Nevada also received a C- for transportation and a C- for flood control.

“We have bridges that are falling down,” then-candidate Donald Trump told Fox last August, pledging to double the amount Hillary Clinton wanted to spend on infrastructure as president of the United States. “We’ll get a fund, we’ll make a phenomenal deal with the low interest rates and rebuild our infrastructure.”

One year later and eight months into his presidency, Trump has continued to double down on his lofty promises — during “Infrastructure Week” in June, he told his supporters in Cincinnati that the U.S. “deserves the best infrastructure in the world.” But the administration has been slow to move its $1 trillion plan forward. Different factions of lawmakers in Washington, D.C., are divided over how such a bill should be structured. The Republican-controlled Congress is focused on other initiatives such as tax reform, and Democrats, whose votes would be necessary to pass an infrastructure bill, feel increasingly alienated from a White House that has done little outreach.

In some cases, the administration has sent mixed messages. Trump’s proposed budget included $200 billion for infrastructure but also cut $255 billion from existing programs that fund highway repairs and rural airports. Some recent economic indicators suggest that cities and states, the bodies that build most infrastructure, are waiting to fund new projects until they have more certainty about how many federal dollars could be cut or come their way.

A recent analysis by Reuters found that in the first seven months of the Trump administration, new municipal infrastructure deals were down by about 20 percent from the same period last year. As local governments watch the federal government’s next move, experts say there is a clear need for new roads, bridges, pipes and transmission lines throughout the country. The nation’s infrastructure received a D+ this year on the American Society of Civil Engineers’ annual report card (Nevada received a C- in 2014, and the ASCE does not plan to release a new report card for the state until next year).

“There is still a lot of deteriorating infrastructure around the country,” said Chuck Joseph with ASCE’s Southern Nevada branch, who is working on the state’s new report card. “Nevada is much better positioned than other states because our infrastructure is much younger.” He stressed the importance of building infrastructure that suits the state’s needs as its population grows and technology changes the way consumers think about everything from transportation to energy.

Who pays for infrastructure improvements?

How municipal bonds fund big projects

• What are they? Municipal bonds are securities issued by state and local governments. Cities, counties and states use them to fund capital-intensive projects, such as highways and schools.

• How do they work? Investors loan money in return for low interest payments. It’s seen as a conservative, low-risk investment option that’s often tax-exempt.

• How are they structured? There are two main types of municipal bonds — general-obligation bonds and revenue bonds. The first category is backed by the credit of a municipality, which could theoretically raise taxes to pay off the debt. The other is issued by municipalities too, but it’s backed by project revenue like road tolls.

That’s changing. As our interaction with infrastructure changes in areas like energy and transportation, experts say regulators will need to find new funding mechanisms. Right now, most transportation upgrades are paid for by the fuel-revenue index. But what happens when more electric vehicles hit the roads and fuel-tax revenue decreases? Even though regulators don’t think there will be an issue for several years, municipalities across the country are debating where to go next. Many believe the most equitable solution would be to assess a fee based on road use, or miles driven. Others, including the Trump administration, have encouraged public-private partnerships.

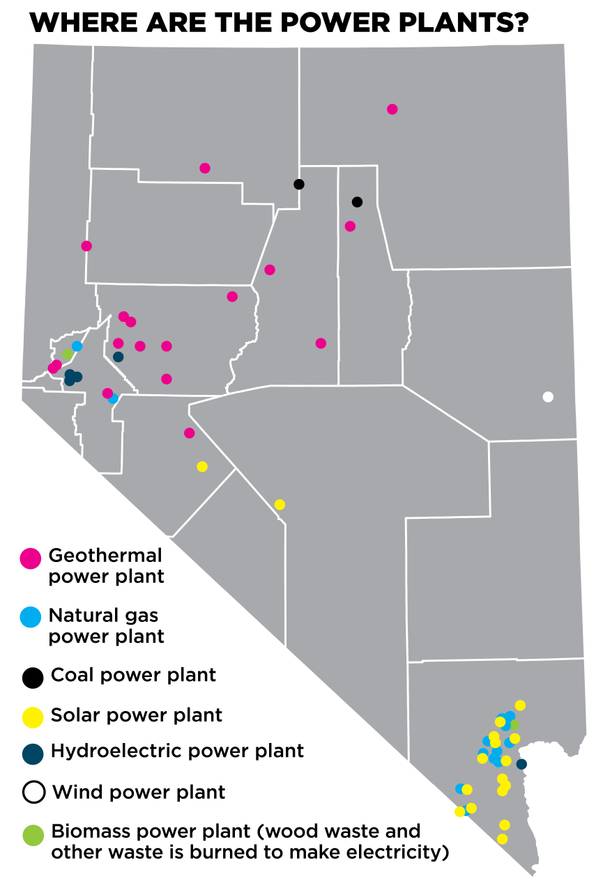

A similar dynamic is playing out in the energy sector as power infrastructure becomes more distributed. Consumers who have solar panels, for instance, are making a private investment to generate electricity and are paid for their excess energy through the net-metering program. In competitive markets like the one that Nevada is considering, private companies are investing in power plants, rather than leaving most of the investment decisions up to one or two utilities. What this means will depend a lot on how a competitive market is structured in Nevada.

Water infrastructure

The Southern Nevada Water Authority has been proactive in building physical infrastructure to protect the region’s water supply in Lake Mead. The man-made reservoir, which has been dropping for years, is under increased pressure from water users and a changing climate expected to bring heat and decrease water elevations through evaporation and changes in snowmelt.

The problem: Most of the Las Vegas Valley’s water — 90 percent — is drawn from Lake Mead. Long aware of this fact, the water authority finished constructing a third intake in 2015 that would allow it to tap the lake even if the reservoir’s elevation were to drop below critical levels. That project, including a third pumping station, cost about $1.5 billion and was funded through low-interest municipal bonds.

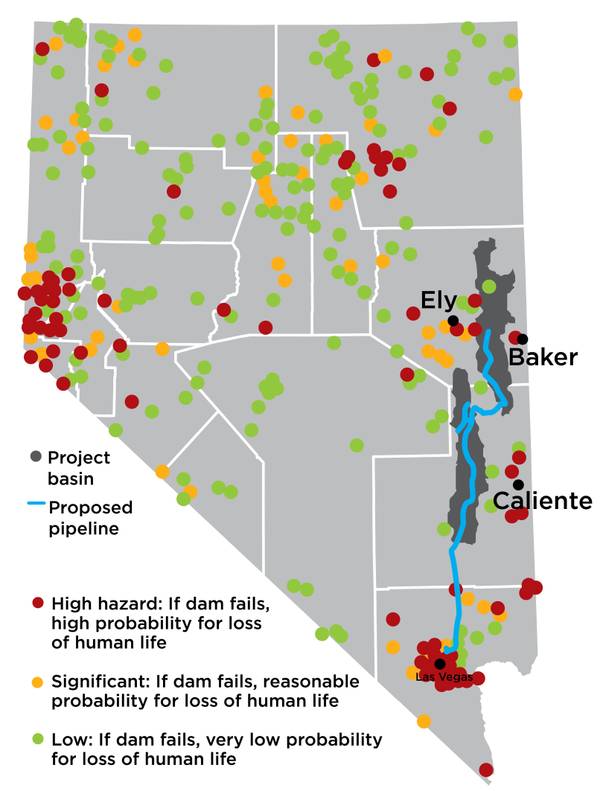

As Lake Mead is expected to drop, the valley’s population is expected to grow. Worried about a water shortage, the water authority in 1989 sought permission to construct a pipeline (see map) to convey billions of gallons of groundwater across the state. Three decades later, the plan is still being pushed by the SNWA but remains mired in legal proceedings. The 250-mile pipeline, which would cost about $3.2 billion, would become one of the state’s largest infrastructure projects. For reference, the Raiders stadium is expected to cost about $2 billion.

Flood channels

The Clark County Regional Flood Control District, started in 1985 and funded with a quarter-cent sales tax, is a master plan to improve infrastructure in the county. According to a spokesperson, the district is about 75 percent complete — at 91 detention basins and 612 miles of flood channels/storm drains — with full execution expected to take another two to three decades. That means adding 34 basins and more than 200 miles of conveyance. To date, the district has spent $1.8 billion on flood control.

Another pipeline?

In states throughout the West, most of the water supply goes toward irrigation. In Montana, it’s nearly 94 percent, and in Nevada almost 60 percent goes to help agriculture and ranching. But as sprawling cities have grown, from Phoenix to Los Angeles to Denver, water has often been transferred from rural areas to cities, where demand is higher. This trend is likely to continue, as Western cities are predicted to keep growing. And some groups believe more infrastructure will be necessary to support the transfer of water.

Last year, New York investment firm Water Asset Management told Nevada legislators that the state needed not only a north-south pipeline but another running from east to west, connecting the Humboldt River to the northern Truckee River. Such infrastructure would allow the state to more equitably allocate its water resources.

A lot of water for a dry state

Nevada has hundreds of dams, including reservoirs in state parks, ponds tied to industrial plants, detention basins for flood control and dams for mining byproducts and agricultural irrigation water. The state classifies about 140 as “high hazard,” meaning high probability for loss of human life if the dam were to fail. Of those, 100 or so are designed for flood control, with the rest split between agricultural, municipal and recreational use.

Eddy Quaglieri, engineering manager for the Nevada Division of Water Resources, says dams in the Las Vegas Valley tend to be high-hazard because of the proximity to dense population, but he adds that the majority of the structures are built to modern design standards and are mostly in good condition.

The division monitors dams throughout the state, typically regulating and inspecting those more than 20 feet high or holding at least 20 acre-feet of water, plus smaller ones with high hazard levels (though the Bureau of Reclamation and Army Corps of Engineers monitor and regulate their own inventories). Inspection frequency depends on a dam’s condition and hazard level.

The proposed SNWA pipeline would stretch 300 miles from Las Vegas to areas near the Great Basin, where the water authority owns 23,000 acres of land and more than 100,000 acre-feet of water rights. Architects of the plan envisioned pumping water south if resources were to grow scarce. But the Great Basin Water Network challenged SNWA’s permits for the water rights, and the issue is still tied up in court.

Transportation

Existing projects

• $47 million for U.S. 95 improvements and Centennial Bowl: The 2,500-foot flyover is designed to improve traffic in Nevada’s third-busiest freeway intersection. Completion: July 2017 (Phase 1)

• $318 million for Interstate 11: Will connect Las Vegas and Phoenix via interstate; Illia said they are the nation’s biggest cities not connected that way. Completion: October 2018

• $1 billion: Project Neon Nevada’s biggest public works project is widening the Spaghetti Bowl. Completion: 2019

How the Nevada Department of Transportation determines project priority

1. The department looks at considerations such as safety and traffic.

2. It considers feedback from outside groups (politicians, businesses, residents).

3. Projects are entered into the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), which is an annual process the department uses to plan out a 10-year list of projects.

4. Public comment is taken on the STIP.

5. The STIP is reviewed by the State Transportation Board.

6. Approved projects put out bids for contracts.

“I’d say we’re very lucky,” says Tina Quigley, general manager of the Regional Transportation Commission of Southern Nevada. “A lot of communities at this point are stuck waiting for the federal government.” When it comes to maintaining and constructing roads, Quigley said Las Vegas is in a good position compared with many other cities across the country because it has funding.

In November, Clark County voters approved index fuel taxes for infrastructure until 2026. This gave the RTC the ability to spend on road improvements; it has already green-lit about 171 design and construction projects valued at $432 million and creating more than 5,500 jobs.

But there is always a need for more transportation infrastructure, and Southern Nevada has a lot of potential projects on the table. “There are lists and lists and lists,” said Tony Illia, a spokesman for the Nevada Department of Transportation. He said a fair amount of work on roads and bridges got shelved during the latest recession but is starting to come back online.

• Light rail: As Southern Nevada grows, Quigley stressed the need for a diverse transportation mix that could include light rail, urban rail and sharing commutes using on-call apps such as Uber.

• High-speed rail: For nearly a decade, planners have talked hopefully about building a high-speed rail connection to Southern California. But developers have run into difficulty securing the necessary funding for the $8 billion project, which would connect Las Vegas to Victorville and eventually Los Angeles. XpressWest, the company behind the project, tried to finance it with a federal loan that was denied in 2013. The project restarted as the company entered into an agreement with a Chinese rail firm, but that agreement also was dissolved. A company official recently said it was seeking potential partners and that federal laws encouraging foreign investment could help.

• Automation and electric vehicles: In the coming years, regulators expect transportation to become increasingly automated and electric. That shift will offer opportunities to increase efficiency, Quigley said, but it is going to require new infrastructure to be built on top of existing roadways. To work autonomously, vehicles need sensors to communicate with bike lanes, traffic lights and other infrastructure. Las Vegas is preparing already.

One local application: Audi recently came out with a car that can communicate with Las Vegas traffic lights. The “vehicle-to-infrastructure” platform will tell you how many seconds you have before a red light expires. Such high-tech infrastructure is being tested in downtown Las Vegas’ Innovation District, where data on self-driving vehicles is being collected in real-time situations. During CES last year, the district received a lot of attention for sending an autonomous electric bus down Fremont Street.

One infrastructure impact: Audi’s new model notifies the driver when a light is about to change. As a result, more cars might move through a green light, decreasing traffic and clearing up the roads.

Energy infrastructure

Energy consumption by sector (2015)

• Transportation 32.4 percent

• Industrial: 25.2 percent

• Residential: 23.3 percent

• Commercial: 19.2 percent

Within the next two decades, planners expect the grid to become nimbler as utilities beef up renewable energy offerings while integrating customer-supplied power from solar panels and storage batteries. Several dynamics are expected to dictate future investment in the grid.

“When you are making changes, you’re turning this giant ship,” said Gretchen Bakke, an assistant professor of anthropology at McGill University in Montreal and the author of a book on the grid.

There is a trend among Western states toward more collaboration. Traditionally, each state has had a discrete power market controlled by one or two monopolistic regulated utilities. That is starting to change. NV Energy participates in a Western market that allows utilities to share energy supplies. Increased coordination helps avoid construction of redundant infrastructure.

Another trend is increased responsiveness. A modernized grid, often called a “smart grid,” is expected to include more sensors and controls to communicate with consumers about their usage in real time. With the possibility of having more home technology connected to the grid — storage batteries, electric vehicles, rooftop solar — utilities see this as an important and practical step forward. In some cases, it’s already here. NV Energy’s installation of smart meters, which help customers manage their power and make decisions about their usage, is one example.

A third trend is demand for renewables. Many transmission companies expect to see more demand for new power lines as utilities and Western states place more emphasis on adding wind and solar farms. New transmission is often needed to connect solar and wind plants in rural areas with consumers in cities. A leaked list of priorities for the Trump administration recognized this demand. The list of 50 projects mentioned two power lines, including one that would stretch from a Wyoming wind farm and cross through Boulder City to deliver power to California.

Technology

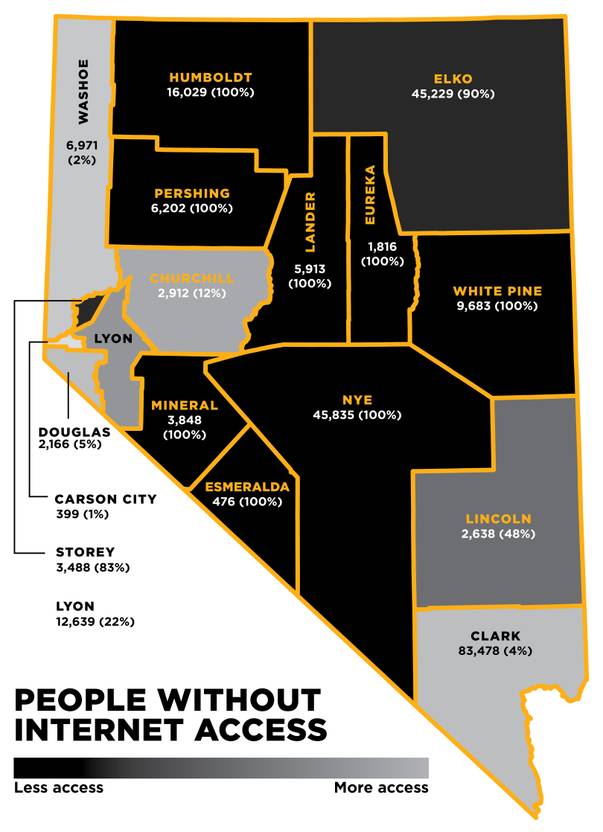

In 2017, access to the internet can be as essential to a region’s economic success as energy. But throughout the country, there is a divide in service quality and options between urban and rural areas. Nevada is no different. The FCC, in its 2016 Broadband Progress Report, found that nearly 40 percent of rural Americans lacked access to the minimum broadband speed of 25 Mbps. That’s compared with only 4 percent of urban Americans. In an economy increasingly globalized, digital and interconnected, that can give cities a competitive advantage and make it difficult for rural small businesses to compete. Only 4 percent of residents in Clark County lack access to fixed (nonmobile) advanced telecommunications. Compare that with sparsely populated areas, such as Esmeralda and Humboldt counties, where the FCC report showed 100 percent of the population without these services.

That’s starting to change. This year, Valley Electric Association, the rural co-op utility serving Pahrump, announced a partnership with data company Switch that would use a fiber-optic line to bring high-speed communications to rural areas from Fallon to Pahrump. State officials in 2014 also published a plan to expand high-speed internet access to rural areas.

Schools

What's coming

• 2017-18 school year: 7 new schools, 2 replacement schools

• 2018-19 school year: 4 new schools

In 2014, the American Society of Civil Engineers identified school infrastructure as Nevada’s weakest point. At the time, it reported that 45 percent of schools within Clark and Washoe counties were more than 30 years old. ASCE found that Clark County’s unfunded infrastructure needs came to a total of more than $6.5 billion. In an update prepared for legislators this year, the ASCE reported that Clark County is beginning to make progress. The 2015 Legislature gave the Clark County School District bonding authority to modernize its infrastructure. That capital improvement program is expected to bring in $4.1 billion over the next decade.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy