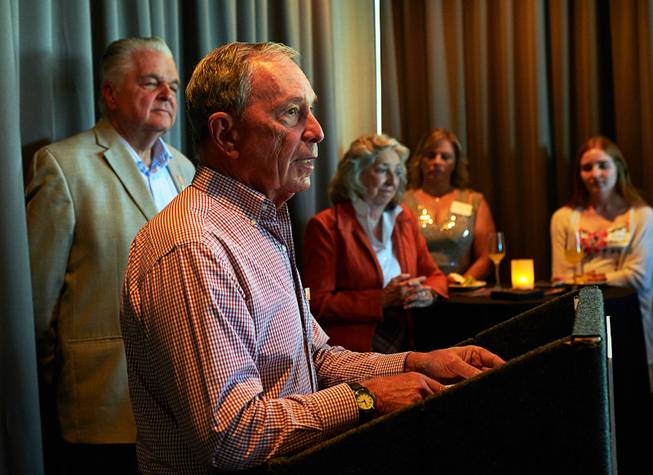

Bridget Bennett / The New York Times

Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire and former mayor of New York, speaks at a fundraising brunch for Steve Sisolak, left, the Democratic nominee for governor of Nevada, in Las Vegas on Sunday, Sept. 16, 2018. Bloomberg is actively considering a campaign for president as a Democrat in 2020.

Tuesday, Sept. 18, 2018 | 2 a.m.

SEATTLE — Michael Bloomberg is actively considering a campaign for president as a Democrat in 2020, concluding that it would be his only path to the White House even as he voices stark disagreements with progressives on defining issues including bank regulation, stop-and-frisk police tactics and the #MeToo movement.

Bloomberg, 76, a billionaire media executive and former New York City mayor, has already aligned himself with Democrats in the midterm elections, approving a plan to spend $80 million to flip control of the House of Representatives. A political group he controls will soon begin spending heavily in three Republican-held districts in Southern California, attacking conservative candidates for their stances on abortion, guns and the environment.

At events across the West Coast and Nevada in recent days, Bloomberg, who was elected mayor as a Republican and an independent, denounced his former party in sharp terms. He urged audiences in Seattle and San Francisco to punish Republicans who oppose gun control or reject climate science. And in Las Vegas on Sunday he called on Democrats to seize command of the political center and win over Americans “who voted Republican in 2016.”

But Bloomberg’s aspirations appear to run well beyond dismantling Republicans’ House majority, and he is taking steps that advisers acknowledge are aimed in part at testing his options for 2020.

After a gun control-themed event in a Seattle community center Friday, Bloomberg, who has repeatedly explored running for president as an independent in the past, said in an interview that he now firmly believes only a major-party nominee can win the White House. If he were to run, Bloomberg said it would be as a Democrat, and he left open the door to changing his party registration in the coming months.

“It’s impossible to conceive that I could run as a Republican — things like choice, so many of the issues, I’m just way away from where the Republican Party is today,” Bloomberg said. “That’s not to say I’m with the Democratic Party on everything, but I don’t see how you could possibly run as a Republican. So if you ran, yeah, you’d have to run as a Democrat.”

Bloomberg said he had no specific timeline for deciding on a presidential run: “I’m working on this Nov. 6 election and after that I’ll take a look at it.”

There is considerable skepticism among Democratic leaders, and even some of Bloomberg’s close allies, that he will actually pursue the presidency, because he has entertained the idea fruitlessly several times before, and shown little appetite for the rough-and-tumble tactics of traditional partisan politics. A campaign would require him to yield his imperial stature as a donor and philanthropist, and enter a tumultuous political and cultural climate that could make him a highly incongruous candidate for the Democratic nomination.

Though he has received a hero’s welcome from Democrats for his role in the midterms, Bloomberg is plainly an uncomfortable match for a progressive coalition passionately animated by concern for economic inequality and the civil rights of women and minorities.

In the interview Friday — his first extended comments on his thinking about a 2020 presidential run — Bloomberg expressed stubbornly contrary views on those fronts. He criticized liberal Democrats’ attitude toward big business, endorsing certain financial regulations but singling out a proposal by Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., to break up Wall Street banks as wrongheaded. He also defended his mayoral administration’s policy of stopping people on the street to search them for guns, a police tactic that predominantly affected black and Latino men, as a necessary expedient against crime.

And while Bloomberg expressed concern about allegations of sexual misconduct that have arisen in the last year, he also voiced doubt about some of them and said only a court could determine their veracity. He gave as an example Charlie Rose, the disgraced television anchor who for years broadcast his eponymous talk show from the offices of Bloomberg’s company.

“The stuff I read about is disgraceful — I don’t know how true all of it is,” Bloomberg said of the #MeToo movement. Raising Rose unprompted, he said: “We never had a complaint, whatsoever, and when I read some of the stuff, I was surprised, I will say. But I never saw anything and we have no record, we’ve checked very carefully.”

Bloomberg said the media industry was guilty of not “standing up” against sexual misconduct sooner, but declined to say whether he believed the allegations against Rose. “Let the court system decide,” he said, while acknowledging that the claims involving Rose might never be adjudicated in a legal proceeding.

Rose, 76, has been accused by numerous women of unwanted and coercive sexual behavior, including claims that he groped female subordinates and exposed himself to them. He was fired by both CBS, where he hosted a morning show, and PBS, which broadcast the program “Charlie Rose,” which Rose recorded in the Bloomberg office. Bloomberg TV also terminated an arrangement that allowed it to rebroadcast Rose’s show.

“You know, is it true?” Bloomberg said of the allegations. “You look at people that say it is, but we have a system where you have — presumption of innocence is the basis of it.”

On policing, Bloomberg said that there had been “outrageous” cases of police abuse and unjustified shootings around the country. But he said stop-and-frisk searches had helped lower New York City’s murder rate and insisted that the policy had not violated anyone’s civil rights.

He dismissed a court ruling to the contrary as the opinion of a single judge that could have been overturned on appeal. Bloomberg suggested many Democrats would agree with him on policing.

“I think people, the voters, want low crime,” Bloomberg said. “They don’t want kids to kill each other.”

Asked whether, in retrospect, he saw any civil rights problems with stop-and-frisk tactics, Bloomberg replied: “The courts found that there were not. That’s the definition.”

In 2013, a federal district judge, Shira A. Scheindlin, ruled that the stop-and-frisk policy had been carried out in an unconstitutional way. Bloomberg’s administration assailed the decision and vowed to appeal it, but his successor, Mayor Bill de Blasio, a Democrat, declined to do so.

Despite his obvious divergence from the Democratic Party on some key issues, advisers to Bloomberg believe he would have a plausible route to its presidential nomination if he stood out as a lonely moderate in a field of conventional liberals challenging President Donald Trump.

Bloomberg has mapped an energetic travel schedule for the midterms that will also take him to battleground states that would be crucial in a presidential race. He will make stops in Michigan, Florida and Pennsylvania and address influential liberal groups, including the League of Conservation Voters and Emily’s List, aides said. And he is weighing a visit to the early primary state of South Carolina.

Bloomberg is also preparing to reissue a revised edition of his autobiography, “Bloomberg by Bloomberg,” aides confirmed.

Democratic leaders have so far embraced Bloomberg, giving him a regal reception aimed at ushering him securely into the party. At a climate conference in San Francisco, he stood beside Gov. Jerry Brown of California, a popular Democrat, to show support for the Paris climate agreement. And in an embrace laden with political symbolism, Rep. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., the House Democratic leader, introduced Bloomberg at two events as a herculean champion of the environment and a master of business and government.

“His name is synonymous with excellence,” Pelosi said, at a dinner atop the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “And he knows how to get the job done.”

In a private conversation at the dinner, Bloomberg pressed Pelosi to govern the House in a bipartisan way if Democrats take power, he said — a message he also trumpeted publicly in Las Vegas as he pleaded with Democrats to pursue the center. “Candidates who listen to voters in the middle are more likely to reach across the aisle and to get things done,” Bloomberg argued there.

Beyond the most rarefied political precincts, however, Bloomberg and his White House hopes have stirred a mixture of curiosity and consternation. In Nevada, Barbara Buckley, a former speaker of the state Assembly, expressed surprise at the notion of a presidential campaign.

“He’s still a Republican, isn’t he?” Buckley said at a fundraising dinner hosted by the Women’s Democratic Club of Clark County. Of Bloomberg running as a Democrat, she said, “I think people would question why he’s changing at this point in his career.”

Tick Segerblom, a progressive lawmaker in Nevada, said he appreciated Bloomberg as an ally of the Democratic Party and would keep an open mind about him as a candidate. Segerblom, who hosted Warren at an event over the summer, volunteered to welcome Bloomberg at his home.

“He’s been so fantastic on the environment and so fantastic on guns,” Segerblom said. “I don’t know, when you get into some of the economic issues, how progressive he is.”

Bloomberg’s advertising for House Democrats is expected to begin in the coming days, with his spending trained on a few clusters of races in expensive television markets, including in California and Pennsylvania. His first three targets are Los Angeles-area seats held by Reps. Steve Knight and Dana Rohrabacher, Republicans running for re-election, and an open seat near San Diego held by Rep. Darrell Issa, a Republican who is retiring.

The advertising blitz includes $4 million in the final 10 days of the election in the Los Angeles media market alone, aides said. But underscoring Bloomberg’s discomfort with important elements of the Democratic Party, it is not expected to include California’s 45th Congressional District, where Katie Porter, a liberal law professor who is a protégée of Warren, is challenging Rep. Mimi Walters, a conservative Republican.

Close allies of Bloomberg are divided as to whether it would be wise for him to run for president in 2020, and at least one longtime associate has predicted that he will never seek the White House. Bradley Tusk, Bloomberg’s former campaign manager who helped him explore an independent candidacy in 2016, declared at a recent dinner in Washington, D.C., that he expected Bloomberg to toy with running before opting out yet again, multiple people who attended the event confirmed.

Asked about that prediction, Tusk said in a text message, “No one is better suited to be president than Mike Bloomberg.”

“Running for president and being president aren’t always the same thing,” Tusk continued. “So we’ll see what he decides, but he’s the best option by far.”