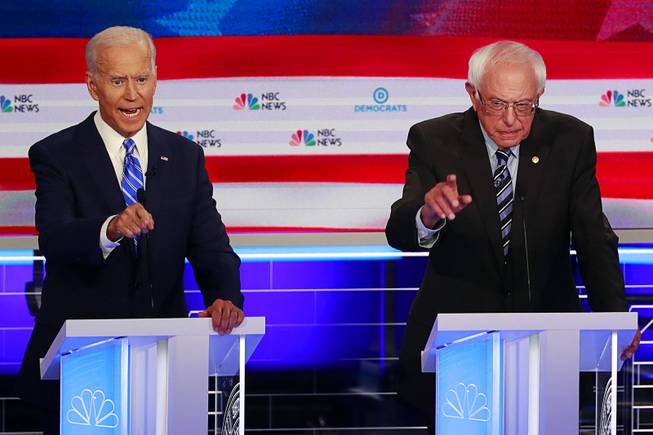

Wilfredo Lee / AP

Democratic presidential candidate former vice president Joe Biden, left, and Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt speak at the same time during the Democratic primary debate hosted by NBC News at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, Thursday, June 27, 2019, in Miami.

Sunday, June 30, 2019 | 2 a.m.

WASHINGTON — The Democratic Party is in no mood for a coronation.

Joe Biden stepped onto the debate stage Thursday night as a front-runner by default more than depth of support, and walked away with a more fragile standing atop the sprawling Democratic field. His rivals showed little deference to the former vice president and longtime senator — a Democratic elder statesman who has cast himself as the rightful heir to the legacy of Barack Obama, the president he spent eight years serving alongside.

The questions surrounding Biden's viability are a proxy for the broader debate among Democrats about the best path to defeat President Donald Trump, and about the future of a party that has been trying to reconcile for a generation the role that government should play in American life.

Can a moderate like Biden attract some of the white, working class voters who abandoned Democrats for Trump in 2016 or should the party embrace the energy of its left flank and tap a progressive, like Sens. Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders, who are pressing for sweeping government intervention in the economy? Are Biden's decades of experience in Washington an antidote to Trump, who took office having never served in government, or would a fresher face, such as California Sen. Kamala Harris, help Democrats ramp up general election turnout among young voters and minorities?

Last week's back-to-back debates did little to answer which course Democratic voters will take when primary contests begin early next year. But the face-offs did thrust the divisions within the party into the spotlight, as candidates swapped many of the niceties that have governed the primary's early months for pointed and sometimes personal attacks.

It's no surprise that Biden, who has led early polling since jumping into the race in April, found himself a frequent target. Yet the breadth of the critiques — taking aim at his age, his style of governing, his policy positions and his views on race — were at times breathtaking. Biden alternated between forceful defenses of his record and stumbling answers that suggested he wasn't fully prepared for the intensity of the attacks.

The debate's enduring exchange came when Harris challenged Biden over his past opposition to school busing and recent statements about working with segregationists. Harris, a former prosecutor who would be the first black woman elected president, wove her own personal history into her blistering critique of Biden's words and actions.

"Vice President Biden, I do not believe you are a racist, and I agree with you, when you commit yourself to the importance of finding common ground," Harris said. "But I also believe — and it's personal — it was actually hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on the segregation of race in this country."

Candidates also challenged Biden's record as a dealmaker during his tenure as vice president, jabbing at both a source of pride for Biden and one of his stated qualifications for the presidency. Rep. Eric Swalwell, one of the youngest candidates in the race, repeatedly called on the 76-year-old to "pass the torch" to a new generation.

"I'm still hanging onto that torch," Biden shot back.

To some Democrats, Biden still remains a safe choice to take on Trump, a president the party views as an existential threat to American democracy. With his centrist policy positions and everyman stylings, Biden is seen as a candidate who can win back some of the working class voters who were drawn to Trump and helped tip Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin in the Republican's favor in 2016. He also has deep ties with black voters, a crucial Democratic constituency, particularly after spending eight years as Obama's No. 2.

Other Democrats argue the country and the party have changed dramatically, even in the two-and-a-half years since Obama and Biden left the White House. Liberal Democrats, including Warren and Sanders, are unabashedly embracing costly, big government programs to address economic inequality, climate change and health care costs. Sanders went so far as to concede that his "Medicare For All" program would increase taxes on middle class Americans, though he argued their health care costs would be lower.

A historic number of women and minorities are agitating to take control of an increasingly diverse party. Some candidates, including 37-year-old South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, are openly calling for Democrats to embrace a new generation of leaders.

Democrats have tested versions of these political propositions in recent decades. Facing unpopular incumbent President George W. Bush in 2004, Democrats went with a seasoned centrist, Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, who would lose the general election. In 2016, the party establishment, and ultimately voters, rallied around Hillary Clinton — a secretary of state, senator and first lady of unmatched experience, who was nevertheless defeated by Trump.

In contrast, Obama surged to the presidency at age 47 and with less than two years in the Senate on his resume, buoyed by historic turnout among younger voters and African Americans. Another young Democrat, Bill Clinton, rode a call for generational change to the top of the 1992 primary field and two terms in the White House.

In the Trump era, where so many norms have been upended, political history may be an imperfect guide as Democrats weigh their options in the 2020 race. This week's debates may not have offered any answers, but the party's choices were never clearer.