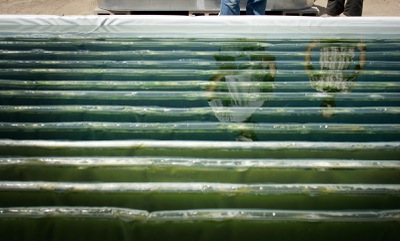

Colorado State’s Engine and Energy Conversion Lab in Fort Collins is in an old power plant the city leases to the university. Lab Associate Director Morgan DeFoort, above, opens the door of an algae growing area of Solix Biofuels, a company housed in the lab. Algae are 80 percent oil by mass and can be used for fuel after processing.

Sunday, Aug. 24, 2008 | 2 a.m.

New Industries Thrive

On the road to the Democratic National Convention, the Sun looks in to two growth industries in the Intermountain West. New Mexico has recently become a major hot spot for film and television productions, while Colorado is taking advantage of environmentally friendly technology to push its economy forward. (2:51)

Colorado State's Engine and Energy Conversion Lab in Fort Collins is in an old power plant the city leases to the university. Lab Associate Director Morgan DeFoort, above, opens the door of an algae growing area of Solix Biofuels, a company housed in the lab. Algae are 80 percent oil by mass and can be used for fuel after processing.

Reader poll

Sun Expanded Coverage

W. S. Sampath was at a loss. The Indian-born professor of engineering at Colorado State University had just been told that he had a great idea for manufacturing solar panels more cheaply but he needed a business plan to turn it into something that would sell.

“I didn’t know what a business plan was,” Sampath said, sitting in an office where the decor — shabby, absent-minded professor without the charm — lent his statement ample support. Sampath conceded that he needed the help; he sometimes speaks in totally inscrutable scientific jargon.

Luckily for Sampath, someone else at the university knew business plans.

Hunt Lambert, now vice president for economic development at Colorado State, had been a venture capitalist and a start-up company junkie who’d also held big posts at U.S. West, the telecommunications company. Lambert lent his expertise to Sampath and even found the fledgling company a chief executive. They in turn introduced Sampath to investors.

A year ago the company had four employees. Now it has 79, and next year the payroll will swell to 500 when a manufacturing plant opens in Longmont, not far from here.

But without Lambert and CSU’s determined efforts to get research to the marketplace, Sampath’s idea would have earned praise from colleagues and sat in a desk drawer.

None of this is coincidental. Policymakers in Colorado and a few other Intermountain West states are trying to create a new economic future, one more reliant on brain power than natural resources or migration of people West, and, thus, more sustainable.

The Intermountain West was first a way station to the West Coast, a region dominated by railroad development and a federal government intent on taming and settling the region. Since World War II, the region has grown rapidly, its economies reliant on extracting natural resources — timber, oil and gas, metals and minerals — as well as the continued American migration westward.

Now, though, its newly urban populations expect better government and more from it. Even as new residents grow wary of the industries that extract dwindling natural resources, economies based solely on the arrival of new people are no longer viable or desirable. Policymakers across the region — though less so in Nevada — are using every tool they have to create a new economic future.

Politically, this could lead to sweeping change throughout the region. The party or politicians best able to leverage the West’s resources to create sustainable prosperity will have a head start on the region’s future.

In the postwar era, and especially as libertarians took control under Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, Republicans dominated the mountainous landscape. Their policies of low taxes and a laissez-faire approach to unfettered development and logging and mining allowed the West to grow quickly and create vast new wealth. Voters rewarded them.

The Democratic Party’s strongholds were in Eastern industrial cities, which had little in common with the West. The party’s foot soldiers were labor union members and civil rights activists. Without very many black residents or manufacturing facilities, labor and civil rights didn’t matter as much to the West, and Democrats offered little in the way of a relevant policy profile for the region. When they did offer something relevant, like gun control, they were on the wrong side of the issue.

Now, though, the challenges facing the West will test each political party’s ability to deal with these newer concerns: global warming, air quality, depleted water supplies, traffic, economies in need of new and diversified industries.

The party with an ambitious — and efficient — approach to solving problems will control the political agenda, not just in this November’s election, but in many more to come.

For now, it’s the Republicans who will need to adapt the most.

As former Arizona Republican Congressman Jim Kolbe told the Sun, “The Rocky Mountain states are undergoing a tremendous transformation the Republican Party has not recognized. If it’s going to maintain its dominance, it’s going to have to change to changing circumstances.”

The party has long adhered to the so-called Chicago School model of economics, derived from the University of Chicago’s many Nobel winners who posit that government is a hindrance, not a driver of economic growth.

It’s not a view shared by most economists.

“Clearly public investment is very important and Colorado is making a huge effort to make sure its future is tomorrow’s industries and not yesterday’s,” said Charles de Bartolome, a University of Colorado economist.

Bartolome echoes a recent Brookings Institution report about the Intermountain West written by Mark Muro and Robert Lang, who note that government funded research can drive innovation, which can in turn drive productivity growth, and, finally, higher wages. (One famous example: The Internet came from Pentagon research.)

Colorado State President Larry Penley sees economic development as a key function of public universities.

“You’ve got to get good ideas to the marketplace so they can do things for society,” he said.

In Penley’s five years, the university, long a second player to the University of Colorado in Boulder, has increased its research and development budget 35 percent to $300 million.

Penley has identified the university’s strengths, which include infectious disease and biomedicine and clean and sustainable energy, and given these areas resources while pushing faculty to work together, hustle for grant money and seek out ways to commercialize their research discoveries.

The university helps professors such as Sampath patent their work and then sells licensing rights to companies such as the one he founded, AVA Solar. A university-affiliated foundation owns a small equity stake.

The city of Fort Collins has also gotten into the act. The Engines and Energy Conversion Laboratory, established 16 years ago, is in an old power plant the city leases to the university lab for $1 a year. Researchers and students there are working on practical solutions to the pollution that is the scourge of the developing world.

For instance, unknown to most Americans, only half the world cooks with natural gas or electricity. The other half use stoves that burn wood, coal, dung and other detritus. The resulting indoor air pollution is one of the leading killers in the developing world, with one person dying every 20 seconds from it. So researchers at the lab are trying to create affordable stoves that would reduce those emissions in places such as India and China.

They have also created a $300 fuel-injection retrofit for the two-stroke engine, which is what powers millions of small taxis and sidecar motorcycles in poor countries. Its use will reduce carbon monoxide 80 percent and increase fuel efficiency by 35 percent.

As the lab’s associate director, Morgan DeFoort, pointed out, this isn’t trivial tree-hugging — these pollutants kill millions of people in the developing world.

The company Envirofit, which grew out of the lab, licensed the patents from the university and is commercializing these inventions.

Then there’s Solix, another company with a close relationship with the university. Doug Henston, the chief executive, is a Yale microbiology major who flew A-6 fighter jets off the decks of aircraft carriers before Harvard and Goldman Sachs.

Henston’s company will hook up to coal plants and use the emitted carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, to grow algae. The algae, which use far less water while being more energy-rich than other biomass crops, such as soy, is 80 percent oil by mass and can be used for fuel after processing. (A lot of the world’s petroleum was algae 1 million years ago.)

Henston said renewable energy companies are leveraging the regional taxpayer-funded resources, including the state universities, the Colorado School of Mines and The National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden.

Gov. Bill Ritter, meanwhile, is pushing hard on renewables, following the state’s voters, who passed a law in 2004 requiring 10 percent of electricity to come from renewables.

All this, combined with a strong culture of entrepreneurism in Colorado, has led to a renewable energy boom here.

Similar developments are happening in other Intermountain West states. In Arizona, the focus is on biosciences, with key investments in the state universities and a nonprofit genetic research company.

New Mexico is also relying on technology, but on its creative assets even more.

Albuquerque is now called Tamale-wood, as 2,000 New Mexico residents work in the film and television industry, almost all of them in high-paying union jobs.

Gov. Bill Richardson instituted an aggressive tax incentive program to bring Hollywood east.

Unlike many pie-in-the-sky tax incentive programs that wind up being expensive giveaways to big business with little payoff, this one made sense. In part, it made sense because New Mexico was one of the first. More important, Hollywood loves New Mexico for its weather, diverse locations for shooting, food, laid-back lifestyle, Santa Fe vacation spots and creative assets, according to Lisa Strout, director of the state film office, who was in the industry 20 years.

Film companies can get a 25 percent rebate on gross receipts, corporate income and other taxes and apply for up to $15 million in no-nterest loans. They’ve also created a vocational-tech program at the state’s community colleges, for “below-the-line” work — the carpentry, makeup, costuming and other nuts and bolts of the industry. Now the state is beginning to cultivate homegrown actors, directors and writers.

Strout said policymakers take a cold cost-benefit approach to the industry: “We’ve always treated it as a business.”

TV and movie sets are all over Albuquerque and the hinterlands. The Coen brothers shot “No Country for Old Men” in Las Vegas, N.M. The newest offering of “The Terminator” franchise is being shot in Albuquerque now. With the help of government policy, an important critical mass has been achieved, and now soundstages and other important infrastructure are being built, which will further ratchet up the New Mexico advantage.

On the set of a TV show out this fall called “Easy Money,” producer Brandon Hill lauded New Mexico: “I love it. It’s terrific the industry found this,” he said.

They were shooting the show at a dilapidated strip mall. It’s a comedic drama about a family in the payday loan business written by some “Sopranos” alums. The production pays good money for the space for the day, and the lot is brimming with people carrying equipment, down to a parasol held over the female lead, Laurie Metcalf.

Such is the measuring stick for Nevada, a state that is falling behind its western neighbors in the effort to create a new economy.

Although the state’s long support for gaming and mining can actually be viewed as an aggressive and highly successful form of economic development, the recent Nevada recession has offered evidence the state’s economy is too dependent on gaming and migration of people to service the industry.

In other areas, Nevada hasn’t been aggressive or strategic enough, said Assembly Speaker Barbara Buckley, a Las Vegas Democrat.

One obvious shortcoming: State government, wholly reliant on growth and gaming, is broke.

The university system is cutting nearly 8 percent from its state-funded budget this fiscal year. UNLV has reduced its spending by more than $18 million, laying off dozens of employees and cutting by about 20 percent the amount of money it spends on part-time instructors who teach many introductory-level courses. As a result, full-time professors will have to teach more, leaving fewer hours to apply for research grants.

Michael Skaggs, executive director of the Nevada Commission on Economic Development, is pursuing the growth of alternative energies.

The state has in place incentives to give partial sales tax exemptions on the purchase of equipment needed to build alternative energy plants. And with the help of state congressional leaders, the governor’s office is working with the Bureau of Land Management to secure rights to BLM land for renewable energy development. (Buckley and Assembly Democrats have proposed something similar.)

Skaggs said nine massive energy-producing solar arrays and two geothermal plants, currently in various stages of planning, could make use of that land. He added that a crucial element in this new sustainable business is working with the state’s university researchers.

Skaggs said a “nice triumvirate” of cooperation exists between researchers at the Nevada System of Higher Education's Desert Research Institute, UNLV and UNR. Then, to turn university research into working plants and jobs, Skaggs said, his office is tied into the venture capital community, which can buy the research and put the management team and financing together.

Robert Sweitzer is director of UNLV’s Office of Technology Transfer, which tries to move technology to the marketplace. Sweitzer’s office is working on hydrogen fuel technology, solar energy and a “clean coal” process. Sweitzer said Friday that he had just signed a confidentiality agreement with a Detroit company to commercialize security software.

“We’ve had a lot of success since we revitalized the office,” he said.

One thing the office has not gotten was any word, any sign of help, from the governor’s office, he said. He said he has never heard from Skaggs.

“I mean, for a state official to say they’ve been helping here is just a joke.”

Sun reporter Charlotte Hsu contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy