Aaron McArthur, a UNLV doctoral student writing a history of St. Thomas for the National Park Service, explores the site of the Gentry Hotel. The significance of the the town has changed over the years, he said. “The lessons that people seem to be drawing from it have less to do with matters of faith and ‘grow where you’re planted,’ and more with a cautionary kind of thing about what happens when we’re not responsible stewards of water.”

Wednesday, March 12, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Dry Town, Dry Future

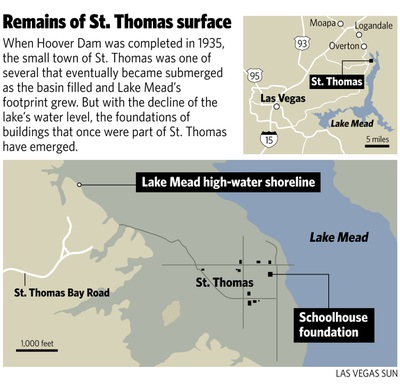

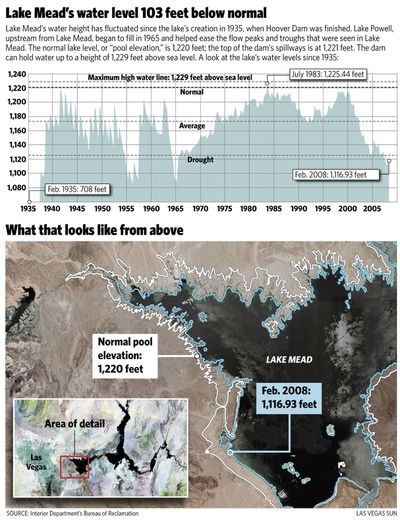

For 60 years, the town of St. Thomas lay beneath the waters of Lake Mead. In 2002, St. Thomas re-emerged from the shrinking lake and scientists don't expect the site to ever be under water again. St. Thomas's appearance offers further evidence of the Southwest's critical water problem. Lake Mead is one of the largest reservoirs in the world and one of the most important water sources in the western United States, however, over the past few years scarce rain and snow amounts have lowered the lake's water levels significantly. According to researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, there is a 50 percent chance Lake Mead will be dry by 2021 if climate changes continue as expected and future water usage is not curtailed.

Sun Archives

- Scientists: Lake Mead May Be Dry by 2012 (2-15-2008)

- Chasing Lake Mead’s Water: Part 1 of 3 (12-29-2006)

- Chasing Lake Mead’s Water: Part 2 of 3 (12-30-2006)

- Chasing Lake Mead’s Water: Part 3 of 3 (12-31-2006)

Water gave birth to the town, and then buried it.

Now years of drought combined with the thirst of a burgeoning Las Vegas Valley have forced Lake Mead to give up all of St. Thomas’ silted remains.

A historian documenting the old Mormon settlement for the National Park Service visited its ruins for the first time Feb. 27 amid a growing belief that St. Thomas may never be covered by water again.

A recent study by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego found that Lake Mead, which supplies 90 percent of Las Vegas’ drinking water and water for all other uses throughout the Southwest, could go dry in 13 years. The region’s water officials have, in large part, dismissed the study as overly pessimistic. But they admit that no one knows how long the drought will last or what role climate change will play in the drying of the Southwest.

Whatever the future may hold for St. Thomas, one thing is clear: The ghost town’s past is a cautionary tale.

Just a few years ago the town was 70 feet under Las Vegas’ supply of fresh drinking water. Although it has peeked above the water before, when the lake was low, never have the ruins of St. Thomas’ concrete foundations, once a popular spot for scuba divers, been so far from the shoreline of the lake that covered them for 65 years.

“What I find interesting about it,” says Aaron McArthur, a UNLV doctoral student who is writing the history of St. Thomas for the National Park Service, “is that in 1945, in 1963, the times it emerged from the water before, there were always reunions here. Reunions in the real sense that, ‘We might have been pushed out, but this is our home.’ ”

“Now most of the people are dead ... Now the lessons that people seem to be drawing from it have less to do with matters of faith and ‘grow where you’re planted,’ and more with a cautionary kind of thing about what happens when we’re not responsible stewards of water.”

McArthur, a Mormon originally from Montana, said St. Thomas teaches that lesson, but also others about family and faith.

As McArthur took his first walk through the town’s remnants last week, he said, “Sometimes I think I understand some of it, but then I didn’t live here when there was no running water and no air conditioning.”

Later that night McArthur would shower in his temperature-controlled condo near UNLV, in the middle of one of the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas.

• • •

The Mormons sent to the scorching valley had settled in 1865 at the confluence of the Virgin and Muddy rivers. They referred to them as rivers, but they might have more rightly been called streams or even creeks. After the Mormons had traveled for weeks in wagons across an unforgiving desert, perhaps those trickles of water, constant through both winter and summer, looked like rivers to them.

Walking through the now bone-dry ruins of St. Thomas, it is possible to imagine girls in gingham dresses kicking up dust while running past the Gentry Hotel. Its curved facade and second-story balcony made it one of the town’s most recognizable buildings.

Clear away the water-sucking, invasive tamarisk plants that choke what was once a dirt highway and picture the rows of cottonwood trees the settlers planted for shade along that highway through town. You can still see the path the road took across the hard-packed earth.

Listen hard and you can nearly hear the school bell ringing or the town’s first radio playing on the steps of the car repair shop while bachelors jawed over the day’s news. Hugh Lord, who owned the garage, refused to leave until the waters were lapping at his doorstep.

Walking from cistern to cistern along dirt trails that lead through the ruins of modern-day St. Thomas, it is evident that here water was central to life.

But water is central to life throughout the Southwest, and it was a dam to control the fickle Colorado River and distribute its waters that eventually put St. Thomas at the bottom of a lake. Construction began on Hoover Dam, then called Boulder Dam, in 1931. Giant hydroelectric power generators would pay for the $48 million project, which would regulate the water delivered to Arizona, Nevada, California and Mexico and create a reservoir known as Lake Mead.

Surveys showed that St. Thomas, along with warehouses at Callville and a cluster of farms at Kaolin, would soon be underwater.

There’s nostalgia about St. Thomas in Overton and Logandale, nearby towns where many descendants of the lost town live. Census records show the settlement never topped more than a few hundred people, even before news came that it would be swallowed by the lake.

Logandale resident Verna Heller, 89, was born in St. Thomas. She remembers how hot it was and how she and the other children would roast ears of corn and steal chickens for fun.

Her family left in 1932, six years before the waters covered St. Thomas. She was 14.

The government moved the town’s cemetery — which held the remains of Heller’s twin brother — to Logandale before the waters came.

Heller recalls nightmares of a scene that would be a dream come true for 21st-century Las Vegas: the lake filling all at once.

“It did come up fast when it came up,” she said. “I was too young to have anything but resentment.”

• • •

When the residents of St. Thomas packed their belongings and moved their homes, brick by brick, out of the path of the growing lake, they weren’t the first to take leave of the valley.

Thousands of years before, the Anasazi, an ancient Pueblo people, knew all too well that life in this area was impossible without plenty of water.

Eva Jensen, an archaeologist with the Lost City Museum in Overton, thinks about them every time she turns on her faucet.

“Everybody should think about that,” she says. “Just what is the capacity of the land and the resources that we have?”

Unable to grow crops to feed a population that had grown too fast to support their nearly 1,000 people, the Anasazi abandoned the dry valley about 1150, after living here for 1,000 years.

“The question we should be asking is: How were they able to survive here for as long as they did?” Jensen says. “Our current community hasn’t been here that long, so we haven’t really been tested. We’ll see how we handle this latest drought.”

Jensen, like many Southwest archaeologists and anthropologists, says there are lessons — or at the very least questions — to be taken from the history of Indians who were eventually beaten down by the realities and natural water cycles of desert life.

“Rapid growth anywhere is a stress on a population. We ... have always used our technology to take care of our problems, but there probably reaches a point where technology can’t fix everything,” she says. “We have to think about changing our philosophy of what we should be doing with the land and how rapidly we can grow.

“That question has been faced by populations throughout the world, throughout time.”

Conservationists and archaeologists alike predict that our relatively young Las Vegas civilization could eventually face many of the same hardships the Anasazi did if urban sprawl and reckless water use continue.

“We have to consider the lessons of the past, and think about what it takes to be a sustainable community,” said Launce Rake, spokesman for the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada, a group that advocates water conservation. “It remains to be seen if we can overcome our self-destructive impulses when it comes to living in the Southwest.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy