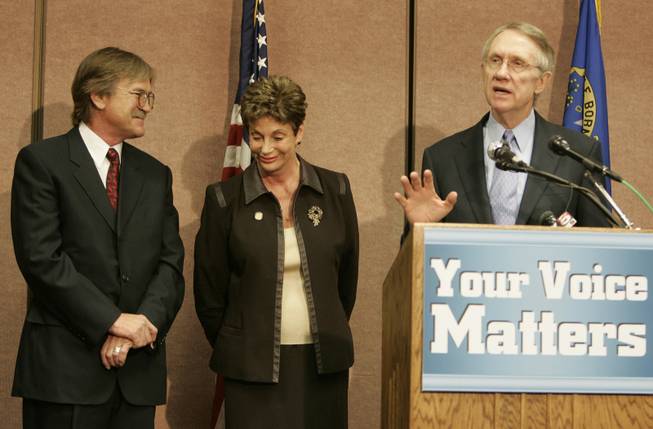

LAS VEGAS SUN FILE

Bob Loux, left, and Rep. Shelley Berkley listen as Nevada Sen. Harry Reid speaks at a news conference on Yucca Mountain in 2006. Reid says Loux’s entire career should be weighed as his fate is decided.

Sunday, Sept. 14, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Reader poll

Sun Topics

The man perhaps most responsible over the past 30 years for thwarting the federal government’s plan for a nuclear waste dump at Yucca Mountain slides into the driver’s seat with a mischievous grin.

He has offered to drive to lunch on this hot August day. His state-issued rusted road hog looks like it belongs on an abandoned lot. The state’s fleet managers must shudder every time they see its grimy government plates.

But out here in this lonely office park where he works, miles from the Capitol in Carson City, the executive director of the Nuclear Projects Agency drives what he wants, and this car fits like a comfortable shoe.

Bob Loux is as independent as the desert sun is strong. With his longish feathered hair parted down the middle, his jeans and his short-sleeved Western shirt with pearl buttons, Loux looks, from behind the wheel of the Chevrolet Caprice, like a character in a ’70s action film.

When Loux goes to Washington, D.C., as he has regularly for three decades, there is no hiding that he is a cowboy — a suit and tie can’t change that. Nevada’s elected officials have privately relished that side of Loux — part cowboy, part rebel. They see it as fitting for a man who for most of his adult life has fought the proposed nuclear dump at Yucca Mountain, about 90 miles north of Las Vegas. Little wonder that he has worked for six governors, and survived, even flourished, under each.

But now Republican Gov. Jim Gibbons — and others — say Loux must go. Loux admitted last week he had unilaterally and improperly boosted his own salary and those of his small staff of state workers, raising his pay from $114,000 to $151,000. It is more than the governor makes, and it violates state law.

An initial review found Loux has been increasing staff salaries since 2006. A more formal audit is under way.

Lawmakers were shocked at the brazen disregard for protocol, especially as the state is suffering an extreme budget crisis. Assembly Minority Leader Heidi Gansert filed an ethics complaint and asked the attorney general’s office to consider a criminal investigation. Democratic Assemblyman Morse Arberry suggested a violation of this magnitude could mean jail time.

Yet in a matter of hours last week, the pay raise scandal morphed into something bigger. It became a debate over Yucca Mountain.

Even though polls show a consistent majority of Nevadans oppose turning the desert into a waste dump, not everyone thinks it is such a bad idea. A tenacious minority has quietly maintained it could bring economic benefits. These few Yucca-friendly voices have kept a low profile over the years and waited patiently for a day like this — an opening to change the debate.

Loux has handed it to them.

Leading conservative pundit Chuck Muth filed a civil suit to force Loux from office, while suggesting federal investigation of funds may be warranted. The head of the state Republican Party inserted party politics into the debate by being among the first to call for Loux’s resignation. Two state Republicans lawmakers from Las Vegas, Sens. Barbara Cegavske and Bob Beers, are introducing a bill to wipe out Loux’s state office and its governing commission. Cegavske still opposes the dump, but wants to create a new division responsible to the governor.

But Democratic Sen. Harry Reid, the U.S. Senate majority leader and a vociferous foe of Yucca, is among those who say Loux’s entire career should be considered as his fate is decided.

Former Gov. Richard Bryan has come to Loux’s defense.

Loux has refused to step down and is awaiting a Sept. 23 hearing before the seven-member commission that oversees his work. He cannot be fired by the governor, only the commission.

None of this was in the air that August noon with Loux and his Chevy. He enjoys wrestling with the federal government, he would say that day at different times and in various ways. Nevada is like the little guy standing up to City Hall, in his view.

It’s fun, he said.

He fires up the old engine, steps on the gas with a foot inside a loafer without socks. Windows down, his hair flies in the wind.

• • •

In 1976, the state’s governor, Mike O’Callaghan brought Loux to the fight, tapping the draft dodging, one-time school teacher to run the state office that would become the federal government’s biggest obstacle to Yucca. Nevada was just beginning to understand its position as a desert outpost for the federal government’s plan to store the waste generated from the nation’s newly operating nuclear power plants.

With Nevada’s history of atomic weapons testing, its vast tracts of federally owned land and its thinly populated rural areas tending to embrace the Cold War nuclear program, not everyone was against the dump.

Loux was. A young man in the 1960s who avoided being drafted for the Vietnam War by faking hearing loss, he was more interested in a renewable energy revolution than a nuclear one. He had been building solar panels on senior housing shortly before he was appointed to the state office.

With federal grant money for the state to study becoming a waste repository, Loux’s office became the clearinghouse for information. By the time Congress in 1982 passed legislation naming the Nevada desert as a potential site, the campaign to stop the dump was being born.

Attitudes toward nuclear power were shifting at the time, after the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 and later after the Cherno-

byl disaster in 1986. Nevadans’ distrust of the federal government grew as test site workers became sick.

In 1983, the Legislature created the Nuclear Projects Agency with a mission to protect the state vis-a-vis federal plans for a waste dump in the desert. Bryan, then the governor, appointed Loux as its first executive director.

A fiefdom was being born.

Over the years, tens of millions of federal and state dollars have flowed to Loux’s office. As other states were dropped from Washington’s list of possible dump sites in 1987, Loux scooped up their best opponents and added them to his team.

Early on, Loux devised a strategy that allowed no dissent from the state’s opposition to the waste dump.

Because Nevada was a small state, without the political clout in Washington it enjoys today, Loux thought any hint at compromise with the federal government would weaken its hand and divide (and conquer) the opposition.

Elected officials learned to fall in line. If anyone in civic life thought there might be an economic benefit to housing the waste site, he kept it mostly on the fringe or to himself. Various pro-Yucca campaigns tried and failed to turn the debate.

Loux’s strategy served the state well.

It brought him a great deal of power. He operated with unique oversight. Though appointed by the governor, he can be removed only by the commission, which meets a few times a year to oversee his work. Rarely, if ever, did the commission review Loux’s budgets. It is more of a policy-setting panel, said Bryan, now the commission chairman. Loux has held the job under six governors. He has never had a performance review.

“They give us free reign to do whatever,” Loux said that day in August. “Which suits me just fine.”

• • •

Every Wednesday, Loux orchestrates a conference call in which scientific, legal and public relations strategies for Yucca Mountain are set.

In recent years, Loux has come to appreciate the flexibility of outsourcing. He pared back his office staff to a handful of longtime employees — a few project officers, an accountant, an IT guy (who is a former slot mechanic). He thinks he can adjust more nimbly to issues that arise by adding or subtracting contractors outside of the sometimes cumbersome state personnel system.

Loux and his team oversee about 50 consultants and lawyers fighting Yucca Mountain from around the world. Labs in the United Kingdom, for example, are studying water corrosion issues.

Those who participate in the Wednesday calls say Loux’s ability to distill the many layers of technical information and make swift decisions make him a formidable leader.

“Bob is the hub,” said Charlie Fitzpatrick, a Texas-based attorney whose firm was hired several years ago and was just awarded another one-year contract for $6 million.

The pay raise scandal came to light only after the fiscal 2008 books were closed and Loux’s budget ran over. Loux explained last week that after an employee retired, he divided the salary among himself and his staff, who were picking up the extra workload. Apparently, he didn’t account for the higher cost of retirement benefits that accompanied the salary increases. That cost helped push him over budget.

He apologized and took full responsibility.

Loux’s detractors say this transgression will be too much even for the commission that oversees him. Critics long have complained the commission is a rubber stamp for the state’s anti-Yucca agenda. When Gibbons tried to appoint a pro-nuclear Nye County commissioner to a vacancy this year, public outcry forced him to retreat.

Muth, the conservative activist, imagines the perfect storm in coming months: Loux is forced to resign; the Legislature convenes next year and eliminates the agency; and a more balanced conversation about Yucca Mountain begins.

“The ball has started rolling downhill,” Muth said.

Losing Loux could be a critical blow to the state’s efforts to block Yucca Mountain, some opponents of the project say.

After all these years, the project is at a critical juncture after the Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced last week it would begin the technical review the nearly 9,000-page project application — a final hurdle. Loux’s expertise would be vital.

Bryan has stood by Loux and scoffs at the idea the state could continue fighting Yucca Mountain without the state office. At least one other commissioner, Joan Lambert, said she wants to review the case before making any decision.

Bryan sees the sharks circling and is quick to warn of the larger stakes.

“The greater danger is to use this as an ability to eliminate the state’s opposition,” he said. “Clearly, the pro-nuke crowd has been out to get Bob for years, now they’ve been handed an issue.”

• • •

Loux has seen his job threatened before. In 1998, the then-chairman of the powerful House Commerce Committee, Republican Rep. Joe Barton of Texas, tried to stop the flow of federal dollars to Loux’s office after auditors found Loux had misused educational funds on anti-Yucca efforts.

Two years later, Reid told then-Gov. Kenny Guinn during a meeting in Washington that Loux should be let go because he was too much of a lightning rod on the Hill, hampering the senator’s efforts to get the state money to fight the dump, according to a Sun story at the time.

Somehow, he always managed to survive.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy