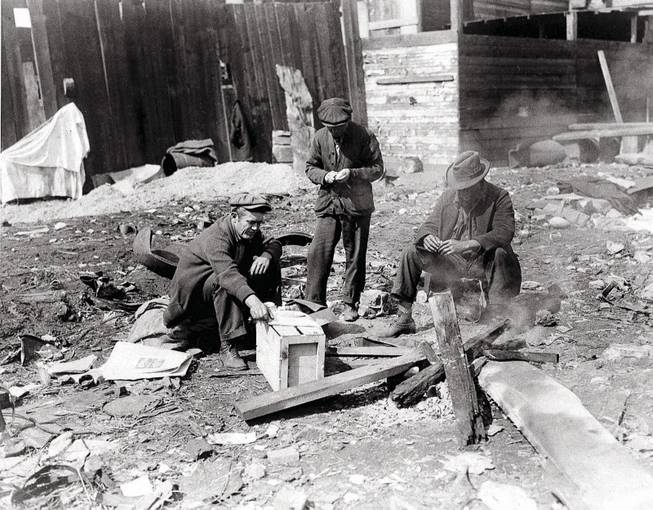

ASSOCIATED PRESS FILE

Three unemployed men start a fire for cooking in a vacant New York City lot, where they lived when not searching for work during the Great Depression in 1932.

Thursday, Feb. 5, 2009 | 2 a.m.

As senators wrangle this week over Washington’s plan to stimulate the economy, the debate is laced with competing interpretations of something that happened seven decades ago: the Great Depression.

Related story

Sun archives

Sun Blogs

Many Democrats believe government’s spending under Franklin Roosevelt helped the nation climb out of the Depression. They support President Barack Obama’s plan to inject $900 billion into the economy.

Other lawmakers, mainly Republicans and notably Nevada Sen. John Ensign, believe the opposite. “All the government spending did not take us out of the Depression,” Ensign said. They want to rein in Obama’s stimulus package and provide more tax breaks so the private sector can reverse the downturn.

So which view of the Depression is correct?

Let’s start with the president who occupied the White House when the Depression began, Herbert Hoover.

Did Hoover sit on his hands, predicting an imminent recovery, as liberal politicians and economists say?

Or, was he, as Ensign said, “very much an interventionist”?

Ensign argues he “raised taxes, he increased spending — very much tried to meddle in the economy,” without success.

Brian Balogh, a 20th-century historian at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs, said Hoover often did assure the public that the Depression was in retreat, but he did so while trying a number of things to revive the economy.

Hoover created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which directed money to state and local governments to continue with large capital projects. He also raised tariffs on imports.

But the Depression continued.

William Gale, an economist at the Brookings Institution, said the judgment of Hoover’s actions doesn’t come down to a matter of “too much or too little; it was the wrong thing. It’s not a matter of do you intervene or not intervene. It’s whether you do something intelligent or not.”

Ultimately, Hoover was “unwilling to have the national government intervene directly in the economy,” Balogh said. He “drew the line at direct work relief, at creating federal jobs for people.”

Raising tariffs, in fact, turned out to be counterproductive. It kept countries that exported to the United States from earning enough dollars to pay their debts, which in turn led to big losses for the banking industry, said James Galbraith, economist at the University of Texas’ LBJ School of Public Affairs.

Historians and economists are less in agreement about the effects of the man who replaced Hoover, Franklin Roosevelt, and the effects of his New Deal.

Launched in Roosevelt’s first term, the New Deal included enormous deficit spending to pay for new agricultural programs and emergency relief and work relief programs, in addition to reforms to banking and industry.

Did it work? Here’s where things get murky.

Economists and historians agree that under Hoover, unemployment climbed to record levels, 25 percent, and then steadily declined after FDR took over in 1933.

By the end of the 1930s, unemployment was down to 10 percent or less. “In fact, Roosevelt did spend his way out of the Depression,” Galbraith said.

But other economists argue that unemployment actually stood much higher at the end of the decade — at 15 percent. And at 15 percent, they say, the country was still in a Depression even if far more Americans had jobs.

Two points are worth making here.

One, even if unemployment stood at 15 percent, the level was in fact down 10 percentage points from the beginning of FDR’s presidency. So does that mean FDRs policies succeeded or failed? That debate continues.

Two, the difference between 10 percent and 15 percent unemployment levels comes down to 3.5 million jobs. Those jobs were temporary, created and paid for by the federal government.

Liberal economists tend to count those jobs because the workers were, in fact, working.

Conservatives tend not to count them, arguing that government-funded temporary jobs are not a true reflection of the strength of the economy and should not be considered a measurement of the New Deal’s effectiveness.

Incidentally, the current national unemployment rate, as of December, was 7.2 percent.

Another point of contention about the Great Depression is something that occurred in FDR’s second term. Roosevelt campaigned in 1936 on ending deficit spending and returning to the policies of a balanced budget. After reining in spending by repealing many welfare programs, however, the economy slid in 1937. So was it a mistake to halt deficit spending?

Again, the debate continues.

As the 1930s drew to a close, FDR’s treasury secretary, Henry Morgenthau, told Congress that despite spending more money than ever before, the federal government had not solved the riddle of the Depression.

Some conservatives have seized on that comment today as evidence that Obama’s plan will fail to end the recession.

Most experts do agree that a lesson of the Depression is that the government must act aggressively to stop a downward spiral caused by an absence of liquidity.

“The lesson of the past is the government didn’t respond enough to avert the banking crisis. We can’t just stand by and let the financial system collapse,” Gale said. “If the economy is the engine, the financial system is the oil. If you lose the oil, then the engine dies — and a particularly nasty death. That lesson has been learned.”

The Depression ended in the first half of the 1940s as the government spent unprecedented sums to finance World War II. Suddenly jobs were more plentiful than workers. The war had provided economic stimulus far greater than anything under the New Deal.

Some economists say the lesson here could be that the New Deal had not rescued the economy because the government didn’t spend enough money in the previous decade — an argument in favor of massive and prompt federal spending by Washington today.

No one is talking about spending nearly as much of the current gross domestic product as was spent by the government during World War II, which could be seen as good thing or as a bad thing, depending on your view.

After the war, the nation enjoyed an economic boom caused in part by pent-up savings from the war years, Galbraith said. People working during the war earned money they couldn’t spend because purchases were limited by rationing, so “the war made it possible for American households to accumulate savings,” Galbraith said.

One final argument also makes the rounds these days, championed by Christina Romer, chairwoman of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers.

She says the recovery was largely due to monetary policy. Romer has concluded that a doubling of the dollar-gold exchange rate had the major impact. Gold bought twice as many dollars, which led to an increase in the money supply, boosting bank deposits, investments and lending.

Pete Klenow, an economist at Stanford, said despite all the talk about lessons learned from the Depression, the nation still doesn’t understand enough of why recessions occur, and therefore both Republicans and Democrats might have the answer.

The economy would probably be well served by a wide range of solutions, including tax cuts and massive spending, he said.

“The Great Depression was a long time ago,” Gale said.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy