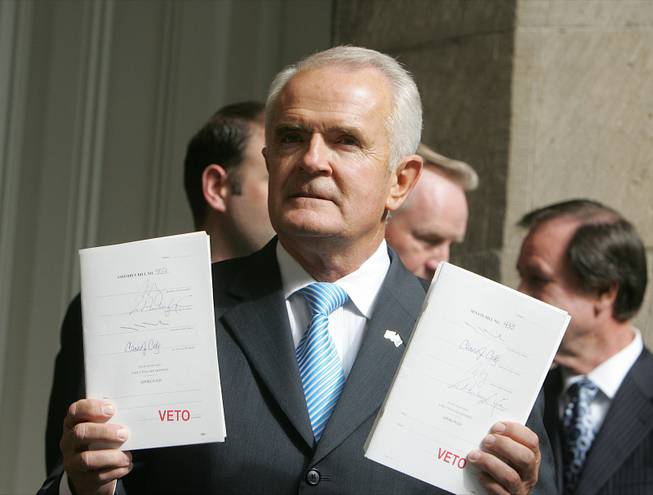

AP Photo/Brad Horn, Nevada Appeal

Gov. Jim Gibbons holds up AB552 and SB433 after he vetoed the bills on the Capitol steps in Carson City at the Nevada Legislature on Thursday, May 28, 2009.

Sunday, May 31, 2009 | 2 a.m.

In Today's Sun

Sun Archives

- With 31 vetoes, a look at what the governor opposed (5-29-2009)

- Assembly's override puts tax package into law (5-29-2009)

- The JIm Gibbons voters elected (5-29-2009)

- Gibbons' veto stings educators at rally (5-28-2009)

Sun Coverage

Vetopalooza.

That is what punch-drunk legislators and lobbyists are calling the flurry of vetoes by Gov. Jim Gibbons as the legislative session nears its end.

The vetoes have come in batches big and small, 42 as of midday Saturday, with notes attached that are at turns principled and petulant.

Gibbons has set a record, beating out early statehood Gov. Henry Blasdel, who rejected 33 bills during the 1864-65 Legislature. His vetoes have run the gamut, from the budget and the taxes needed to pay for it, to help for workers who get injured, to a hunting apprenticeship program, to tougher reporting requirements for hospitals (see story, page 8).

Like so much about Gibbons — his rodeo lifestyle, his laissez faire approach to governing and his uncompromising conservative ideology — no one has seen anything like it.

“I’ve been here 29 years, and normally a governor communicates with the Legislature during the session about what he likes and what he doesn’t, and there’s a compromise,” said Danny Thompson, a former assemblyman and head of the state AFL-CIO.

“He’s not engaged in the process. If you talk to anyone here, they’ve seen nothing like it. It makes no sense,” Thompson said.

Capital observers cite two main reasons for all the vetoes: The governor’s ideology, which dictates that government should offer light oversight of the marketplace; and open hostility between the Democratic-controlled Legislature and the governor.

In an e-mail exchange, Dan Burns, the governor’s spokesman, said the issue is not vetoes, but rather, bad legislation.

“If the Legislature would stop sending over so many bad bills, the governor would not have to veto them. A ‘bad bill’ has new or higher taxes, new or higher fees (without the support of the industry or people paying the fee), or is simply bad public policy for government. Each bill is considered on its own merits,” Burns wrote.

He continued: “The governor takes no pride in breaking a record for vetoes ... The governor takes pride in standing up for what he believes in and in keeping the promises he made to the people who voted for him. If that means a veto, then so be it.”

Gibbons might have felt slighted

But a Republican lobbyist who served in the administration of Gov. Kenny Guinn, the two-term Republican, said Guinn would frequently call over to the Legislature to voice his views about bills and suggest compromises to avoid vetoes.

The problem with vetoes as a strategy is that they are accompanied by the risk of overrides. As of midday Saturday, the Legislature had overridden four vetoes, but many more overrides are coming.

The overrides can make a governor appear weak and rob him of political capital, which Gibbons had little of to begin with. There was talk among Republicans of switching votes to help Gibbons sustain vetoes and thus prevent further embarrassment.

Like so many others, the Republican lobbyist asked for anonymity because he fears, well, vetoes in retribution.

This governor has made few calls to the Legislature and is rarely, if ever, in the building. His relationship with the Legislature, including veteran Republicans, is distant at best.

Senate Minority Leader Bill Raggio, R-Reno, acknowledged that Gibbons has been the least engaged of any governor since his tenure began 3 1/2 decades ago.

But he didn’t lay all the blame on Gibbons.

“The Legislature started out here extremely critical of the governor. I don’t think extreme criticism is helpful to the process,” he said. “I don’t think the Legislature, particularly Democratic leadership, made him feel very welcome.”

The governor is giving his veto stamp such a workout that lobbyists and lawmakers were nervous Saturday about whether their bills would suffer the fate of so many others.

What is particularly unnerving, they say, is that his staff members are in the dark about what will get vetoed, and they don’t have any guiding principle for what will get the stamp.

“All businesses, before they ask us to pull the trigger on one of their bills, have to make a phone call to the governor and make sure he’s not going to veto it,” said Sen. Bob Coffin, D-Las Vegas.

A few of the vetoes have confused legislators.

In some cases, his argument seemed to be that if he could not have the whole bakery, he does not want a loaf of bread.

Assembly Bill 463 would limit the use of pricey consultants in an effort to improve transparency and save the state money. Gibbons vetoed it because it continued to allow consulting contracts for the higher education system and the Legislature.

The Assembly overrode the veto easily Saturday.

Another veto of the “No half loaf for me” variety was his rejection of Assembly Bill 458, which would create a rainy-day fund for K-12 education and take some money from redevelopment agencies for schools. Gibbons called it a “laudable goal.”

“I agree that such a fund should be created. However, I disapprove of this bill because it does not create similar funds for other areas of state government,” he wrote.

Assembly Speaker Barbara Buckley, D-Las Vegas, on the floor of her chamber, was incredulous about the veto of the education rainy day fund. “It is incomprehensible to me that the governor would veto this bill.”

The Assembly overrode the veto easily.

Oddly, Gibbons allowed another bill, AB165, which would bolster the state rainy day fund, to become law without his signature.

Some, you’d think he’d like.

There were several bills that would seem to appeal to a conservative such as Gibbons, but they got the veto stamp anyway.

A favorite program of the National Rifle Association would create a hunter apprenticeship program.

Assembly Bill 446, sponsored by Buckley, would have required the budget to include a summary of long-term performance in such areas as public schools, the university system, human services, public safety and health in an effort to improve accountability.

Gibbons, in his veto message, said the start-up costs would be $347,000, and it would require an annual allocation of $141,000. Without that money, the governor said, the Administration Department could not perform the tasks outlined in the bill.

Another vetoed bill conservatives might have liked: Newspapers currently publish the property tax rolls, a source of easy advertising revenue. Assembly Bill 307 would have permitted governments to publish the information on the Internet to save money.

In vetoing the bill, the governor said access to the Internet in large portions of rural Nevada is not available or available only in dial-up form. Deputy Chief of Staff Mendy Elliott said Las Vegas Review-Journal Publisher Sherman Frederick was lobbying the governor on the issue.

The first round of vetoes came on May 21.

Among others, no to a voter-approved gas tax increase in Washoe County: The ballot question they voted on was confusing, Gibbons said.

No to an increase in water fees paid to the state engineer: “I am not aware of any significant support by industry.”

No to a bill expanding the Consumer Health Assistance Office: “It’s not an ‘essential’ government service.”

Last week, Gibbons vetoed Senate Bill 283, which would allow for domestic partnerships for straight and gay couples. The Senate overrode his veto, and the Assembly was expected to follow suit. Thursday was the big day. He vetoed eight budget bills and 12 others.

By Saturday afternoon, Gibbons’ total was 42.

The Legislature still has about 36 hours to get bills to him, and to override.

Sun Capital Bureau Chief Cy Ryan contributed to this story.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy