Wednesday, Nov. 18, 2009 | 2 a.m.

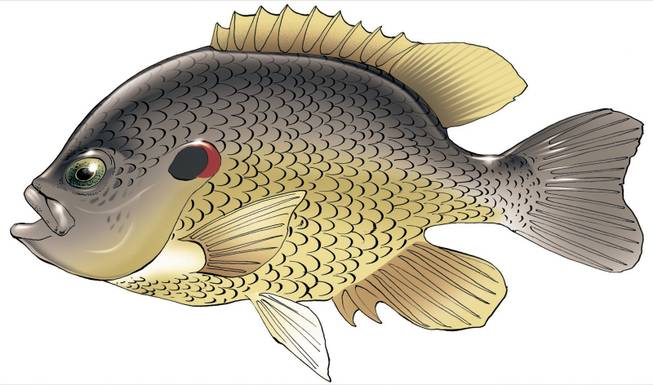

Redear sunfish

- Known aliases: Chinquapin, Shellcracker, Mason Bream, Tupelo Bream, Mongrel Bream, Yellow Bream, Stumpknocker, GI (Government Improved) Bream

- The general dorsal coloration is olive with darker specks.

- Redear depend largely on mollusks for food and don’t compete heavily with insect-eating fish. Redear have highly developed grinding teeth — or shell crackers — in their throats. The teeth crush snails, their fare of choice.

- Redear are typically found in the southeast United States, but have been introduced into several states. Their normal range is from the Mississippi River basin in Indiana and Missouri south to the Gulf Coast.

- Redear sunfish can exceed 10 inches in length and weigh over 4 pounds, making them popular sport fish.

- Sources: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

Refresher course: The mussel danger

Mussels absorb toxins and heavy metals from the lake water and later expel them as highly concentrated pellets. Toxins could then enter the food chain when bottom dwellers eat the pellets. Quagga mussels could also produce more favorable conditions for algae that can contaminate drinking water with toxins.

Sun Archives

- Quagga mussels a toxic threat (11-9-09)

- The man dedicated to saving the lake from little invaders (11-9-09)

- Wary of invasive species, hatchery suspends operations (1-20-2009)

- Mussels’ last meal (6-20-2008)

- Get rid of pest? Not if it turns tap water pink (7-21-2007)

- Mussels now contained but need monitoring (1-18-2007)

- Lake Mead mussels identified as quagga, not zebra (1-13-2007)

Sun Topics

Beyond the Sun

- Wikipedia: Redear sunfish

Nature appears to have a brightly colored solution to the quagga mussel invasion at Lake Mead.

The redear sunfish is waiting in the wings to be introduced as the potential savior of the Las Vegas Valley’s main water source.

UNLV biologist David Wong, the region’s chief quagga fighter, has long suspected that fish appetite could be the best answer to the clam infestation. He’s as much a fish expert as he is a mussel expert, having earned a bachelor’s degree in fisheries and a doctorate in aquatic ecology before taking on invasive mussels.

He keeps a fish tank in his office that’s home to a small colony of live quagga mussels, a couple of bamboo plants and one unnamed red carp. From time to time, Wong gets to see a tiny scrap of gray flesh hanging from the carp’s golden mouth, evidence that the fish ate another of Wong’s quagga mussels.

To get the carp to eat the quaggas, however, Wong has to “keep him hungry.”

Like Wong’s carp, plenty of fish in Lake Mead will force themselves to eat quaggas if they’re starving. But, as Doug Nielsen, spokesman for the Nevada Department of Wildlife, which manages the fish in Lake Mead, puts it: “There’s a variety of food already available in those waters that don’t come with a very, very sharp shell,” mainly lots of smaller fish.

The redear sunfish is undaunted by the quagga’s razor-sharp and rock hard shell. Its most common nickname in its native southeastern U.S. is “the shellcracker,” after all.

The redear are equipped with a set of movable plates in their throats that make it easy for them to devour clams. In lab experiments, redear sunfish have eaten nothing but quagga mussels for months and were no worse for wear.

Lake Mead, unfortunately, is one of the few areas on the lower Colorado River that don’t have a measurable population of the redear. But the fish could thrive in Lake Mead if the lake were stocked with them. There are plenty of quaggas in many parts of the lake the redear could feed on if they can avoid the many predatory sport fish that also live there.

Not rushing to stock

Before setting off the feeding frenzy, however, researchers and wildlife managers need to evaluate experiments in which redear sunfish are being introduced into lakes and canals in California and Arizona. Wong hopes to see results from his and other research in the Southwest within the next year or two, by which time the quaggas in Lake Mead will have reached a critical mass capable of affecting water quality.

Wong and his colleagues don’t yet have a good estimate as to the number of redear it would take to control the lake’s quagga population. They do know, however, that it would take a lot, and that brings up the main reason bucketfuls of thrashing redear aren’t being dumped into the lake: Researchers and wildlife managers don’t know how a massive influx of redear (or any other new fish species) would affect the lake’s ecology.

Redear study elsewhere

Redear are fairly common in the river below Davis Dam and Lake Havasu, where they munch happily on quaggas but haven’t had an appreciable effect on the mollusk’s population, according to John Sjoberg, a state biologist who oversees the Lake Mead fishery.

“If the redear were the end-all be-all you’d think they would be multiplying in great numbers,” Sjoberg said. “They aren’t ... The quaggas are already widespread (in Lake Mead) but we have the time to make an informed decision before we start pitching stuff in the lake.”

Wong is right in the middle of that investigation. He has advised researchers from Arizona to Colorado on sunfish versus quagga experiments. He’s currently involved in a California lake experiment that looks at redear consumption of quaggas in the wild and whether the fish have any detrimental effect on that lake’s ecology.

Before Wong and other researchers can recommend that the National Park Service and Nevada Department of Wildlife start stocking Lake Mead with redear, they need to first ensure the fish won’t cause any significant drops in the populations of the important fish species that live there.

Mead’s a bass lake

Lake Mead, with its 300-plus days a year of sunshine, is a major sport fishing destination. The most popular fish in the lake are striped bass, largemouth bass and smallmouth bass, Fish and Wildlife spokesman Doug Nielsen said. People fly in from all over the world to try to catch the kindergartner-sized fish Lake Mead can support, he said. The record striper in Lake Mead is 63 pounds and it’s fairly common to catch 20-pound fish.

If the lake can support lots of bass and lots of redear too, though, that could be a boon to the sport fishing industry.

“It’s a matter of preference, Nielsen said. “Some people like sunfish and some don’t. We have some people who look just for carp and others who consider them trash fish. Some people go to Laughlin specifically to fish for redear sunfish. Lake Mead is known for its bass.”

In a few years, however, it could be known as a great place to catch redear sunfish too.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy