Friday, Feb. 12, 2010 | 2 a.m.

Related Document (.pdf)

Sun Archives

Sun Coverage

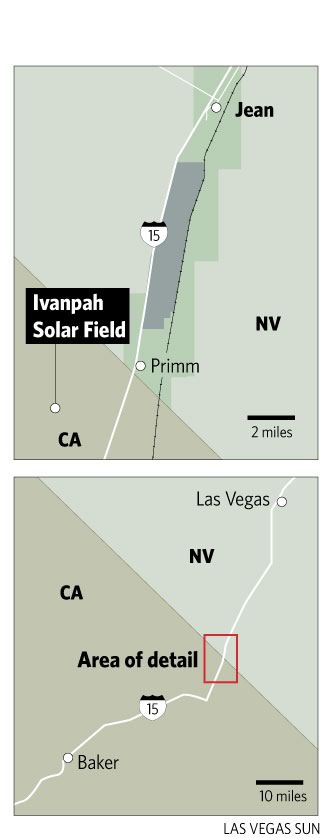

Hundreds of out-of-work Las Vegas construction workers have been waiting for a chance to start building a giant solar plant in California, just southwest of Primm, but San Bernardino County officials’ objections are putting those jobs on hold if not jeopardizing them entirely.

The project’s problems may serve as a preview of the hurdles that other solar plants planned for Southern Nevada will have to clear.

San Bernardino County’s Board of Supervisors filed a formal objection Thursday to the Ivanpah Solar project planned for 4,000 acres of federal land about 5 miles south of the Primm Golf Course. Officials complained the solar plant would financially harm the county, reduce the quality of life and not provide enough jobs for San Bernardino residents.

Because California gives tax breaks to solar developers, the county won’t get much revenue from the project. The land and mirrors that the plant would use are exempt. At best, the county could get some revenue from the tower used to generate steam for electricity and outbuildings, says Andy Silva, spokesman for county Supervisor Brad Mitzelfelt, an outspoken opponent of the project.

Although the plant is expected to create about 1,000 short-term construction jobs and about 85 long-term jobs, most of the workers are expected to come from Las Vegas and Primm, so most of the $250 million in wages would be spent in Nevada. The California town closest to the site is Baker. It’s about the same distance from the site as Las Vegas is, but with Baker’s population of about 1,000, it’s unlikely many would fit the bill for jobs at the plant.

San Bernardino County also would lose property tax revenue because of mitigation requirements.

The plant’s developer, BrightSource Energy, has agreed to purchase 12,000 acres in the county and turn them over to the federal government to offset the loss of desert habitat caused by its development. This would cause the county to lose the land’s tax revenue. Economic growth would be limited because the land would be off-limits to development.

The county is still trying to put a number on its projected net loss, Silva says.

BrightSource is not the only developer planning to build in San Bernardino. Several very large solar energy projects are planned there, and BrightSource’s mitigation plan is expected to be the norm for most or all of the renewable energy projects proposed.

“If they all have to do that 3-to-1 mitigation ratio, you could be looking at locking up the entire desert,” Silva says.

The objection could be a game changer for BrightSource. The county does not have the authority to nix the project, but it could pressure the Bureau of Land Management or California Energy Commission to change the mitigation plan or reduce the size of the project.

That would be another setback for BrightSource, which had a major project in that area tabled because Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., wanted the land for a recreation area.

The Ivanpah project has faced other challenges. It was slated to begin construction by now, but that was delayed because the BLM and California Energy Commission asked for major changes. The environmental impact statements raised concerns about major habitat loss for rare plants and animals on wide swaths of land.

The company released new plans to shrink the project’s footprint by 12 percent, reduce the electricity generating towers from seven to three and install tens of thousands fewer mirrors to avoid the most sensitive areas. Construction is expected to begin by the third quarter of this year.

Silva says county officials don’t want to see Ivanpah Solar, or any solar project in San Bernardino, canceled. But they also don’t want any of these projects to be detrimental to the county.

“This is the first megaproject out of the gate, and the whole industry is watching this,” Silva says. “The state and federal governments are overseeing this, but we’re going to get the impacts, and we want to make sure there’s a net benefit.”

They would like to see the mitigation plan changed. Instead of BrightSource buying up private land, the county would like the government to allow the developer to write a check to existing habitat preservation and tortoise protection programs on public land.

Officials would also like solar developers to pay for the increased support services near their development. The closest San Bernardino County fire station is 40 miles from the planned site. The county would like the developers to pay building costs for one closer to the plant.

BrightSource representatives were unavailable to comment Thursday because of corporate board meetings, but spokesman Keely Wachs says the company is addressing all the concerns through the public comment process as intended under the Environmental Protection Act.

“We’re having very productive conversations with the county about how to maximize economic development opportunities around the Ivanpah project, and we share their concerns around the amount of land required for mitigation,” Wachs says.

Although some of the objections the Ivanpah solar project has faced are unique to its site, it could be a harbinger of things to come in Nevada. The Ivanpah project is the first large-scale solar project on BLM land to get this far and some of the same environmental, economic and community effects could become problems in Searchlight or Beatty.

If a developer in Amargosa Valley, for example, was required to purchase private land to offset the footprint of a solar array, such a purchase could eat up farmland, reducing county and state tax revenue.

Nevadans have wrangled over whether the short-term jobs and boost in ego from becoming the alternative energy capital of the U.S. would be worth losing a lot of the state’s desert to solar arrays and transforming its mountaintops with wind turbines. Rural residents fear for their water supplies, scenic views and livelihoods. Off-roaders fear losing recreational areas.

Nevada, like San Bernardino County, will soon be weighing the losses and benefits.

“For people who live in the desert, it’s a lifestyle issue as much as a money issue,” Silva says. “Whether you’re a Sierra Club member or off-roader, you’re out there because you love the desert and want to be able to enjoy it, and we’re afraid (solar plant mitigation) could restrict that multiuse on this land.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy