Saturday, Jan. 16, 2010 | 2 a.m.

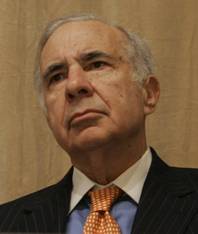

Carl Icahn

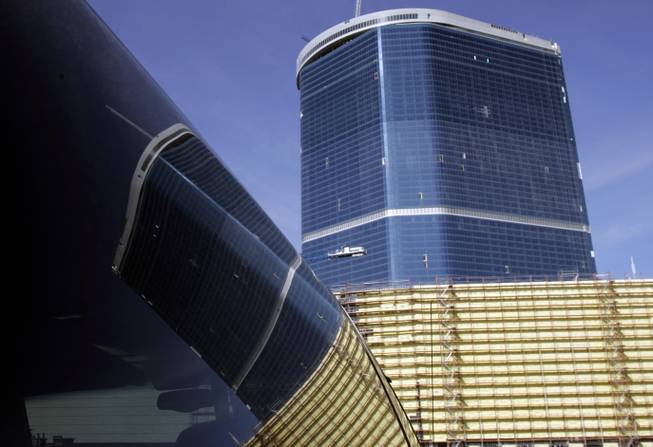

Fontainebleau

Sun Archives

- Deadline for Fontainebleau bids set for Friday (1-11-2010)

- Fontainebleau judge details guidelines for credit bid (12-8-2009)

- Fontainebleau: Half-built bargain bid up by billionaire (12-7-2009)

- Fontainebleau lenders sue construction companies over liens (11-27-2009)

- Fontainebleau retail component seeks bankruptcy protection (11-27-2009)

- Contractors make another bid for Fontainebleau (11-26-2009)

- Penn National’s bid sets up auction for Fontainebleau (11-5-2009)

- Fontainebleau subcontractors organize to finish project (11-17-2009)

- Fontainebleau developer plans appeal of rulings (11-2-2009)

- Subcontractors fall short in effort to move Fontainebleau case (10-26-2009)

- Executive named examiner in Fontainebleau bankruptcy case (10-16-2009)

- Fontainebleau president among execs leaving project (10-15-2009)

- Fontainebleau a symbol of bad timing, not the only victim (10-12-2009)

- Fontainebleau judge wants quick sale of bankrupt project (10-2-2009)

- In reversal, Fontainebleau lenders suggest liquidation (9-25-2009)

- Fontainebleau: Bank no longer ‘seeking to destroy’ project (9-17-2009)

In years past, casino bankruptcy auctions generated a frenzy of activity, with multiple bidders emerging at the last minute with the promise of cash at the other end of a cell phone. Those with little money or credibility would quickly drop out, leaving a few usual suspects vying for a shot at a bargain buy.

There may be no such party for the bankrupt, unfinished Fontainebleau Las Vegas resort that is sought by billionaire investor Carl Icahn.

On Friday — the deadline imposed by the bankruptcy court for competing bids — additional bidders quietly surfaced, according to a source close to the situation. But whether they would qualify could not be determined.

So Icahn, the front-runner for Fontainebleau with a starting bid of $156.2 million, may end up holding the bag.

And what a bag it is. The resort, a spectacular victim of the downturn, is no slam-dunk casino bargain.

Some experts think it will cost $1.5 billion just to finish the resort, on which construction stopped in the summer after lenders pulled $800 million in financing in the worsening economy and forced the property into a bankruptcy filing.

Fontainebleau is believed to be the most expensive, half-built building in the nation. That’s uncharted territory for any buyer, including Icahn.

Icahn has maybe three options.

• He could spend the $1.5 billion that Penn National Gaming — a company that pulled out of the running early in the bidding process — estimated it would take to finish the job. Penn did months of homework investigating the project and crunching numbers on what it would take to generate a profit on the resort. That kind of money, the company said, would yield a luxury resort the caliber of Mandalay Bay — nicer than most but no Wynn Las Vegas. Outfitting the property on the cheap and filling it with chains like Cheesecake Factory and Outback Steakhouse, while nice restaurants, wasn’t going to do it for Penn.

• Icahn could spend less than that to complete the building. Some observers have theorized that subcontractors might agree to finish the building at lower rates given that some money is better than none. Cost cutting, when done with a deadline and a finely tuned blade, might yield a more cost-effective structure.

• Third, he could opt to not finish the building and simply sit on his purchase, biding time until the economy improves. That might be the most cost-effective strategy, but it might be the worst outcome for Las Vegas because it would add to its recession-fueled blight. Across Las Vegas Boulevard, the former site of the New Frontier and the future site of the Echelon resort sit vacant, gathering tumbleweeds.

And yet, there’s an argument to be made against opening new hotel rooms. Fewer resorts could be good for Las Vegas because it would mean less competition for visitors.

Icahn, who gives few interviews, isn’t talking about his plans for Fontainebleau.

But his biggest coup in the casino industry might shed some light on his thinking.

Icahn gained control of the Stratosphere in 1998 after a well-timed purchase of the property’s bonds at fire-sale prices, which enabled him to take over the property in bankruptcy. With an initial investment of less than $100 million and another $75 million to add a hotel tower and other amenities, Icahn turned the money-losing Stratosphere into a profitable resort that benefited from a boom in tourism lasting nearly a decade.

Icahn sold the Stratosphere and a group of other casinos to a group of Goldman Sachs real estate funds at the peak of the real estate market, making close to $1 billion on the deal.

The late Bob Stupak built the Stratosphere with too much debt and at the tail end of a string of resort openings in Las Vegas. Critics said it wasn’t a game-changing property but an also-ran in a dicey part of town north of Sahara Avenue. After Icahn bought and expanded the property, the Stratosphere gained a reputation as a casino that offered a good value for the money — a step above some of the older, more run-down properties but less expensive than high-end megaresorts and others that had undergone pricey upgrades.

With lower and middle classes flocking to Las Vegas during boom years, Stratosphere was in the right place at the right time.

Perhaps Icahn wants to create a mid-market resort out of Fontainebleau — a strategy that might appeal to bargain-hunting tourists soured on fancy hotels. The property might complement the nine casinos Icahn is acquiring as part of Tropicana Entertainment, which includes the MontBleu resort in Stateline, Tropicana Express in Laughlin and Tropicana resort in Atlantic City. (The Tropicana in Las Vegas, acquired by another buyer out of bankruptcy, wasn’t part of the deal.)

Or perhaps Icahn is bluffing.

In one sense, he has shown his hand. Icahn has gone where other investors have feared to tread — making a fortune on the business missteps of others.

He’s snapping up the Tropicana chain for $200 million — $800 million less than what it was expected to fetch during the boom economy.

Fontainebleau’s developers sunk $2 billion into the property — a mostly finished structure with incomplete interiors. But that was money spent in another era.

While $156 million sounds like a steal, it might still be too much for others — without Icahn’s knack for timing — to stomach.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy