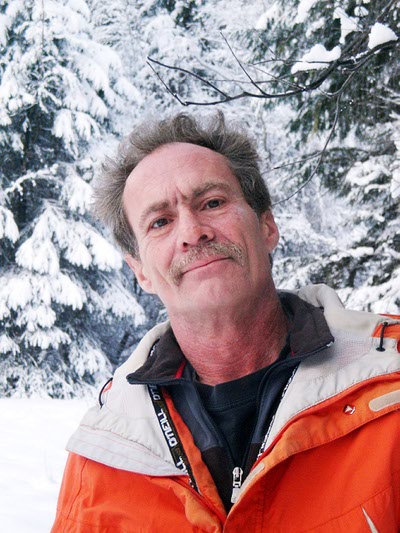

Courtesy of Bruce Bauer

Dr. Lester Bauer was slain in 1994. His killer is still appealing his death sentence.

Sunday, Oct. 31, 2010 | 2 a.m.

It took a Clark County jury only four hours in 1997 to decide Donald Sherman should die for using a hammer to brutally kill a retired doctor as he slept, but Sherman is alive 13 years later as his appeals in state and federal courts run their courses.

The case was kept alive just this month by yet another ruling.

That explains the anger in the voice of the victim’s son, Bruce Bauer, as he thinks daily about what happened to his father, Dr. Lester Bauer. He bristles at how long it’s taking for justice to be served. The younger Bauer, 53, is so upset he considers leaving his dream job as a commercial fisherman in picturesque Haines, Alaska, and chaining himself to a tree, a parking meter or another immovable object in front of the courthouse in Las Vegas in protest.

“If you’re going to give somebody the death penalty, you need to back it up,” Bauer said. “I blame Nevada for not implementing the law. They should just quit giving death sentences in Nevada because it’s a waste of time. This is just driving me nuts.”

Jurors were told that Sherman murdered the doctor after a bitter breakup with the doctor’s daughter, who had been supporting Sherman financially.

That Sherman is alive is hardly unusual. Of the 83 people on Nevada’s death row at Ely State Prison, more than half have been there longer than he has. One, Edward Wilson, has been there since 1979, as he continues to appeal constitutional questions to the Nevada Supreme Court.

More often than not, death row inmates have delayed death by lethal injection because they haven’t exhausted their appeals. It’s telling that of the 12 people who have been executed in Nevada since 1979, 11 waived appeals.

Relatives of murder victims and others who favor the death penalty say justice isn’t being served because prolonged appeals traumatize victims’ loved ones and cause the public to lose faith in the legal system.

Death penalty foes have different complaints about the appeals process. The National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty says studies show such cases, from arrest to execution, cost taxpayers $1 million to $3 million each, draining resources from public safety, schools and other needs. The coalition says by comparison a sentence of life in prison costs about $500,000 on average.

No one appears completely satisfied with the status quo. But there may be little Nevada can do to shorten the appeals process without cooperation from outside influences, including Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court.

A national study for the Justice Department in 2005 said it takes more than 12 years on average to execute someone after sentencing. Nevada, one of 14 states involved in the study, was praised for having one of the swiftest periods from the initial appeal to when the Nevada Supreme Court — the state court of last resort — issues its ruling. Nevada’s average is about 20 months, second behind Virginia’s average of about 10 months. But that does not conclude the appeals process.

The study’s authors, City University of New York professors Barry Latzer and James Cauthen, said a significant chunk of the time it takes for appeals to be resolved is due to U.S. Supreme Court mandates. The high court has ruled that death penalty cases merit more opportunities for appeal than lesser criminal sentences, a form of “super” due process. That means more instances of cases in which a convict can allege that ineffective defense attorneys and other constitutional errors were committed. And where it can really bog down is in federal court.

As Edie Cartwright, spokeswoman for the Nevada attorney general’s office, says: “Inmates constantly develop new theories as to why their death sentences should not be carried out. Our state is no different from others in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. This process just takes a long time. Our neighboring states are having the same difficulties as Nevada.”

This frustrates Steve Owens, Clark County’s chief deputy district attorney who oversees death penalty cases. He said some death row inmates have been allowed to file four or more appeals. And the paperwork can be voluminous. He recalled one appeal contained 369 pages of arguments and 4,971 pages of exhibits.

“We’ve got some tough provisions in place, but it takes time to litigate these cases,” Owens said. “One thing I’d like to see is a limit on the number of pages that can be filed because 369 pages is absurd. I’d also like to see the federal courts not send these cases back so many times” to state courts, he said.

He wants courts to use more discretion to summarily dismiss petitions rather than have them linger in the system. From Owens’ perspective, too much time is spent dissecting cases in a bid to find errors.

“It shouldn’t take 20 or 25 years,” he said. “There should be a more standardized way of doing this.”

But Federal Public Defender Franny Forsman, whose Las Vegas office defends death row inmates in federal court, said the lengthy appeals process could be streamlined if more money and resources were provided to public defenders at the trial. That could help eliminate many of the constitutional errors she said occur because of ineffective counsel, lack of investigative resources or other shortcomings.

Federal public defenders generally have access to far more money and resources than county public defenders, which helps explain the high volume of detail that goes into the appeals process.

“There have been facts that have turned up in the appeals process that were never known before,” Forsman said. Although she favors abolishing the death penalty, it also makes sense to Forsman that the appeals process takes as long as it does.

“The good thing about the system is that it’s careful before it puts someone to death,” she said.

Another death penalty foe, Nancy Hart of the Nevada Coalition Against the Death Penalty in Reno, defended the appeals process because of the complexity of the cases. There are times, she said, when it is not learned until years after the trial that a death row inmate had a mental health problem that could have affected the case.

An effort by the Innocence Project, a national litigation organization that seeks to overturn the sentences of wrongfully convicted individuals through DNA evidence, underscores the need for “getting it right” in death penalty cases, said professor James Richardson, director of UNR’s Judicial Studies program.

“The fact that nearly 300 death row inmates have been proven innocent by that effort, which has also demonstrated the severe problems with eyewitness testimony, is reason enough to take time when putting people to death,” Richardson said.

From Bruce Bauer’s perspective, though, having to live through his father’s murder in his Sun City Summerlin condo is a gut-wrenching experience. He cried at the two-week trial, during which he lost 35 pounds. He went through intensive counseling afterward and suffered through a divorce. Bouts of drinking followed, he said, along with stress that he blames at least in part for his prostate cancer.

“It’s kind of a mental prison,” he said. “You just try to shake it.”

A close look at Sherman’s file shows how a death penalty case can drag on.

It began in 1994, when the then 30-year-old assailant killed Lester Bauer and fled in the victim’s Acura Integra. Sherman was arrested in Santa Barbara, Calif., the night after Bauer’s body was found. But the murder — the first in Sun City Summerlin — sent shivers throughout the retirement community.

Sherman was on parole for another murder in Idaho in 1981, when he was 17 and shot and killed a shopkeeper during a robbery attempt while high on LSD.

Convicted of Bauer’s murder by a Clark County jury and sentenced to death in 1997, Sherman exercised his right to appeal the death penalty. That appeal was rejected by the Nevada Supreme Court in 1998 and the U.S. Supreme Court in 1999. But that was just the opening round.

• Later in 1999, Sherman filed in District Court in Clark County a petition for writ of habeas corpus — a way of claiming wrongful imprisonment because of a purported error in court.

• He filed a supplemental petition in 2000, but it was denied that year by District Court.

• The Nevada Supreme Court denied the same petition in 2002, refusing to buy Sherman’s argument that the trial judge erred by improperly quoting from the Bible to show a juror that the death penalty is permitted. The court found that the Bible remark was inappropriate but didn’t affect Sherman’s sentence.

• Later in 2002, Sherman filed a similar petition in federal court in Las Vegas.

• He was appointed a federal public defender in 2003.

• In 2005, an amended petition was filed on his behalf in federal court, raising constitutional issues that had not been considered.

• A federal judge in 2006 denied a motion by the state to dismiss the petition, instead opting to postpone the case indefinitely.

• In 2007, the Nevada Supreme Court agreed to reconsider Sherman’s petition because of procedural issues.

• The Supreme Court rejected the petition in May and denied a motion for rehearing in July.

• A motion to reopen the habeas corpus proceeding was filed in federal court in September. On Oct. 7, U.S. District Judge Larry Hicks reopened the case, allowing Sherman to file an amended petition with new arguments.

If it were left up to Bauer, Sherman would have been required to file all of his appeals a decade ago after the U.S. Supreme Court denied the initial appeal. And Bauer also would have required Nevada law enforcement authorities — whether the district attorney, attorney general or Nevada Corrections Department — to keep him updated on Sherman’s appeals, information he said he never receives.

“I want to stay on top of the situation because I owe it to my father and I owe it to my family,” Bauer said.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy