Wednesday, April 27, 2011 | 2:05 a.m.

KSNV: DesertXpress EIS

KSNV coverage of announced completion of environmental impact statement for DesertXpress high-speed rail project between Las Vegas and California, March 25, 2011.

Reader poll

Sun archives

- DesertXpress high-speed rail project rolls forward (3-25-2011)

- DesertXpress rail project going after tax dollars, after all (2-21-2011)

- DesertXpress top executive retires from high-speed rail project (12-17-2010)

- With new leaders, a revival of maglev high-speed rail? (11-25-2010)

- Harry Reid hopeful DesertXpress gets support from next governor (10-13-2010)

- Transportation secretary envisions nation connected by high-speed rail (10-13-2010)

- High-speed rail: Will it be worth the wait for Nevadans? (9-31-2010)

- DesertXpress likely further delayed by a federal agency (9-24-2010)

- Work on high-speed rail set to begin this year (3-25-2010)

- $45 million for maglev shifted to airport road project (3-17-2010)

- Backers of maglev train say Chinese bank prepared to fund project (2-3-2010)

- Maglev train backers woo contractors with promise of jobs (1-22-2010)

- DesertXpress prepared to build; maglev, monorail extension on hold (1-15-2010)

WASHINGTON — The future of a national high-speed rail system hangs in the balance of the budget.

As a down payment on a renaissance of American rail, President Barack Obama wants $53 billion over the next six years — a figure some criticize as too much, and others as too little by about an order of magnitude.

But even if lawmakers can steer their way through the dollars, there’s another potential tripping point in the track around the bend: Is Washington ready to regulate this sort of rollout?

It’s an issue that will affect Southern Nevada’s high-speed rail proposals.

The central federal authority for all rail-related matters is a tiny wing of the Transportation Department: Federal Railroad Administration. The administration is just slightly older than Amtrak, a name most Americans associate with passenger rail, and for good reason: Amtrak has been in charge of all passenger rail, by congressional order, for the past four decades.

The Railroad Administration has remained involved largely as a regulatory agency that focuses more on freight than passenger service.

But that division of authority started to change in the past few years, since administration officials began setting aside stimulus funds for high-speed rail — and entrusting the Railroad Administration to parse out the money, which, if the Obama administration gets its figure, will grow from an $8 billion initiative to a $53 billion portfolio, putting pressure on the 1,000-person shop to expand.

“This is uncharted territory for sure,” said Robert Puentes, a transportation expert with the Brookings Institution. “There are bound to be hiccups along the way.”

Although the Railroad Administration is taking on a new role, it’s not acting alone, Puentes notes: “There seems to be a more collaborative approach” in the Transportation Department,” he said, one that involves the president and the secretary lending the weight of their offices to high-speed rail promotion.

But Washington’s involvement so far has been limited to drumming up excitement and handing out funding to states to amp up their local rail; even the administration admits it’s just scratched the surface of what’s to be a 25-year national plan.

Officials envision a system built from the ground up, in terms of tracks, contracts, engineering and connecting a variety of public, private and foreign-funded rail projects.

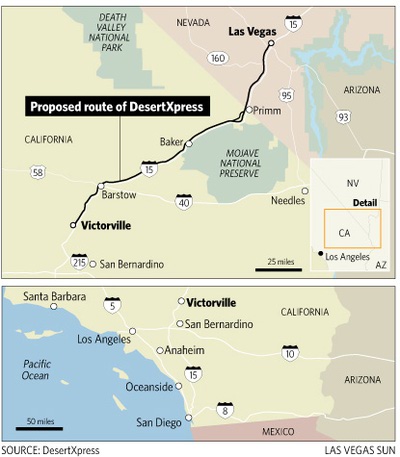

That gives Las Vegas an important stake in the federal government’s actions: Although local flagship rail venture DesertXpress hasn’t sought a single federal dollar to date, it is dependent on high-speed rail taking off in other places — such as California — if people are going to have a reason to ride the rails.

Backers of high-speed rail give the Railroad Administration’s work thus far their seal of approval.

“I think that the Federal Rail Administration, and particularly the staff that they have, have done a really great job of trying to get this money sent out,” said Tom Skancke, director of the Western High Speed Rail Alliance. “This is a new era for (the Railroad Administration), a new opportunity for them to get into the passenger rail business, and I happen to think that this is a great place for it to start.”

But some critics say the government is proceeding in too haphazard a manner to inspire confidence.

“It seems as though the executive branch really lacks the structure to execute this type of a huge infrastructure project well,” said transportation expert Richard Geddes, a professor at Cornell University, who pointed out that the Railroad Administration recently admitted it doesn’t do cost-benefit analyses of the programs it agrees to fund before awarding contracts.

“That’s a shocking revelation. The administration has not sat down and said ‘OK, let’s assess, as objectively as we can,’” he said. “They’re spending public taxpayer money and they should be very careful about ensuring that those moneys are spent not because it’s politically expedient to spend them in certain places, but because social cost/social benefits indicate they should be spent.”

At this juncture, the administration isn’t investing in high-speed rail exclusively. In fact, California was one of only two projects nationwide to receive initial federal grant funding under the stimulus for a high-speed rail project. Most of the rail money actually went to pay for incremental advances in train speed not quite enough to be called “high-speed.”

“They’re making a lot of incremental improvements that have to be made,” said Steve Kulm, a spokesman for Amtrak. “The route between Chicago and St. Louis, we can increase from 90 mph to 110 mph — increasing speeds is going to provide a benefit. And how do you improve rail traffic? Fix congestion in Chicago.”

All of that is far less glamorous than the dream of bullet trains flying across the tracks clocking speeds closer to 220 mph. But both Amtrak officials and Republicans in Congress seem to be downplaying at least the near-term expectations on that front; both will argue that the Boston-New York-Washington corridor is the only place where such a model truly has the potential to be cost-effective. And maybe California.

That’s not to say they’re both approaching that conclusion from the same angle. For Amtrak, it’s a question of how much money it has to work with; and although Amtrak has posted record revenue and ridership this year, it’s still dependent on the federal government, especially for capital projects: 90 percent of revenue for nonoperating initiatives come from tax dollars that Congress has to authorize.

On that front, Republicans just aren’t willing to spend what transportation-minded Democrats were in years past, when they controlled the House. The days of half-trillion-dollar surface transportation proposals are all in the past under current House Transportation Chairman John Mica of Florida — a state that rescinded its request for federal high-speed rail funding, sending it back to the Transportation Department this year.

Mica is writing a surface transportation reauthorization bill that he plans to move before the fiscal year is out. It will include a section on high-speed rail investment, but not likely of the sort Obama wants to see.

That’s potentially a blow to the high-speed rail revolution, which backers have tried to stress needs investment on the sort of magnitude as Dwight Eisenhower’s Interstate investment program.

“The interstate system is the backbone of what has made America the No. 1 economy in the world,” Skancke said. “The only proven formula of job creation funding in this country is transportation and infrastructure investment.

“And I happen to think that there needs to be a strong federal role in transportation, as it relates to regulation, safety, right-of-way management, and a certain amount of oversight,” Skancke said.

He pointed out that having an interstate oversight agency is what keeps states — which own the interstate routes in their boundaries — cooperating to keep the system working across borders.

“You can’t allow 70 different systems in this country and none of them connect; you’ve got to have a regulation for some type of interoperability,” he said.

But there’s a difference between interstate investment and high-speed rail — not the least of which is that the interstate was, and is, largely paid for by gas taxes. Lawmakers have shot down proposals to divert some of those taxes toward rail, or to direct a carbon tax toward a new rollout of rail.

Still, some advocates say reducing funding — or dealing with a slightly unwieldy Railroad Administration — may not be nails in the coffin of high-speed rail, arguing it was never supposed to be a fully federal initiative.

“There is a balancing act going on, moving up and down the federalist scale, of where the federal government should engage, and where they should get out of the way,” Puentes said, highlighting Intermountain West cities such as Las Vegas, Phoenix, Denver and Salt Lake City, which are raising revenue to bankroll surface transportation projects, both in traditional and innovative areas.

“It’s a self-help approach that they want recognition for from the federal government,” he said. “We’re starting to see a flipping of the financing pyramid, because those days of federal government funding everything are largely over, partly because of the economic crisis we’re facing.”

If more private companies do jump in the ring — and, experts point out, there been some interest from European and Asian countries more advanced in the development of high-speed rail — that would almost by definition create a more jumbled network of crossed rail signals for the federal government to regulate, because it would create competition for Amtrak’s long-standing monopoly on passenger rail.

But that’s not nearly as confusing, or as unprecedented, experts say, as it may seem — if you just look at what’s been running on a parallel track.

“A lot of people don’t realize that the vast majority of train tracks in this country are owned by private rail companies,” Geddes said. “Amtrak pays those freight rails for use of those lines; that was the deal back in 1970. But you could have a competing private company also pay for the use of those tracks, and that’s good for consumers.”

It’s not yet entirely clear where high-speed rail cars would use existing freight tracks — a sharing arrangement that brings up a whole host of right-of-way problems — and that’s certainly not what’s being envisioned for Las Vegas, where the projected $5 billion DesertXpress project is dependent on a new system of rails.

But that’s a private initiative until completion, and depending on how things progress in California, the federal government may not have to weigh in.

“They have to cooperate across state lines. That could be the federal government, but it doesn’t have to be,” Geddes said. “If you needed to coordinate between California and Nevada, the two governors could just talk to each other and hash this out. It’s not clear that you need some sort of entity in Washington.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy