More than 300 inmates at High Desert State Prison in Indian Springs receive adult education and vocational training from the Clark County School District through a partnership with the Nevada Department of Corrections. First-year Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones took a tour of the classroom facilities at the prison, about 40 miles northwest of Las Vegas, on Feb. 24, 2012.

Saturday, March 3, 2012 | 2 a.m.

The black Lincoln Navigator cruises northbound along U.S. 95 on a straight course to prison.

Inside the SUV is Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones — coffee cup in hand — watching the black expanse of asphalt unfold before him as his special assistant, Ken Turner, commands the wheel.

It’s early on a recent Friday morning, and Jones is running on four hours of sleep. Just a day earlier, he was traversing the Las Vegas Valley, heralding the School District’s new school ranking system.

A few hours later, Jones is back on the job, working to turn around one of the worst performing school districts in the nation. The odds are stacked against him, the statistics staggering.

The former Colorado education commissioner inherited a district where 61 percent of schools are deemed “failing” by the federal government and one whose high schools’ average graduation rate is 44 percent.

It doesn’t help that Las Vegas has some of the highest unemployment, foreclosure and bankruptcy rates in a nation facing the worst recession in more than 50 years. Jones knows the economic future of his beleaguered city of 2 million inhabitants hangs in the balance of his work in education.

Jones turns to Deputy Superintendent Pedro Martinez and Assistant Superintendent Bradley Waldron sitting in the back seat. “Tell me more about where we’re going today,” he says.

The focus today won’t be on the district’s Five Star students, they tell him, but on Clark County’s most troubled students: Some 300 inmates at the High Desert Correctional Center in Indian Springs. Jones is taking his first tour of a Nevada school behind bars.

For the past six years, the School District — in cooperation with the Nevada Department of Corrections — has operated a school for adult education and vocational training at the medium-security prison in the northwest valley.

The district provides the teachers and supplies. The corrections department supplies the classrooms and security. It’s all funded through the bulk of a $17 million state allocation to educate incarcerated youths and adults.

“They’re still our students,” Martinez tells Jones. “These are individuals who fell through the cracks. If we don’t serve them here, the ramifications are huge for taxpayers. If we can educate them, it’s better for our community.”

•••

More than 3,000 male inmates are incarcerated at High Desert, located in the middle of the desert some 40 miles northwest of Las Vegas. Most are there for lesser crimes, such as burglary, but the prison also serves as a temporary housing facility for death-row inmates, says Waldron, a former principal at a juvenile detention center.

More than 300 inmates at High Desert State Prison in Indian Springs receive adult education and vocational training from the Clark County School District through a partnership with the Nevada Department of Corrections. First-year Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones took a tour of the classroom facilities at the prison, about 40 miles northwest of Las Vegas, on Feb. 24, 2012.

Many of the inmates are high school dropouts, Waldron says.

Forty years ago, such dropouts could have landed a job in the ample manufacturing sector in positions that didn’t require a college education or even a high school diploma. But times have changed. Thousands of blue-collar jobs have been outsourced to foreign countries with lower wages and more lax regulations.

In the modern, global economy, high school dropouts are the ones left behind, working aimlessly in menial jobs or relying on welfare. Some ultimately take to a life of crime. In Nevada, many of them end up at High Desert. Earlier in the week, the prison admitted a 13-year-old gang member who killed someone in a burglary gone horribly wrong, Jones learns.

That stark fact weighs heavily on Jones, who understands that failing to properly educate students could lead to devastating outcomes, a costly proposition for Nevada.

Crime has its societal repercussions, but there is also a high cost to incarceration, an all-too-common phenomenon in America. Research shows it’s ultimately less expensive to send a student through private school for 12 years than it is to incarcerate that person for the same amount of time.

As the SUV veers off the highway into the prison parking lot, Jones eyes the vast desert landscape surrounding the concrete watchtowers, razor wire and tall metal fences. The group leaves behind their cellphones, wallets, ties and belongings, locked up in the SUV, taking with them only their identification.

Principal Bob Tartar, formerly of Rancho and Foothill high schools, greets them. He ushers Jones into the waiting room, where he meets Greg Cox, the state corrections director, and Dwight Neven, High Desert warden.

Jones and Neven shake hands.

“We need to make sure the right Dwight stays here,” Jones jokes.

They share a hearty laugh as they pass through a metal detector and several metal-barred doors and gates.

The group will be touring two parts of the school — adult education and vocational classes — Neven tells Jones as he leads the group down a hallway of classrooms. A green uniform-garbed guard accompanies them, his thick black-booted footsteps echoing off the concrete walls. Metal doors clang nearby.

Jones ventures into several rooms: English, math, history, science, computer training, even jazz band. The desks, chairs, textbooks, calculators, posters, teachers and projectors all belie the fact that this “classroom” is in fact inside a prison.

High Desert State Prison Warden Dwight Neven gives a tour of his facilities to Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones and Deputy Superintendent of Instruction Pedro Martinez on Friday, Feb. 24, 2012. More than 300 inmates at High Desert State Prison in Indian Springs receive adult education and vocational training from the Clark County School District through a partnership with the Nevada Department of Corrections. First-year Clark County Schools Superintendent Dwight Jones took a tour of the classroom facilities at the prison, about 40 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

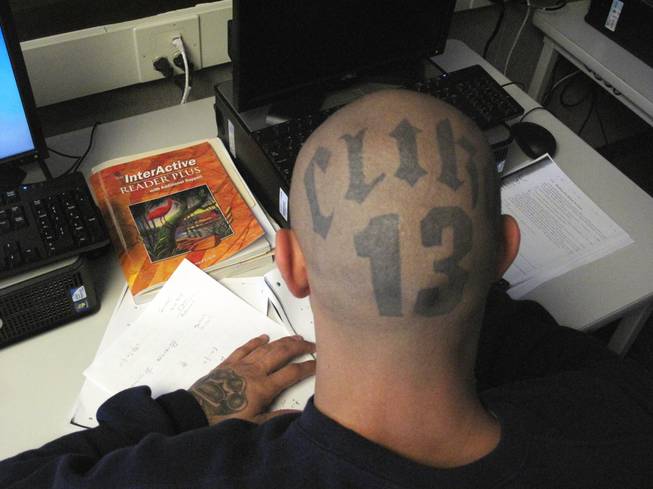

That is, until one notices the students, wearing prison-issued blue denim outfits and white sneakers. There are other signs, too: security cameras that monitor every move, panic buzzers and radios. Large windows appear on all classrooms and portables so guards can better monitor what’s happening inside.

There have been no incidents of violence against the 25 male and female teachers in the prison school, Neven says. In fact, these classrooms are the safest areas of the prison, he said.

At High Desert, inmates ages 18 to 25 must earn the “privilege” of their second chance at education, Neven said. Good behavior is rewarded with a low-security level clearance, which allows inmates to attend school, he said.

“This is all for their benefit, so they tend to fall into line,” Neven says. “They realize what they are learning is way better than sitting around doing nothing.

“Education, it has an impact on the yard,. Something sinks in: ‘I can do something with my time, or I can do time.’”

•••

The curriculum at the prison school is focused on one goal: earning either a high school diploma or the General Educational Development certificate, more commonly known as the GED. These diplomas allow inmates to qualify for $40-per-month prison jobs, such as converting high school textbooks into Braille to be used by blind students in Las Vegas.

“That’s a real good incentive (to get an education),” Jones remarks, noting if there were a way to convince people at a young age what a privilege it is to get an education, the chances of landing in prison later in life are drastically cut.

Tartar knows full well the power of the high school diploma and GED. Many of his students have gaps in their education, some with first-grade reading levels. Some adult inmates have limited computer skills, which in this day and age, rules them out of most jobs.

Some inmates are among the first in their families to become educated, changing the expectations of brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, he says.

Tartar has seen hardened criminals, gang tattoos and all, break down and cry during the prison’s school graduation. Earning that GED or high school diploma means so much to these inmates, Tartar says.

“It’s significant, because they’re coming in with nothing,” he says. “There are so many misconceptions about prison and my school. I tell people it’s something between ‘Shawshank Redemption’ and Boys Town.”

Martinez, who held a similar education role with the Washoe County School District, has worked with a number of prison schools near Reno. He also sees the redemptive role education plays in rehabilitating inmates.

Too often, inmates turned to crime at a young age because they had a bad experience with school, Martinez says. They weren’t engaged enough, or negative influences interrupted their studies. Falling further and further behind, these students often drop out, and some end up in gangs and a life of crime, he says.

“The fact is that when students have a bad experience in elementary school, they’re marked for life,” he says. “When you have someone who never had that confidence to realize (getting a diploma) is possible, it changes them. This program is about restoring their confidence.”

Turner, a School District consultant, nods in agreement: “It changes their mindset about what they want to do with their future.”

•••

Tartar steers the tour to the Youthful Offender program, which trains inmates for vocations such as the culinary arts, auto mechanics, construction, and heating and air conditioning.

“Our goal is to get them a job (once they get out of prison),” Tartar explains. “That impact is really dramatic out here.”

The majority of inmates will get out in a few years, he adds. Many may return to Las Vegas, where an improved job prospect makes all the difference in whether inmates return to a life of crime or stay on the straight and narrow.

To get into the Youthful Offender program, inmates need a GED or high school diploma, Tartar says. Again, the motivation to get an education is reinforced, especially because many inmates realize a proper vocation could help them land legitimate jobs after their prison term ends.

A culinary student at the High Desert State Prison prepares a chocolate dessert on Friday, Feb. 24, 2012. More than 300 inmates at the Indian Springs prison receive adult education and vocational training from the Clark County School District through a partnership with the Nevada Department of Corrections.

Jones walks through a classroom where teacher Wendell Smith is helping a handful of students learn how to install a thermostat and HVAC system. The entire classroom in rigged with rows of heating and cooling units, all installed by inmates.

“Some of them are extremely talented young men,” Smith says. “They’re trying really hard to get out (of a life of crime).”

Jones shakes hands with Smith, as he does with many teachers on his school visits.

“It’s an honor to meet you,” he says. “I want to thank you for what you’re doing. You’re helping them lead a different path in life.”

Jones and his team walk through the auto shop, where students are learning how to change brakes on a car donated by the School District. Outside of the garage, a team of construction and metal-working students is building parts for a gigantic new observation wheel at Mandalay Bay.

(Here, too, security is tight. Tools are constantly monitored and inventoried, and inmates must go through a metal detector before they are allowed back into their housing quarters, Neven says.)

Jones seems impressed with the prison school as they make their way back out.

“They get it,” he says. “If (inmates) are learning how to contribute back to society, it’s a pretty great investment.”

•••

Amid the recession however, funding for the adult education and vocational programs at prisons across the state has been slashed. Clark County received a 28 percent budget cut, which has meant fewer resources to help inmates get back on their feet.

That troubles Jones. About 75 percent of inmates who receive their GED, high school diploma or a vocational certificate never return to crime. That’s impressive, he says, especially considering the recidivism rate for inmates 18 to 20 years old is about 50 percent.

“If you’ve got those kinds of results, it’s amazing the state would cut funding from the program,” he says. “Sometimes people lose sight of the big picture. In tight budget times, you’ve got to see it and see the impact.”

Cox agrees: “Every penny spent is worth it. This is enhancing the public safety of our community.”

Despite the budget cuts, Jones would like to see some improvements made to his school behind bars.

As state proficiency tests and vocational certification become computerized, the School District and the Nevada corrections department are looking at ways to get inmates limited Internet access. Currently, state law prohibits online access in prison, which also complicates synchronizing data between the School District and High Desert.

The two groups may co-sponsor a legislative bill easing that rule, Jones says. That also would allow online classes in the prison, he adds.

More important, Jones hopes to ease the transition between prison and the outside, he said. Some inmates who are released from prison and did not finish their education usually enroll at Desert Rose Alternative High School, but Jones hopes to steer more students into other alternative programs.

Currently, the School District is piloting the Ombudsman program, which allows more than 300 students to attend two locations for credit retrieval classes — one at the v teaching center and the other at an alternative school on Maryland Parkway and Sahara Avenue.

Started in September, the program had seen success in Colorado, Martinez says. He and Jones would like to see the results — 85 percent of students catching up — replicated in southern Nevada. They believe inmates transitioning into private life would be good candidates for the program.

“This is an investment that pays high dividends,” Jones says. “If we’ve failed them on the front end, we’ve got to help them on the back end and pull them on a different path.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy