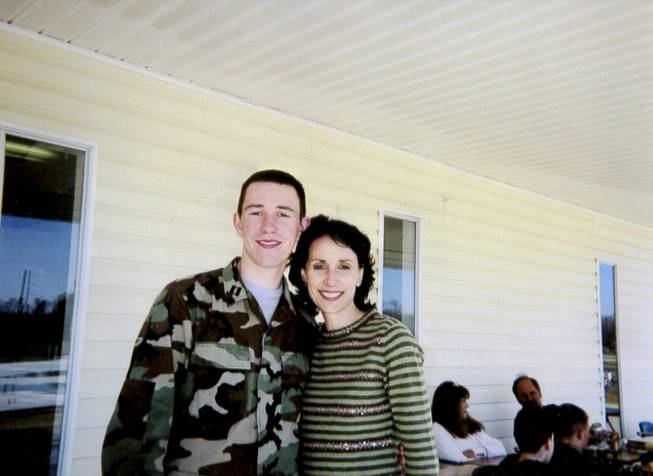

Courtesy Photo

Cathy Hill with her son Dillon circa Aug. 2005.

Wednesday, Aug. 7, 2013 | 2 a.m.

J. Patrick Coolican

Dillon Hill was 25, caught for the third time in just a few months shoplifting small items from a Wal-Mart. Once a bright and promising UNLV student, he was selling the stolen goods to buy heroin.

He was at the Clark County Detention Center awaiting trial and prosecutors said they would seek a 12- to 36-month prison term. Hill, coming off heroin, was deeply depressed and told his mother he was considering hurting himself, which she relayed to the jail.

Not long after, on Good Friday of this year, a fellow inmate found Hill unconscious and near death. Dillon Hill had taken a bed sheet into the shower room and attempted to take his own life. He would never wake up and died a few days later, on April 2.

A source familiar with jail operations, and the Hill case specifically, said the jail is generally a well-run operation staffed with competent professionals. But the source, who is not an inmate or former inmate, added that though the Hill case was an isolated incident, it was also a preventable debacle.

Dillon’s mother, Cathy Hill, hopes to keep this nightmare from afflicting other families.

She says her son’s case illustrates how prevalent the opiate problem is in Southern Nevada — up and down the socioeconomic ladder — while treatment options remain scarce.

A few years ago, the Las Vegas Sun analyzed Drug Enforcement Administration data and found Nevadans consume twice the national average of several prescription painkillers, which Dillon Hill began using before graduating to heroin.

The problem burdens a criminal justice system not always equipped to deal with what is both a criminal but also a public health issue.

Finally, Hill wonders how her son — a known heroin addict going through withdrawal and whose mental state was flashing red warning lights — could be allowed to take his own life with a bed sheet in a jail shower.

•••

Cathy Hill is a single mom who worked several jobs to support her children. She is a devout Christian and raised her children in the faith.

Dillon was a smart kid who attended Christian schools before graduating from Desert Rose High School. He is described by people who knew him as sweet and gentle. He loved snowboarding and cliff jumping at Lake Mead and hoped to be an engineer, enrolling at UNLV for at least one semester in 2006, according to the university, while working for a local landscaper.

At some point, he started using painkillers.

In December 2011, Hill says, “I just knew something was wrong — something seemed spiritually wrong.”

She tried repeatedly to reach out to him. Finally, he came home, emaciated and racked with addiction. He detoxed at home and at the urging of family enrolled in a drug treatment program in Dallas. After 30 days, he wanted to come home.

“I knew it wasn’t enough time,” says Hill, who began educating herself about addiction through Al-Anon and Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

Cathy begged him to stay beyond the 30 days and tried to persuade the treatment program to keep him there, but they replied, correctly, that his stay was entirely voluntarily.

He returned home and relapsed not long after.

In November 2012, his string of arrests began for shoplifting stuff like DVDs. Hill’s public defender, Carli Kierny, told me she believed Dillon had a lot of promise and was hoping he could enroll in Drug Court.

But Kierny said that after the third arrest, the District Attorney was seeking a lengthy term in the state prison, which is known as a much tougher environment than the jail.

What happened next is not completely clear.

I filed a public records request for all investigative materials of Hill’s death with Metro Police, which runs the jail. I received a one-page summary of his death with very little detail.

Later, a spokesman said the investigation into what happened would take another three months, and that Metro wouldn’t talk about it or release documents until after it was completed.

The source familiar with the jail operations said there were striking facets to the Hill case.

• When Hill was asked by a psychiatric nurse to rate his level of depression from one to 10, with 10 being most depressed, he gave himself a 9. Yet, there’s no indication of any further psychiatric exam.

• Hill was brought off the heroin detoxification protocol relatively quickly. The detoxification protocol would provide the inmate with drugs to ease the pain and insomnia of opiate withdrawal.

Cathy Hill says that after she alerted jail personnel that her son mentioned hurting himself, corrections officers checked on him.

Lindsay Hayes, a national expert in jail suicide, has written that “despite an inmate’s denial of suicidal (thoughts), their behavior, actions and/or history speak louder than their words.”

Hill was not placed on suicide watch, which would have entailed an isolation cell with frequent eyeball checks by officers and have made Hill’s manner of suicide — with a bed sheet in the shower — all but impossible.

Since Jan. 1, 2010, there have been four suicides in the Clark County Detention Center, a number too small to draw a clear statistical conclusion given the jail population and high rate of turnover.

Nationwide, suicide is the leading cause of death in local jails. The national jail suicide rate was 42 per 100,000 in 2010, which is more than three times the non-jail suicide rate. Also, outside its jails and prisons, Nevada has one of the highest suicide rates in the nation, which means our jail population is at high risk.

During a recent 2 ½-hour tour of the jail, I found it to be orderly, especially considering the nature of the population in the jail’s custodial care.

Here are some of the challenges in managing the county jail:

• About 3,500 inmates are housed at the main detention center in downtown Las Vegas, even though the ideal population would be 2,800. In 2011, the jail booked 78,000 inmates; in the main housing areas, there are 72 inmates per officer.

• According to a nurse practitioner on staff, about half the inmates are on some kind of psychotropic medication. Jail personnel estimate 80 percent or more of the inmates such as Dillon Hill arrive under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

• Last year there were 54 attacks by inmates on staff members, and hundreds more inmate-on-inmate attacks. Half of the attacks on staff come from inmates who suffer from psychiatric illness, according to Capt. Richard Suey, who has been at the jail for 22 years.

• The jail moves 500 inmates per day to and from the courthouse, serves 14,000 meals daily and distributes medication as needed.

In short, the Clark County Detention Center is a psychiatric facility, a detox center, a hospital, a pharmacy, a food preparation facility and a jail.

Suey said jail personnel are aware of their role as the region’s largest psychiatric facility. All new officers are required to get certification in the Crisis Intervention Team model, which is a nationally recognized approach to policing the mentally ill. Of 696 corrections officers, 360 are currently CIT certified.

Suey decried the lack of mental health services in Southern Nevada. In the absence of better treatment on the outside, the jail is a de facto psychiatric institution, he said.

“We had to get better,” Suey said. “We knew the state wasn’t going to do it. So we’re it.”

For Dillon Hill’s mother, this offers no comfort. At the very least, she would like to see the jail make the showers suicide-proof.

For her, though, the real prevention should begin much sooner. She is certain some doctors are overprescribing opiate-based pain medications, which creates a vast supply for habit-forming recreational use, especially among the young and curious. That supply, in turn, creates its own demand, as recreational use becomes addiction.

Hill is frustrated by the lack of drug treatment programs in Nevada, and with good reason. Nevada spends just one-tenth of 1 percent of its state budget on drug prevention, treatment and research, according to the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, far less than other states, despite widespread evidence of a worse-than-average substance abuse problem.

Hill also sees the criminal justice system as little more than a revolving door that fails to address the fundamental problem of addiction. She believes a rigorous, mandatory, 90-day treatment program after Dillon’s first arrest might have prevented the second and third.

Drug court, the strictly supervised alternative which is lauded by many of its graduates, currently has a waiting list of two to three months.

Jeff Iverson, a drug court graduate who runs sober living facilities, called substance abuse the region’s most serious public health problem.

“People are just in denial,” he said.

Sadly, we cannot count Cathy Hill among them.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy