Wednesday, Jan. 23, 2013 | 2 a.m.

Archives

Retired Metro Police Officer Raymond Berni won’t forget his proudest moments on the force during his 35 years of service patrolling the streets of Las Vegas.

There was the sentimental: doing a ride-along with his daughter, Candice, who extended the family’s deep law enforcement history by becoming an officer like her father, grandfather and great-grandfather.

And then there was the exhilarating: catching John Edward Bruce, a seven-time convicted felon, in the mid-1980s and recovering 97 illegal weapons, one of the biggest gun seizures in the department’s history.

“I’ll never forget that name,” Berni said.

It’s unlikely many will forget Berni’s name either. The longtime police officer retired in late December, and the city of Las Vegas issued a proclamation designating Dec. 27 as “Police Officer Raymond Berni Day.”

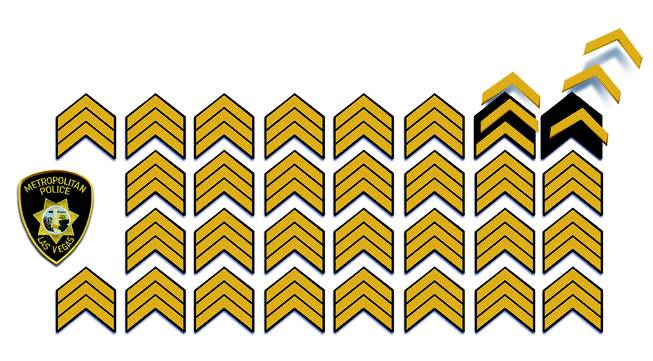

Berni joined dozens of Metro officers last year who decided to retire and turn in their badges. For Berni, who left as the most-senior rank-and-file officer on the force, the decision boiled down to economics and a sense of satisfaction.

“I loved being a police officer,” he said. “I’m not leaving because I’m angry or upset. I’m not burnt out. I’m leaving on my terms, and I’m leaving on top.”

A string of goodbyes

Berni’s departure meant another subtraction on a large whiteboard leaning against a wall in Deputy Chief Kevin McMahill’s office. As McMahill explained, the board is “a breakdown of the patrol division to the nth degree,” listing in black marker the number of captains, lieutenants, sergeants, supervisors and patrol officers working in each area command at any given time.

“Those numbers are just dropping so rapidly,” he said, pointing to the department’s determined minimum number of patrol officers: 1,095.

As of mid-January, the department was operating with 1,151 patrol officers — 56 away from that bottom number.

“A lot of it depends, but I would anticipate within the next three to four months, we’ll meet that threshold,” McMahill said.

Last year, 145 police and corrections officers of all ranks “separated” with the department for reasons such as retirement, resignation or termination, according to Metro data. That number excludes civilian employees and temporary workers who left.

It’s the highest number in six years, although only a slight increase compared with 2011, when 141 commissioned officers left the department. The number of officers who departed in 2010, however, just barely hit triple digits at 102, according to department data.

Those numbers don’t surprise Chris Collins, executive director of the Las Vegas Police Protective Association, the union representing nonsupervisory police and corrections officers. Collins said he seemed to be frequently awarding plaques to retiring union members.

“I remember doing four or five or 10 a year,” he said. “Now it seems like we’re doing one a week or two a week.”

Why remains an elusive question without a clear-cut answer. Department leaders cite a variety of reasons for the increase in departures: a core group reaching retirement age, less financial incentive to stay and the desire for a break from the daily stress of policing.

The department is operating under a $46 million deficit courtesy of the recession that crippled Southern Nevada’s economy. To help stem the gap, the department is seeking legislative approval this year for a quarter-cent sales tax increase.

Because of the economic downturn and its ripple effect on the budget, officers have not received a cost-of-living adjustment in nearly five years, Collins said.

“They realize, because of the economy, that their best years financially are behind them,” Collins said. “There’s no new money coming.”

And the past two years, specifically, haven’t been without controversy for the department. There was the battle over the coroner’s inquest, settled only recently; a flawed radio system; and scrutiny surrounding officer-involved shootings, which led to a Department of Justice report and recommendations.

“Does it provide a level of discomfort for a lot of our cops? You bet,” McMahill said. “Does it provide discomfort for me as a chief? You bet.”

Even so, McMahill said he was reluctant to attribute any of these events to a spike in retirements, especially since the department continues its focus on “admitting fault and doing something about it.”

“I just think you’re starting to see more and more people arriving at the age of retirement,” he said. “They have the ability to retire and they’re taking advantage of it.”

Collins offered another possible explanation: a study by the Los Angeles-based Consortium for Police Leadership in Equity that found poor morale among Metro officers.

“I think that’s what is pushing the officers out the door,” he said, blaming the economy for the morale dip. “It forces our administration to make decisions they would not have had to make.”

The domino effect

The department has not hired new officers in several years, aside from a class of 25 to provide for the opening of Terminal 3 at McCarran International Airport, Collins said.

Vacant positions created by retirements have gone unfilled and will remain that way, Sheriff Doug Gillespie recently told the Sun’s editorial board. That includes an assistant sheriff position vacated by Raymond Flynn, who retired Friday.

The scenario will continue to put a squeeze on that minimum patrol number on McMahill’s whiteboard, forcing difficult decisions about how to allocate officers.

McMahill said specialty squads, such as problem-solving units, face potential disbanding, with those officers returning to patrol.

“They’re an effective luxury, but they’re a luxury,” he said, describing such squads.

Reassigning detectives from certain divisions back to patrol could come later — a management decision McMahill said won’t “sit well with anybody.”

For the community, that would mean longer wait times for burglary and fraud investigations, if there are fewer detectives to handle cases, McMahill said.

The department recognizes its primary function is responding to 911 calls, hence the emphasis on maintaining an adequate number of patrol officers, McMahill said.

“Hopefully, we don’t get to a point in our manpower that something breaks,” he said. “That’s probably my No. 1 fear.”

In the meantime, McMahill said he was confident a batch of younger, dedicated officers — many who possess advanced degrees — would step up to fill voids left by their senior colleagues opting for retirement.

“We’re still attracting, developing and retaining the right people, and so I’m not really afraid of the brain drain as much as some people are,” he said. “I think we have some really good people.”

That doesn’t mean it won’t take time, though. Collins pointed to specialized detectives as an example of the learning curve.

“When they leave, (they’re) virtually impossible to replace,” Collins said. “It takes years of being a homicide detective to really say, ‘OK, I can do this on my own.’”

Life after Metro

On Thursday, Flynn sat in his nearly empty office and recalled the changes he has witnessed since joining Metro almost 33 years ago.

When he was hired in 1980, Metro employed just shy of 900 people, he said. Now the department has more than 5,000 employees — a growth spurt that paralleled the building boom in Las Vegas.

The father of four and grandfather of one doesn’t hesitate to declare his love for Las Vegas, now home to this native New Yorker.

“We got involved in the community, and what a great community,” he said. “I have no regrets raising a family here.”

He raised his family while working his way up through Metro, spending time in patrol, SWAT and the organized crime bureau, among others. His favorite assignment, however, was with the canine unit, where he worked with a sidekick named Danko, a German Shepard.

“I’ve had an incredible career,” he said. “I always wanted to make sure that when I left, I was going to leave happy, and I’m leaving very happy. I have no regrets.”

Flynn’s future plans read as diverse as his career: cooking and photography classes, perhaps teaching a criminal justice course and setting sail on an Alaskan cruise this summer. Above all, he’s looking forward to spending uninterrupted time with his family.

“Even when you’re not here, you have the distraction of the BlackBerry going off,” he said. “I won’t have those distractions now.”

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy