Sam Morris / Las Vegas Sun

Mountain Pointe wide receiver Jalen Brown is brought down by Bishop Gorman defenders during their Sollenberger Classic game at Bishop Gorman Friday, Aug. 13, 2013.

Sunday, Feb. 9, 2014 | 2:01 a.m.

Concussions are the topic du jour these days in the NFL and NHL.

Despite the concerns, there's no question athletics can, and do, benefit young people. Sports can teach children confidence, teamwork and discipline, keep them healthy, create family memories and help establish an active lifestyle into adulthood.

But make no mistake: youth sports is a high-stakes, big business.

An estimated 45 million children ages 6 to 18 play organized sports in the United States, with their parents spending more than $5 billion a year trying to groom their kids into the next LeBron James or Serena Williams.

And there's no end in sight. Experts foresee the industry growing by at least $250 million a year.

Doting moms and dads happily shell out big bucks for equipment, uniforms, team dues, sports camps, private lessons, practice space, travel expenses and medical costs.

Kevin and Kim Atchison spend at least $10,000 a year for their 11-year-old, Erik, to play hockey. He plays for a Las Vegas travel club and roller hockey league, takes private lessons, attends summer hockey camps and flies around the country for elite ice hockey games.

"He has told me over and over since he was 6 years old, this is what he wants to do," Kevin Atchison said.

Still, it is highly unlikely most young athletes will ever play in college or a professional league. In fact, they're literally more likely to get struck by lightning than go pro.

Odds are, your kid won't be the Yankees' next pinch hitter

Most parents and young athletes dream of college scholarships and professional careers. But the odds of either happening are minuscule.

Just 3 percent of male high school basketball players make a National Collegiate Athletic Association team. Only 0.03 percent, or three in every 10,000, go pro.

The odds for football players are slightly better but not by much. Six percent of high school football players make the NCAA, while only 0.08 percent, or eight in every 10,000, play professionally.

"The goal many of us are focused on is not a realistic goal," said Mark Hyman, author of three books on youth sports.

No pain, no gain?

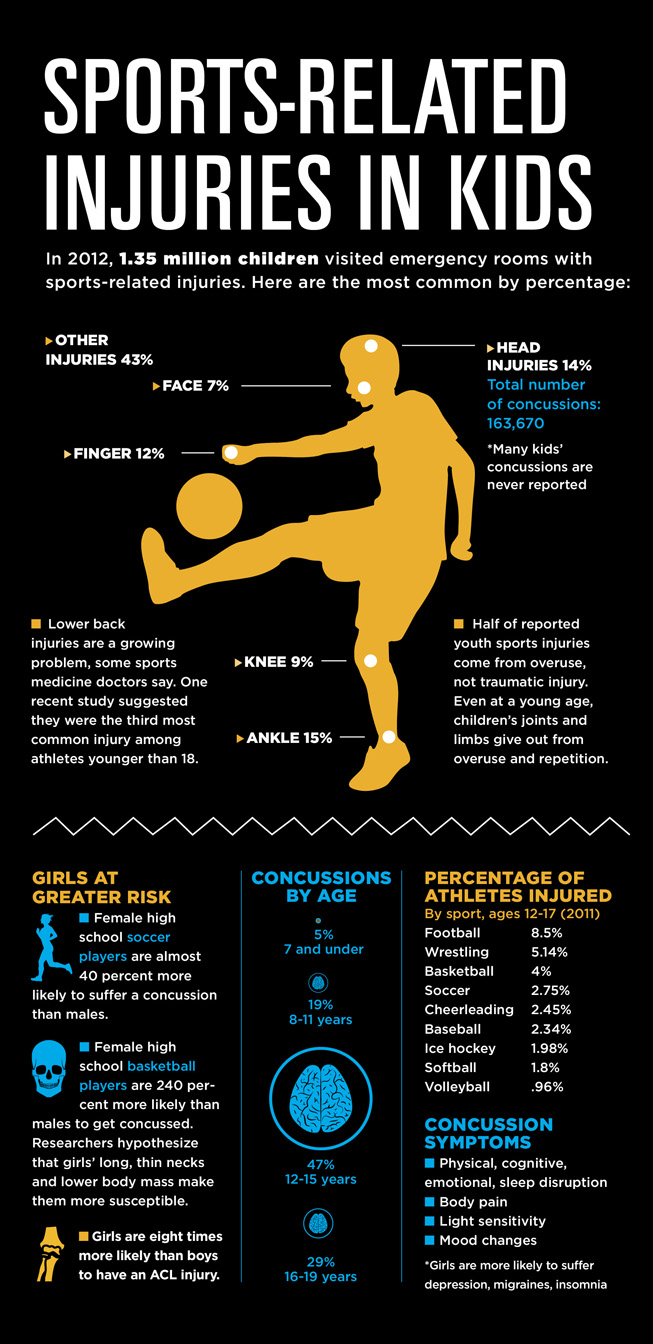

Almost 1.4 million children went to emergency rooms in 2012 because of sports-related injuries. The most common ailments were strains and sprains, but many were far more serious: fractures, cuts and concussions.

Concussions in youth sports rose 66 percent from 2001 to 2009, with high school athletes far more likely to suffer serious head injury than college players.

Young women are at particular risk. Researchers hypothesize that girls' long, thin necks and lower body mass make them more susceptible.

Almost a quarter-million children suffered concussions or other sports-related traumatic brain injuries in 2009, the most recent year for which data are available. Football, boys and girls ice hockey, lacrosse, wrestling, soccer and girls basketball were most dangerous, and children who suffered previous brain injuries were far more likely to suffer more-severe recurrences.

Most young athletes typically recover from a brain injury in a week or two, but 10 to 20 percent suffer symptoms that take weeks, months or years to abate. Some never heal completely. Athletes who return to sports before their brains have fully healed are at more risk for lasting, serious consequences.

The autopsied brains of former professional football players have shown evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which has been linked to clinical depression, suicide, dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

And helmets seem to offer little protection. A recent report by the Committee of Sports-Related Concussions in Youth, affiliated with the nonprofit National Academy of Sciences, found limited evidence that helmets reduce the risk of concussion.

Still, half of reported youth sports injuries come from overuse, not traumatic injury. Even at a young age, children's joints and limbs give out from overuse and repetition.

Dan Kazmierski, president of Green Valley Little League, regularly sees kids who are dominant pitchers at age 10 or 12 and by 14 or 15, "they can't raise their arm above their shoulder."

Worse, many kids hesitate to report injuries because they feel that the game and their team are more important than their health. They play through concussions, sprains and chronic pain to avoid letting down their teammates, schools, coaches and parents.

Some teams and leagues have instituted measures to try to reduce player injuries – adopting "hit counts," for example, to limit the number of collisions an athlete can experience in a practice or game – but no data exist to show whether such approaches are effective.

A Massachusetts brain doctor also has started a campaign to ban heading, or using your forehead to hit the ball, in soccer for girls under the age of 14, but his proposal has encountered much resistance. One of the most vocal critics is Brandi Chastain, the Olympian who helped the United States win a World Cup. She maintains heading is an important and "beautiful" part of soccer and is perfectly safe if done correctly.

Comprehensive statistics on youth sports injuries in Nevada are hard to come by, as they're not compiled by state agencies or the Nevada Interscholastic Activities Association. However, the Center for Health Information Analysis at UNLV tracks some youth sports injuries — those that result in a hospital visit, as opposed to merely an examination by a private health care provider such as a physician or trainer. The numbers on injuries that led to hospital visits in Nevada are as follows: basketball 874, soccer 618, baseball 405, swimming 159, cheerleading 127, football 64, ice hockey 23.

Source: Safe Kids Worldwide; Loyola Medicine

Parents gone wild

Pee Wee football parents fight in a Texas parking lot after a coach shoves a referee. A Colorado dad sparks a brawl after confronting an opposing coach at his son's baseball game. A Massachusetts father gets sent to prison for eight years after beating another man to death at their sons' hockey practice.

Youth sports are supposed to be fun, and for kids, but too often, parents steal the show.

To prevent outbursts, many youth leagues in Las Vegas and elsewhere require parents to sign codes of conduct which, if violated, can ban parents from games and suspend children from playing. Twenty-one states have laws addressing assaults on officials.

The Heat Football Club, a soccer team in Henderson, makes parents sign a 16-point memo outlining acceptable behavior.

"I will not harass, yell at or agitate a referee before, during or after a game."

"I will not badger, ridicule or taunt players from my team or the opposing team. They are ALL children and they ALL have feelings."

"I will not interfere with a coach during a game or practice. If a problem arises, I will abide by the 24-hour 'cooling-off' period before contacting the coach in any way (email, phone or in person.)"

Goodbye, free time

The Vegas Encore Volleyball Club includes an elite group of high school athletes. Many of the girls have played in the Junior Olympics and are set to play volleyball in college.

But being that good comes at a price. Volleyball is the main focus of their lives.

Vegas Encore members practice four days a week, work out twice a week with strength and conditioning trainers and receive "mental toughness training" twice a week. The squad also travels 16 times a year, including for several national tournaments. Registration costs $3,600 a season

"You can't have a social life," club Director Rodney McKimmey said. "You've got to make a decision."

McKimmey's athletes are on the court year-round. They play for their high school teams, and when that season ends in November, they join Vegas Encore, which runs until July. Then they enroll in summer camps.

"They love it," McKimmey said. "It's a commitment."

Where to play

Like most metropolitan areas, the valley has no shortage of youth sports. Not into football or baseball? No worries. Las Vegas offers curling, fencing and horseback riding clubs, too.

- Green Valley Elite (baseball)

- Spring Valley Little League (baseball)

- Vegas Elite Basketball Club

- Nevada Jr. Storm (hockey)

- Las Vegas Junior Wranglers (hockey)

- Vegas Encore Volleyball Club

- Nevada Youth Football League

- Southern Nevada Pop Warner Football Conference

- Las Vegas Swim Club

- Boulder City Henderson Heatwave Swim Team

- Heat Football Club (soccer)

- First Tee of Southern Nevada (golf)

- Fencing Academy of Nevada

- Las Vegas Curling

- Dressage of Las Vegas at Cooper Ranch (equestrian)

- Talisman Farm (equestrian)

Trophies for all

First place? Here's your trophy!

Fifth place? Take your medal!

Last place? Lift that trophy high!

Youth sports leagues throughout the country have taken a new approach to competition, handing out "participation trophies" to players simply for showing up.

Proponents say it emphasizes fun, effort and teamwork. Opponents argue that it coddles kids, instills in them a sense of entitlement and fails to equip them with the tools they'll eventually need when they do face disappointment.

On a larger scale, critics worry that the phenomenon is creating a lazy generation of ego-inflated people who don't understand the value of hard work and expect to be patted on the head not for doing anything special but simply for existing.

Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck found that while children respond positively to praise, if they are lauded for insignificant things, they quickly catch on, lose trust in the praise and collapse at the first sign of difficulty. Worse, they stop taking risks for fear of failure.

Parents and coaches are catching on, too, and spearheading a trophy backlash. Moms and dads increasingly are steering clear of trophy leagues, and sports officials are doing away with trophies for all.

In Texas, the Keller Youth Association football league garnered national attention last fall when its board of directors decided to stop giving trophies to every player.

"The biggest thing is we want to teach these kids (that) everything in life isn't going to be given to them," a league official said. "Your boss when you go to work isn't going to give you a trophy just because you showed up on time."

Trophy and award sales are an estimated $3 billion-a-year industry in the United States and Canada. Some leagues spend more than a tenth of their budget on medals and awards.

And while awards certainly can motivate kids, nonstop recognition doesn't inspire children to succeed.

"If children know they will automatically get an award, what is the impetus for improvement?" author Ashley Merryman wrote. "Why bother learning problem-solving skills, when there are never obstacles to begin with? This school year, let's fight for a kid's right to lose."

How are coaches screened?

• Leagues require coaches and other volunteers with direct access to players to undergo background checks conducted by a private company or local police department.

• Volunteers cannot have a history of assault, child molestation or other criminal incidents involving children.

• League administrators typically check references and call other league officials to ask about a potential coach's character. "Our volunteer coaches are interviewed and screened each season to ensure they are here for the kids and not their personal glory," the Southern Nevada Pop Warner Football Conference website says.

• Coaches can be suspended for threatening parents or other coaches, attacking referees or abusing players. Some infractions, such as assault, can send a coach to jail. Lesser offenses can result in league suspensions, with lifetime bans possible.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy