A July 9 vigil organized by local members of the Black Lives Matter movement honored black individuals from around the country who’ve been killed through police actions.

Monday, Oct. 3, 2016 | 2 a.m.

Before the world knew Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile, Terence Crutcher and Keith Scott for how their lives ended — police bullets or brute force — Las Vegas had grieved such deaths.

Trevon Cole, 21, died in the apartment he shared with his pregnant girlfriend.

Stanley Gibson, 43, died inside his white Cadillac.

An officer fired on Cole when he made a “furtive movement” during a mishandled narcotics raid in June 2010. Another shot Gibson, a Gulf War veteran whose wife said he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, in a bungled attempt to force him from his vehicle in December 2011.

Both men were unarmed and black.

Their troubling deaths stoked anger in the community and, in part, triggered a U.S. Department of Justice investigation into Metro Police’s use of deadly force. Despite considerable attention from local media, the incidents didn’t ignite the civil unrest that officer-involved shootings have in other cities.

Not that Las Vegas is immune to unrest. Riots engulfed the Westside in 1992 after the Rodney King verdict in Los Angeles, to the point of protesters firebombing, looting and beating up innocents dragged from their cars. In the aftermath, police pledged a higher level of openness to the Las Vegas community and called for everyone to work together, said Tod Story, executive director of the ACLU of Nevada.

It wasn’t a cure-all, Story said, but it did create a foundation of trust.

“I think that’s what has led to the calm that has existed here thus far and hopefully will continue,” he said.

Metro’s officer-involved shootings peaked in 2010, when police shot and killed seven people and wounded 18 others. The numbers largely have declined since then, a trend the department attributes to reforms enacted after the federal investigation. Among the changes: introducing body cameras and training officers to reduce racial bias and de-escalate tense situations.

Even so, some community members speak of lingering racial profiling and harassment, of particular fear for young people of color. Of Metro’s six officer-involved shootings this year, two of them fatal, half the suspects were black and half were Hispanic.

Claytee White, a historian who has studied the African-American experience in Las Vegas, explains the double standard this way: Society and, by extension, police, don’t flinch when a suit-clad white man drives a Mercedes. Put a black man behind the wheel and it’s a different story.

“They see someone who is out of place,” White said.

She sees only one way forward: education. And it goes both ways.

“If you don’t understand the history, we can’t fix it,” said White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries. “History is the vehicle that will help fix all the injustices.”

• • •

Robert Plummer

The stripes on Robert Plummer’s sleeves identify him as the station’s captain. Decades before he took over Metro’s Bolden Area Command, he had an encounter with a Las Vegas police officer that made him say, “I don’t want to be like that guy.”

Plummer, then 17, was at a park with friends, the clock ticking past curfew. Citations issued by the officer were warranted, he said, “but his interaction was not as professional as one would expect — very rude, very condescending, basically with a jerk type of mindset.”

Still, Plummer said, he didn’t feel targeted because of race.

With the complexion he inherited from his black father and white mother, 48-year-old Plummer said he has experienced racism, from being denied an apartment in Las Vegas to his family being refused service at a Colorado Denny’s. Asked to put the badge aside in commenting on perceived tensions between police and the black community, Plummer said: “As a black man, I see there are some injustices that go on around the country. However, I also see it from the standpoint that we have to be our own keepers. … It’s about making the right choice; it’s about accountability.”

After the Rodney King riots in Las Vegas, during which he was a rookie tasked with protecting people caught in the fray, Plummer said Metro “had some good leadership that saw we needed to build better relationships with the communities that were over-policed, if you will, but under-represented and didn’t have a voice or didn’t feel they had a voice.” He believes critical issues in some minority neighborhoods — drugs, gangs and a lack of resources and opportunities — are bigger than law enforcement.

Plummer doesn’t “buy into” the notion that cops systematically seek to harm black people, and, citing Chicago murder stats, he asks why he hasn’t seen outrage from Black Lives Matter activists over black-on-black crime.

But he also knows the power of a single negative interaction, and that anger "may be warranted." “Each individual has their own situation,” he said, adding that Metro supports the right to peacefully protest.

In morning briefings, the Metro captain has been sharing a mantra with his officers: Every person you come in contact with in the day, add value to their life. That might mean opening a coffee-shop door for someone, or treating a crime suspect with respect.

“Have a conversation rather than just saying, ‘I’m going to arrest you and take you to jail and that’s it.’ ... Guardian mindset versus a warrior mindset, although not sacrificing your safety for it,” Plummer said, “because we don’t hire (officers) to go out there and get killed because somebody thinks differently or hates the color of the uniform.”

• • •

Lou Collins

After a lone gunman ambushed Dallas police at a protest in early July, killing five, Lou Collins’ phone rang. It was Capt. Robert Plummer, head of Metro’s Bolden Area Command.

As director of the Pearson Community Center and MLK Senior Center in West Las Vegas, the valley’s historically black neighborhood, Collins has a good pulse on where residents stand on social issues, and Plummer knew it.

“He called and said, ‘Hey, what are they saying? I know emotions are high,’” Collins recalled.

“You gotta understand, cops are cops, so the perception is the same here in Las Vegas,” Collins told Plummer. “I appreciate you calling me because you’re being proactive.”

What that meant: Las Vegas was not immune to racial tension between police and members of the black community. The conversation, however, highlighted something that may not exist in other cities — an open dialogue between law enforcers and minority groups.

A decade ago, police leaders began partnering with community and faith-based organizations to improve relationships and curb crime in West Las Vegas. The effort relied on engagement, not harsh enforcement. Under the leadership of several area-command captains, the initiative kept growing as officers got to know residents through casual encounters or occasions like neighborhood barbecues.

“The response was incredible,” Collins said. “The community began to see law enforcement in a total different light.”

But racial profiling and harassment linger, Collins said, making many black residents wary of police interactions. Mothers worry their sons will be targeted; young men keep their eyes peeled for black-and-white cruisers.

“We’re talking about this every day, all day, at the dinner table, at the churches, at the hair salons,” Collins said, emphasizing the severity of the problem nationwide.

And he’s not basing that solely on secondhand observations. Collins said he experienced racial profiling a few months ago at the Doolittle Community Center parking lot after an event on a Friday night.

A city marshal pulled up and ordered Collins and a friend, also black, to stand with their hands against his vehicle because there had been reports of two men canvassing the building. They told the marshal they were community leaders, not criminals. The disrespect struck a chord with Collins, who has never been arrested. He demanded an apology in the days that followed and eventually got one.

“He profiled us, and that’s what I wanted him to understand,” Collins said. “He learned. It’s going to make him a better officer.”

Collins is an advocate of more education and engagement, believing progress can continue if both sides try to understand each other’s history and perspective. If any group can be an agent of change, he thinks it’s the younger generation. “The millennials are the answer,” he said. “I’m grateful for the way they think.”

• • •

Frenchiena Monroe

“If you want to see a change in the world, you have to be the change,” said Frenchiena Monroe as she styled a client’s hair inside Studio 702 one hot August day. “If you don’t want people running around killing others, why should you just because you have a badge?”

Monroe, 34, grew up a few blocks east of the salon in a plaza on North Martin Luther King Boulevard in West Las Vegas. She thinks the police — and residents in general — fear coming to this side of town because they equate poverty with violence. So in marketing itself, Las Vegas projects images of tidy, landscaped neighborhoods in Summerlin and Henderson, letting minority-majority areas fall to the wayside.

“It’s no different than anywhere else,” Monroe said, though she’s hopeful change could be on the horizon. She said she has seen slightly more communication between Westside residents and police in recent years, and while she believes harassment still exists — particularly targeting black pedestrians — officers have been respectful toward her. She’d be heartened to see even more interaction, with officers swinging by church gatherings or dance competitions — anything that might drive mutual respect and understanding.

“When I’m pulled over, I never say, ‘Oh, it’s because I’m black,’” Monroe said. “If I’m speeding, you’re doing your job.”

• • •

Officers responding to a car accident set off attendees of a North Las Vegas vigil in protest of police brutality.

The July 9 Black Lives Matter gathering had been peaceful. Children held candles, activists sounded off and a woman sang a poem beneath a statue of Martin Luther King. The call to action had come after officer-involved killings of black men in Minnesota and Louisiana, and lit candles formed “138” — the number of black people reportedly slain by U.S. police in 2016, as of that day.

About a dozen sign-holding demonstrators abandoned the speeches and crossed the street from east to west and west to east during red lights. Noise from the wreck on the other side of the intersection attracted onlookers, and protesters flowed into and stayed in the street. Traffic was stopped for about 45 minutes, and as the crowd swelled, taunts were hurled at Metro and North Las Vegas police. Vigil organizers on megaphones tried to turn things back to peace.

“Everything is coming to a halt,” one woman said.

“Stop being scared!” a man challenged, trying to rile the crowd.

People shouted “black power,” “hands up, don’t shoot” and “black lives matter,” along with obscenities. A black woman screamed at a white officer: “You have no idea!” Another shouted, “We’re tired of you killing our black men! You guys are murderers!”

“We’re just tired,” said demonstrator Jessica Brown, adding that she’s afraid to have a son given the number of black men killed recently in incidents involving police. She doesn’t condone violence but approved of demonstrators blocking the street.

Officers deflected the shouts with silence, and their numbers grew to include reinforcements with riot gear and horses. There was pushback when an officer got on a loudspeaker and threatened arrests if the street wasn’t cleared. Demonstrators eventually were flanked and pushed to the sidewalks.

The intersection emptied with no physical contact. Anger and insults contrasted with a few handshakes and smiles between officers and protestors. Three were arrested for minor infractions, no one was hurt, and the crowd dispersed.

• • •

James Seebock

Hours after the deadly shooting in Dallas, Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo stood surrounded by local officials and officers at Metro’s headquarters. He asked that the community resist knee-jerk reactions and let the process unfold.

“We are here to stand together as an example of what a community can do when it comes together,” Lombardo said.

Capt. James Seebock, who heads the department’s training bureau and helped beef up its Adopt-a-Cop program, said coming together to effect change demands proactive thinking. “The time to establish relationships isn’t in the middle of a riot; it’s to be done ahead of time, and that’s what Metro has done.”

Launched several years ago by police and faith-based leaders on Metro’s Multicultural Advisory Council, Adopt-a-Cop dispatches new officers to community centers in higher-crime areas to have personal interactions with residents. They go in plain clothes and then in uniform, hoping to break down negative associations.

In the wake of last year’s riots in Baltimore — sparked by the death of Freddie Gray from injuries sustained while in police custody — Seebock has overseen the expansion of Adopt-a-Cop to schools, LGBTQ centers, juvenile and adult jails and the homes of Las Vegans. Since January 2012, 265 officers have visited 83 locations and 12 families (47 families have volunteered to participate). And over a three-day period in August, 54 new hires visited 16 locations and seven families with the aim of listening to concerns and building bridges.

“Metro feels the way forward in the 21st century is community interaction, is establishing those relationships,” said Seebock, adding that community policing isn’t a substitute for enforcement — it’s an important ingredient that depends on across-the-board engagement. “Everyone has a personal responsibility to try to grow those relationships, get rid of those old habits, old ways, and continue to look forward.”

• • •

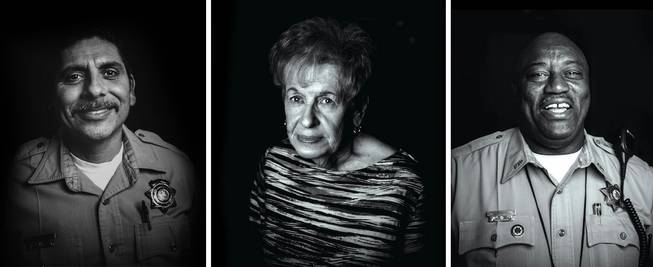

Sgt. Leo Aguilar (left) and Officer Vince Postell (far right) are training and evaluation coordinators for Metro's Adopt-a-Cop. Peggy Sanders is a volunteer for that program and for the department's headquarters, where she checks in visitors at the front desk.

Metro officers Justin Hee, Robert Wicks and Doug Calder canvassed Chinatown Plaza on Spring Mountain Road on a sunny August afternoon. One woman wanted to take a photo with them. For others they encountered, that level of comfort took work.

The uniformed officers met a lot of perplexed faces and downcast eyes as they walked the hub of Las Vegas’ Asian community. But once they made it clear they were there simply for face-to-face time, conversations started.

“When we’re trying to be social in uniform, it’s not what people expect, not like there’s a tent out front with Metro banners — ‘Hey, come meet cops’ — you know?” Calder said. Such interactions, added Hee, who grew up in this neighborhood, are a way to “make sure they know we’re also a part of the community and they don’t have to handle their problems on their own.”

In the central valley on a different day, Peggy Sanders, two of her neighbors and Metro officers John Ruiz and Blake Ferron sat around a box of doughnuts. The police weren’t investigating a call; they were hanging out. Social calls are key to Adopt-a-Cop, the officers said, as notions of police can be limited to distress calls or media portrayals.

“We’re not robots,” Ruiz said. “Not every cop is the same. ... All it takes is one officer to mess up and now they judge us all.”

Ruiz urges people to look beyond the badge. He said that whenever he meets residents he tells them to call him John — even during traffic stops. And while visiting homes and businesses for Adopt-a-Cop, he asks “what they want to see from us.”

Earlier in the day, Ruiz and Ferron had visited a Hispanic couple with five children. The kids were shy at first, but they ended up playing soccer with the pair. And the day before, the officers had spent time at a center for youths with behavioral issues.

“When we walked into the room it was really quiet. You see the look that they give you, of being afraid or angry,” Ruiz said. “And when we left, everybody was smiling — ‘Oh yeah, I know John and Blake; these are the good guys.’”

• • •

Ora Bland

In her 82 years, Ora Bland says she has never encountered racism. Even during her childhood in Pittsburg, Miss. “I don’t know if it was luck,” Bland said, recalling Sunday potlucks in Mississippi involving families of multiple races. “Color don’t mean anything as far as I’m concerned.”

She brought that mentality to West Las Vegas, where she has lived for over 60 years. For half of that time, Bland’s daughter worked in local law enforcement, including a stint with Metro Police.

Bland called the officers who patrol the old neighborhood her “friends,” adding that if it weren’t for them it wouldn’t be safe to walk down the street. She sees no problem with police in her community, even though some residents appear to hide when they see them.

“You can always find someone who is going to think negative. People are just like that,” Bland said. “I have a firm belief in this: If my child or some relatives of mine do something and Metro has to protect themselves, then I won’t make an angel out of that person. If they do something and Metro has to do what they have to do, I don’t blame them, I really don’t. Because I would want my daughter to protect herself.”

• • •

Bruce Soares

It was a Saturday in the 1980s, and Bruce Soares had driven his Mercedes-Benz to a convenience store after dropping off his son at a movie theater. As he reached for a newspaper, Soares said, he heard “don’t move” from a Metro officer pointing a gun at him.

Soares recalled that the officer ordered him to stand against the squad car and put him in handcuffs. He asked where Soares worked, and he answered that he was unemployed. The now-retired Postal Service employee said the officer couldn’t believe an unemployed black man was capable of owning a luxury vehicle. He did, however, believe Soares was capable of owning a gun, and that he’d ditched one at a nearby convenience store.

“The individual they were describing was Caucasian. Do you think I’m Caucasian?” the 68-year-old asked with a laugh.

He told this story inside a central valley police substation after a discussion about body cameras. It was part of 1st Tuesday, Metro’s monthly gathering aimed at bringing officers and residents together for meaningful conversations. Soares has ingrained himself in these talks for going on two years. He sees Metro moving in the right direction, noting the level of transparency that may result from officer-worn cameras.

“It’s unfortunate, but racism is alive,” Soares said. “I think people play political games and say, ‘We no longer profile.’”

He listed examples from his own life, whether it was trouble hailing cabs in other cities or watching people move away from him in elevators and stores, though such discomforts pale next to the fear he said “most, if not all” black parents feel regarding their children.

If Soares had a young son today, he would tell him: “This is not the time to be a comic, when police stop you. This is not the time to be a wiseguy.” He would tell him to answer questions politely while keeping his hands in view. “Being black in America is not an easy job,” Soares said.

He believes that the Justice Department’s 2012 report on Metro’s use of force and the subsequent reforms have led to improved relations between police and minorities. And he said anyone who feels disenfranchised should do something about it.

“It’s easy to complain,” he said. “You need to get involved.”

For more history, personal reflections and key statistics on Metro Police's use of force, click through the slides below.

-

West Las Vegas got the worst of local rioting over the Rodney King verdict in 1992.

Las Vegas Riots

Shaky images broadcast a police officer pushing Rodney King to the ground. Then the baton blows begin, two officers taking turns striking King’s limbs full-force. Another moves into the frame and kicks his head.

The now-iconic video from March 3, 1992, caused an uproar that spilled from Los Angeles to Las Vegas after a jury acquitted the four white officers facing charges. There had long been reports of police brutality, but no one believed them, Las Vegas retiree Bruce Soares said. The Rodney King video changed that. “I think some people in the overall community were surprised, but people who lived in areas where they weren’t respected weren’t surprised at all.”

Metro Capt. Robert Plummer was disgusted by the footage — “That’s not what I thought policing was about” — and recalled being a rookie officer working the night the riots reached Las Vegas. It began as a standard protest but rapidly devolved into a mob dragging white people from cars and beating them up, Plummer said. He’d been assigned to a team of officers that intercepted the furious demonstrators as they crossed the underpass near Bonanza Road and Main Street, throwing rocks and bottles.

He remembered it being tense for about six months. Initially, officers were tasked with “chaotic long days,” 12 hours on, 12 hours off. A police station was firebombed and looted. “There was constant gunfire and violence toward the police at that point,” he said.

Looking back, Plummer thinks Metro lost some ground in West Las Vegas by failing to reestablish key relationships when the dust settled. But the election of then-Clark County Sheriff Jerry Keller in 1995 put an emphasis on community and outreach in policing, a model followed in various ways by Keller successors Bill Young, Doug Gillespie and Joe Lombardo.

“Over time, we have become much better as a police organization,” Plummer said. “The way the police interact with the community, from when I started 25 years ago, is totally different.”

-

Community leaders and Metro Police Capt. Larry Burns gather in the parking lot of the Desert Gardens Condominiums complex near Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Bonanza Road Monday, Aug. 6, 2012. From left are: Alonso Jones, Pastor Willie Cherry, and Charles Webb.

Larry Burns

The bullet-riddled body of a man shot dead in Sherman Gardens lay outside for hours as investigators combed the public housing development for evidence and witnesses. Neighbors clammed up. No one wanted to be a snitch.

Metro Police Capt. Larry Burns and his community partners kept trying, quietly asking residents to share any information about the killing of 45-year-old Stacey Randolph that August night in 2013.

What happened the next day proved to Burns that police were doing something right in the neighborhood: His cellphone rang. The female caller said she could identify the gunman, but she feared for her family’s safety.

Back then, Burns headed up the Bolden Area Command near Martin Luther King and Lake Mead boulevards, serving some neighborhoods prone to crime. Residents, who could be wary of police, didn’t want to risk retaliation by helping them. But this woman trusted Burns, and it led to an arrest.

“The No. 1 rule of influence is to develop a relationship of trust,” Burns said. “If you are not doing that, I don’t care what your program is — nothing is going to change.”

When Burns took over the Bolden substation in early 2011, he bolstered what his predecessors started: partnering with community leaders and members to cut crime and strengthen ties in the historically black neighborhoods. He asked his officers to engage in two friendly encounters with residents each shift. Talk about sports, the weather, whatever. From there they began reading to schoolchildren, fixing up blighted properties and throwing holiday events, complete with a black Santa.

And then, at the request of his patrol crew, Burns eliminated the use of saturation teams.

“They are the ultimate zero-tolerance, hook-and-book guys,” Burns said. “I went to the saturation team lieutenant and said, ‘I don’t want your guys coming into Bolden anymore. If we need you, we’ll let you know.’ Well, that caused a great stir.”

Violent crime in Bolden fell during 2011, 2012 and 2013, while Burns led the area command. The reductions mirrored what was happening across the department, and nation, but when crime started rising again in 2013, Bolden was an outlier. It posted a 5.48 percent decrease, the largest within the department.

Burns retired in December 2013 to focus on his bid for sheriff, which he lost to the establishment-backed candidate, Joe Lombardo, by a 2-percent margin.

At the end of 2015, violent crime in Bolden had soared 15.72 percent over the prior year, reflecting a valleywide spike, though Burns believes the approach of law enforcement can defy trends. Did he take a softer one? Maybe. Was it effective? He’ll argue yes.

Burns insists he’s not a “bleeding liberal,” but he vehemently disagrees with the notion that everyone can overcome the disadvantaged circumstances he or she enters at birth. “That’s not reality,” he said. “I didn’t coddle anyone. I tried my hardest to walk just a moment in that guy’s shoes.”

Kane Nellis and Justin Neal

On a weekday afternoon at the Cambridge Recreation Center in the central valley, Kane Nellis and some friends were hanging out. Asked about issues of race in law enforcement, the young black man pulled dark-rimmed glasses from his pocket and said he carried them constantly.

“Cops see glasses — they don’t stop me,” he explained.

Nellis moved to Las Vegas several months ago from Florida to pursue a music career. Since then, he said, he has been stopped unnecessarily multiple times. Once, Nellis recalled, he was sitting on a picnic table when an officer approached and demanded his name. He chalks it up to racial profiling because he’s a black man living in an area perceived as a rougher neighborhood in Las Vegas. “I’m 30 years old,” he said. “I’m not running these streets.”

Not every officer behaves that way, he acknowledged, but Nellis thinks more need to practice the old adage: Treat others how you would want to be treated. As it stands, “we avoid them like a pack of dogs. That’s the best metaphor.”

Elsewhere in the rec center, Justin Neal was playing basketball with a friend. The senior at Valley High School said he hasn’t run into any overt stereotyping by police. He considers Las Vegas police “decent,” though he hasn’t interacted with them much, he said. The controversial officer-involved shootings and subsequent racial unrest happening in other cities, though, have him unsettled.

“I just hope it doesn’t happen out here.”

-

Metro Police officers meet with community members in Chinatown on an August afternoon.

Adopt-a-Cop

Pastor Willie Jacobs Jr. recently received a letter from Metro Police. It was a flier advertising the expanded Adopt-a-Cop program, an initiative that pleasantly surprised Jacobs, 76, who thinks some tension between police and residents can be soothed if officers take to heart their mission to “protect and serve."

He also thinks poor relations stem from a lack of understanding on both sides.

Many officers don’t grasp the struggles minority residents face, especially in poverty-stricken areas where drugs are plentiful but job opportunities are scarce, he said.

“They don’t understand the culture. They don’t understand the behavior. They don’t understand what that person has experienced in life,” said Jacobs, who leads the True Love Missionary Baptist Church on H Street. “I can understand why they act differently, because they don’t know.”

Jacobs said adults need to teach children and teens how to interact respectfully with law enforcers — even if unjustly stopped. “If you’re humble and you’re kind, they’ll let you go. They’ll give you some mercy. Don’t get an attitude with them.”

During Adopt-a-Cop's recent visit to her home, 52-year-old Maria Del Carmen Godinez smiled while showing her green Metro Citizen’s Police Academy diploma to officers Robert Thiele, 41, and Matthew Smith, 26. The interaction involved her family and friend Velvet Molina talking to the officers — sometimes in Spanish, since Smith speaks it — about everything from hometown memories to fears Hispanics face.

“I’m not scared of police,” said Godinez, crediting knowledge of the department’s inner workings gained through the academy. The same wasn’t true when her family lived in Mexico and then California, she said, citing corruption in their home country and rampant police profiling in the border state. “In California, you fear them. You feel the racism.”

“I’m sorry,” Smith said.

“Not here,” she replied.

“It’s a good place to be a cop,” said Smith, noting the support he has felt coming from the community.

Then Thiele asked what the department could do better.

“Everything is fine for me,” Molina said. “The people who need to change is us, as a community; we have to learn.” She described a traffic stop she witnessed, in which two young people not connected to the incident pulled out their phones and started recording. “You guys have your cameras taping everything, and people are getting into your business.”

Kendric and Candace Wilson

On the eastside of Las Vegas at the Hollywood Aquatic Center, Kendric and Candace Wilson watched their sons splash in a pool filled with children. Race didn't matter here. Laughter and chatter prevailed as kids and their parents escaped the blistering summer heat.

This is the type of environment the Wilsons hope their two young boys can continue enjoying. They want them to be leaders and surround themselves with positive influences. It’s the kind of aspiration most parents harbor, but the Wilsons know their kids might face more adversity because of their toffee-colored skin. Kendric has Jamaican heritage. Candace is white.

They grew up in Oak Grove (population 1,662) in northeastern Louisiana, where sweet-potato fields are plentiful and whites still outnumber blacks nearly 3 to 1. Dressed in hand-me-down clothes and living in a roach-infested house lacking water, Kendric knew he was viewed as inferior in their tiny town, but he graduated from high school and pursued technical training.

“We had no role models,” he said.

The couple’s relationship also defied social norms in Oak Grove, but Candace’s family largely accepted Kendric, she said.

They moved to Las Vegas for opportunity. He works as a porter at Caesars Palace, she as a cashier at Valley Hospital. But the city has also proved welcoming. People generally are more accepting of different ethnic backgrounds, they said, and the police haven’t bothered them. “It’s a little more open,” Kendric said. “They just look at us because she’s tall and I’m short.”

Even so, the Wilsons want their boys, ages 8 and 9, to know they may be judged differently by law enforcement, as police shootings across the nation have highlighted this year. They teach them to know right from wrong, treat everyone equally and avoid hanging with a bad crowd.

“They know the cops are the guys you don’t want to deal with,” Kendric said.

-

One of the many signs displayed as the Black Lives Matter organization holds another protest and march in downtown Las Vegas on Saturday, July 16, 2016.

Samuel Wright

Grim events happen with frightening frequency nowadays: Mass shootings at schools, nightclubs and malls. Fatal force used by police on unarmed black men. Lethal attacks against officers.

The tragedies demand preparedness beyond drills focused on emergency response, said Samuel Wright, a longtime Las Vegas resident and historian. They conjure deep emotions that, if not handled right, can tear people apart at a time when they most need to come together.

“When this happens here, what are you going to do?” he said, referring to local leaders. “I think the honest response is, ‘I don’t know what we are going to do, but let’s all sit down and start to work on it now.’ Anything else is going to be a bullsh*t answer.”

Wright believes lackluster mental health services and unchecked racism in police departments have contributed to violent episodes rattling cities across America, forcing community leaders to face uncomfortable realities. He said tensions have festered over many years as police unfairly targeted minority neighborhoods, leading to high incarceration rates for blacks and Hispanics.

“We have written rules and unwritten rules. One of the unwritten rules in America is that the primary job of the police is to keep the minority peoples — whatever color they are — under control,” the 69-year-old said.

That’s why Wright, who hasn’t had any negative experiences with police in Las Vegas, still thinks it’s important for minority parents to have meaningful conversations with their children about how they might be viewed. Of his 6-year-old grandson, he said: “His father and I will be having that conversation with him in the next couple of years.”

-

Metro Police close off Asbury Hill Avenue near Pecos Road after an officer-involved shooting Tuesday, Jan. 26, 2015.

Metro’s use of force

The Metro Police website offers detailed reports on officer-involved shootings going back to at least 2008. The six reported this year are on track to reflect the lowest incidence since then.

Following the Justice Department’s eight-month review of Metro’s use of deadly force, transparency became focal. Measures include commissioning officer-worn body cameras, holding public briefings soon after any shooting, releasing all information 72 hours afterward and showing any video footage during a lengthy press conference.

“Every Metro officer-involved shooting is closely investigated and reviewed by the Force Investigation Team, Critical Incident Review Team and the Use of Force Board,” Sheriff Joe Lombardo wrote in an August Las Vegas Sun column praising Metro’s reforms, expanding on one he wrote a year earlier. “This process not only allows us to determine whether the shooting was justified, it provides lessons learned in our tactics and responses to make changes that can reduce the use of deadly force in future situations.”

2016 Metro officer-involved shootings

Jan. 22: An officer investigating a disturbance call on the Strip near the Bellagio fountains encountered Kahleal Black, 21, who had his back turned. When Black spun around, he did so pointing a gun at the officer, who shot at him twice, missing. A child suffered a minor graze wound when a bullet ricocheted.

Jan. 26: Gilberto Gutierrez, 34, was accused of stealing two vehicles, the second while threatening the owner with a gun. Following a foot pursuit, he was spotted by a helicopter and shot. Officers had instructed him to drop a gun they said he was carrying and he did not obey. He survived the shooting.

Feb. 29: Juan Carlos Lopez-Aguilar, 43, had brandished what was later determined to be a fake gun as he walked through a south valley neighborhood. He did not obey an officer’s orders to drop the gun, and he was shot when he pretended to load a real bullet. He was wounded in the shoulder.

March 31: James Simpson, 31, was encountered in the street by officers responding to a call to Simpson’s mother’s house in the southwest valley, where he’d killed two of her neighbors. After negotiating and putting his gun down, Simpson picked it up again, ran and shot a round at officers. He was shot and later died.

April 11: Efren Trujillo Soriano, 22, after being robbed by a man he was talking to near the Stratosphere, went to retrieve a gun. He found the alleged robber and shot him. When officers were investigating, Trujillo Soriano returned to film them. A chase ensued once they realized he was a suspect. At an apartment complex, Trujillo Soriano turned and ran toward two officers, firing rounds. He was shot and killed.

May 6: Jamal Gwynn, 27, was accused of robbing a car at gunpoint. He was spotted by an officer after he wrecked that vehicle at a nearby west valley apartment complex. After a foot chase, Gwynn stole the officer’s patrol car and accelerated toward him while crashing through the complex’s gate, barely missing the officer, who shot him. He was arrested nearby after he lost control of the vehicle. He survived.

Metro’s approach to policing also emphasizes community engagement. Its substations host gatherings every first Tuesday of the month, where the public has an opportunity to meet officers and their superiors and even air their grievances. Adopt-a-Cop makes that interaction more personal, as does incident-specific outreach to neighborhoods impacted by crime. On Sept. 24, for example, officers respectively canvassed the northeast valley seeking clues in a year-old murder case and put together a block party at a west valley apartment complex where two men had been slain.

Connection is vital, and this spring the community was granted oversight on the selection of new officers. In the past, Metro candidates went before a hiring board of three officers. Now nine community members from different ethnic backgrounds are entitled to alternate through one of those seats and lend his or her voice.

White: Las Vegans (as of 2010 census): 45.9 percent; Metro officers (as of September): 1,935 or 73.3 percent; Metro officers involved in shootings (2011-2015): 76 percent; suspects shot by Metro officers (2011-2015): 39 percent

Hispanic: Las Vegans: 33.2 percent; Metro officers: 340 or 12.9 percent; Metro officers involved in shootings: 13 percent; suspects shot by Metro officers: 24 percent

Black: Las Vegans: 10.6 percent; Metro officers: 170 or 6.4 percent; Metro officers involved in shootings: 8 percent; suspects shot by Metro officers, 2011-2015: 24 percent

Asian: Las Vegans: 6.2 percent; Metro officers: 95 or 3.6 percent; Metro officers involved in shootings: 2 percent; suspects shot by Metro officers: 2 percent

Other: Las Vegans: 4.2 percent; Metro officers: 101 or 3.8 percent; Metro officers involved in shootings: 1 percent; suspects shot by Metro officers: 11 percent

Metro officer-involved shootings, 2010-2015

2010: 25, 7 fatal

2011: 17, 12 fatal

2012: 11, 4 fatal

2013: 13, 3 fatal

2014: 16, 8 fatal

2015: 16, 11 fatal

YTD 2016: 6, 2 fatal

Officer age/experience: 34-38/7-10 years

Suspect age/gender: 33-37 (youngest was 17; oldest was 58); 91 percent male

Suspect criminal history: 86 percent had criminal backgrounds; 57 percent had been convicted of a violent crime; 43 percent were believed to have been impaired during the shooting; 88 percent were armed during the shooting; 26 percent stressed they wanted suicide by cop

How do cities compare in terms of officer-involved shootings?

Outcry over recent high-profile deaths of black men at the hands of police brought attention to the fact that data on officer-involved shootings is not uniformly tracked, so discrepancies in the numbers logged by federal and local agencies abound. A June article on the FBI’s website quoted Director James Comey’s talk at Georgetown the prior year, titled, “Hard Truths: Law Enforcement and Race.”

“How can we address concerns about officer-involved shootings if we do not have a reliable grasp on the demographics and circumstances of those incidents? We simply must improve the way we collect and analyze data to see the true nature of what’s happening in all of our communities.”

This week, Comey reportedly told Congress that the FBI will have a database tracking police use of deadly force functioning within the next two years.

The Washington Post took the initiative to create its own database “based on news reports, public records, social media and other sources.” Here are some compelling numbers for 2016:

People shot and killed by police in the United States – 2015: 991; 2016 YTD: 715

2016 officer-involved shooting fatalities in cities of comparable size – Albuquerque: 6; Tucson: 5; Milwaukee: 3; Oklahoma City: 3; Las Vegas: 2; Portland: 0

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy