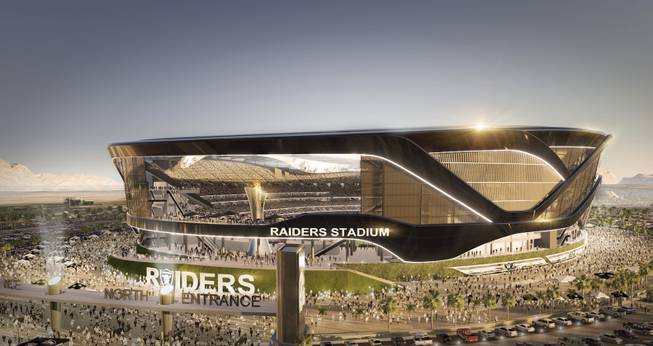

Courtesy of MANICA Architechture

An artist’s illustration of a stadium on Russell Road and Las Vegas Boulevard was revealed during a Southern Nevada Tourism Infrastructure Committee meeting at UNLV Thursday, Aug. 25, 2016.

Wednesday, March 22, 2017 | 2 a.m.

Related content

- Room-tax money for NFL stadium starts to flow before Raiders’ move finalized

- Lack of Las Vegas stadium lease not seen as barrier for NFL in Raiders’ move

- What’s behind the $1.9 billion price tag for NFL stadium in Las Vegas?

- NFL owners headed for showdown over Raiders move to Las Vegas

- Bank of America to fill funding gap for Raiders stadium in Las Vegas

- Jerry Jones reportedly finding investors to finance Raiders’ Las Vegas stadium

- Las Vegas Stadium Authority to tackle Raiders’ revised lease proposal next week

- Why Raiders are so confident about L.V. stadium financing

Blending scarlet and gray with silver and black on top of green will present a tricky art project at the proposed NFL football stadium in Las Vegas.

While most public discussion focuses on negotiations toward a lease agreement between the Oakland Raiders and the Las Vegas Stadium Authority board, another vital document offers as many questions and potential challenges.

UNLV and the Raiders will need to form a separate agreement on how the two entities will function together in the stadium. That shared use is required by Senate Bill 1, the state legislation that authorizes $750 million in public funding toward the $1.9 billion project. Lawmakers provided a substantial amount of the framework for discussions between the two sides, but no formal negotiations have taken place between the university and the team to date.

At the board’s March 9 meeting, Chairman Steve Hill said of his message to UNLV President Len Jessup, “It’s time to crank this up and work it out.”

“Given the importance of this issue, I don’t see us signing a lease with the Raiders without knowing that the agreement with UNLV is done,” Hill said this week. “I personally would not support that at this point.”

Hill said at the March 9 meeting that the lease agreement will not be completed in time for next week’s National Football League annual meetings in Phoenix, but that would not impede a potential vote of league owners on the team’s application to relocate to Las Vegas. He added that conversations on the lease continue between lawyers for the team and the authority, and will require at least two more board meetings for discussion.

Section 29 of SB1 spells out in detail scheduling procedures, stating the lease must “provide for the accommodation of a sufficient number of dates to host at the project the regular and postseason home games of the University football team.”

The Raiders receive priority in the law both as a tenant and an events company, as the law reads that dates must “not conflict with the use of the project by the National Football League team for a home game of the National Football League team” and “not conflict with major events that are not National Football League events that were scheduled to be hosted at the project before the University finalized the schedule of home games.”

The legislation also specifies that the team must agree on a “reasonable” rent to be paid by UNLV that “must not exceed the actual operational or pass-through costs, excluding any fixed costs, to host the game.”

Raiders President Marc Badain submitted to the board in January an initial lease proposal that was met with skepticism from the authority, the university and, most importantly, project investor Sheldon Adelson, who withdrew his $650 million investment in part because of his exclusion from the development of that first lease concept.

The draft document’s terms would allow the franchise to accept or reject not only potential UNLV football game times and dates, but other collegiate bowl games or showcase neutral-site contests as well. The conditions also stipulate that “under no circumstances shall field markings for the (Raiders) games be diminished or compromised in any way by the presence of collegiate football games of any kind.”

“The Raiders came in with an initial lease, and most people determined that there will need to be a lot of work in there,” said Gerry Bomotti, UNLV senior vice president for finance and business.

“They hadn’t consulted with us. The first time I’d seen it, my own opinion was that they borrowed it from some other location and didn’t really update it to be consistent with SB1. Our assumption was that that was not well thought through, in terms of intent to prevent UNLV from having a home-field advantage.”

Raiders officials did not respond to requests for comment on their perspective in discussions with UNLV.

Bomotti said the university’s primary concern in negotiations will be ensuring a home-field advantage for the Rebels inside a stadium where the Raiders control not only scheduling and field markings, but also naming rights and the facility’s day-to-day management.

“In particular, I think what we’ve highlighted is that we need to be able to create a UNLV gameday environment in that facility,” Bomotti said. “That isn’t totally spelled out, but what most people would think that means is when you come in there for a UNLV game, there has to be some scarlet and gray. When people are in there cheering for the team, they need to feel like it’s a home-field environment. I think that’s the last thing we would want to have a neutral-site environment.”

Bomotti also referenced “a whole host of other issues” for discussion including food and beverage, parking, tailgating, advertising, signage and access to VIP amenities like suites for major university donors. For instance, digital signage like ribbon boards and scoreboard can be adjusted easily from one day to the next, but fixed advertising and signs belonging to Raiders sponsors present less flexibility.

University officials submitted their markups on the Raiders’ first draft to stadium authority counsel but have not heard back from the team on that input.

Bomotti said Jessup has acted as the point person for the university in what Bomotti called numerous “episodic” conversations with the Raiders, consulting with him as well as athletics director Tina Kunzer-Murphy, head football coach Tony Sanchez and Thomas & Mack executive director Mike Newcomb.

“Our work so far with the Raiders really suggests to us that they want to work with us and they understand that we’re part of this stadium as well,” Bomotti said. “I think the legislators wanted to make sure we were accommodated in this stadium as well.”

Afforded a seat on the stadium authority board by SB1, Newcomb oversees both the Thomas & Mack Center and Sam Boyd Stadium — the current home of UNLV’s football team. Newcomb understands the potential hangups in shifting a facility from one team to another overnight, as could be the case with a UNLV game on Saturday and a Raiders game on Sunday.

Back when the Rebels shared Sam Boyd with the Las Vegas Locomotives of the now-defunct United Football League from 2009-2012, Newcomb’s crew of up to 70 people could clean the stadium and turn it from Locomotives’ colors on a Friday night to those of the Rebels on Saturday afternoon within six to eight hours. That included scrubbing out the paint from the Locomotives’ logo and preparing the field for the Rebels’ colors.

“The overall feeling from the university is, they want the ability when fans walk in to have a game-day experience that says UNLV, that doesn’t say you’re playing in someone else’s stadium, from the field, to the video board, to the cheerleaders,” Newcomb said. “The NFL’s coming to town and I think everyone doesn't want to lose sight of UNLV.”

Hill sees questions about game-day functions of the stadium as the primary piece to be worked out between UNLV and the Raiders.

“That’s probably the issue that will require the most thought,” Hill said. “That relates primarily to field markings. Given the digital age, changing signs is not too tough. The ability to operate everything else in the stadium will take some discussion, things like how do you deal with concessions and merchandise sales. There may be differences on what’s fair and what’s the right solution.”

Negotiations between UNLV and the Raiders also could focus on Oakland’s need for a temporary home at Sam Boyd for the 2018 and 2019 season, as the stadium project will not be completed until 2020 at the earliest. Sam Boyd would need enhancements that could include increasing its temporary capacity to 50,000 seats and improving outdated locker room facilities.

“We are prepared to upgrade Sam Boyd Stadium if we are asked,” Jessup said last month. “We’ll work with them to make that stadium ready.”

Bomotti said Raiders officials have toured the facility multiple times, but did not make any commitments about playing in a 35,500-seat stadium constructed in 1971 and renovated most recently in 2015.

“We don’t know what the Raiders are planning there,” Bomotti said. “Certainly that’s something that’s of interest to us.”

UNLV would join Miami (Miami Dolphins), Temple (Philadelphia Eagles), Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh Steelers), South Florida (Tampa Bay Buccaneers) and Tennessee State (Tennessee Titans) in shared stadium arrangements between universities and NFL franchises. Georgia State shared the Georgia Dome with the Atlanta Falcons until this season, as did San Diego State at Qualcomm Stadium with the San Diego Chargers. UMass also shared Gillette Stadium with the New England Patriots from 2012-16.

Details of those setups vary widely, though the franchises generally make out favorably on ancillary revenue like concessions and parking:

• Temple pays the Eagles $1.8 million per year for use of Lincoln Financial Field and does not receive any share of parking or concession revenue.

• Neither USF nor Miami pays rent, but the Bulls must cover direct costs of up to $185,000 per game for use of the lower bowl and two club lounges, and the Hurricanes share some revenues at Sun Life Stadium.

• The Titans are required by law to allow Tennessee State to play at Nissan Stadium after receiving more than $200 million in public funding.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy