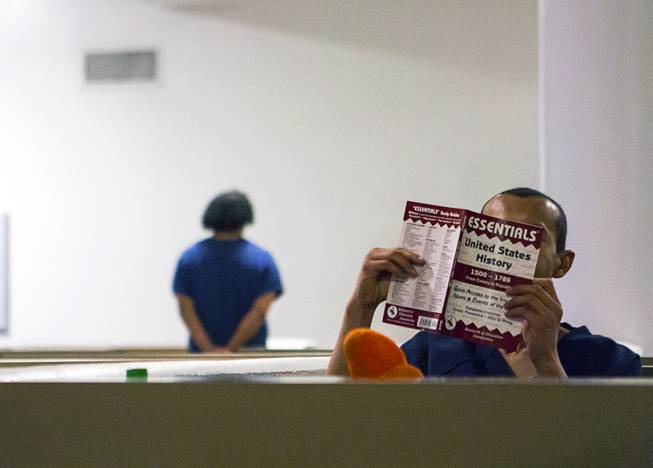

Miranda Alam / Special to The Sun

An inmate reads at the Clark County Detention Center in downtown Las Vegas on Wednesday, May 16, 2018.

Saturday, May 19, 2018 | 2 a.m.

On Wednesday afternoon, the inmates slept, read and chatted in one of the open housing units. In another, a medic accompanied by two officers went room to room, administering medication. And in a higher-security section, officers kept an eye on the internees on monitors and by conducting walk-throughs every 15 minutes.

As is increasingly the case in jails across the U.S., the Clark County Detention Center has become the largest mental health facility in the valley, or “ground zero” as an official referred to it Wednesday during a presentation and tour of the facility, which has identified up to a quarter of its population as taking medications for mental illness.

The majority of the inmates with those issues are placed in specialized housing units. But many of them are landing in jail on minor offenses, and their short stays can “exacerbate their symptoms,” said Metro Police Capt. Nita Schmidt during the "Stepping Up: A Day of Action" initiative presentation. “In many cases, it can increase the likelihood of recidivism.”

Clark County in 2015 became one of the roughly 415 jurisdictions (across 43 states) that passed a resolution to bring awareness to and address the problem.

This calls for the county jail to "create sustainable, systems-level policy and practice changes to better link people to treatment services while improving public safety."

The jail houses 4,498 total inmates. Last year, it conducted more than 11,000 mental health assessments, providing almost 40,000 mental health visits and drafting 5,042 discharge plans.

With about 70 percent of its population spending eight days or less behind bars, finding those services is a challenge, Schmidt said.

In any case, there are not enough mental-health programs available in the community or the state to effectively combat the epidemic, and something is happening between the time the inmates are released and when they re-offend, Schmidt said. “The cycle needs to be broken.”

When the county joined the initiative three years ago, it started looking at revising its policies and taking a look more broadly, Schmidt said. Data-driven programs, funding, and new policies can help alleviate the problem.

For now, officials have increased their collaboration with the District Attorney's Office, the court system and experts across the country to find solutions to deter the people from landing in jail in the first place. At the jail, there are the re-entry programs, and Metro Police, which operates the facility, is in a committee on mental health, in which they're searching for those solutions.

So far, a lot of the efforts have been research-based, learning from programs from other jurisdictions. And what officials have gathered can be used to potentially enact changes in upcoming legislative sessions.

"It's not about starting a new program or more bed space," Schmidt said. "It's about looking at system-level practices and ways that you can make effective change being fiscally responsible."