A sign, designed as an oversized bucket, in Baker, Nev. promotes opposition to a proposed water pipeline to Southern Nevada in this Sept. 15, 2016 file photo.

Friday, Nov. 1, 2019 | 2 a.m.

About a dozen regional organizations, tribes and government bodies are opposing elements of Clark County’s proposed public lands bill, arguing that the current language would facilitate the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s controversial water pipeline project.

Water authority and county officials’ responses have been blunt: The opposition is not based in fact.

Clark County has been working on the federal public lands bill, officially known as the Southern Nevada Economic Development and Conservation Act, for the last several years. The draft legislation, which would broadly create new conservation areas in Clark County and expand the county’s developmental boundaries, is now in the hands of Nevada’s congressional delegation.

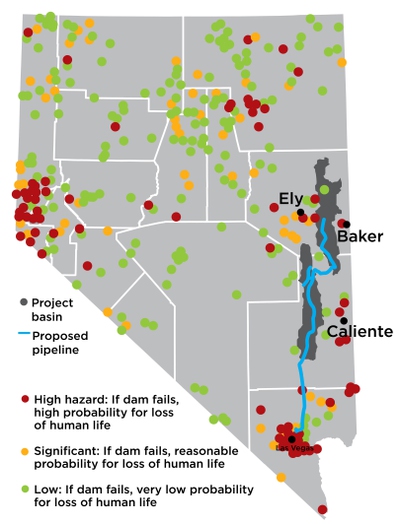

Two sections of the bill relate to the water authority and have caught the ire of opponents of the agency’s water pipeline project. First devised in 1989, the proposal calls for the construction of a series of buried pipelines that would collect groundwater in White Pine, Lincoln and rural Clark counties and pump it to the Las Vegas area.

Section 703 directs the secretary of the interior to convey federal lands to the water authority that already contain water infrastructure managed by the agency, “for public purposes.”

Section 702 of the lands bill would grant the water authority a right of way to federal land in Lincoln and Clark counties “for construction and operation of a power line,” specifically the proposed Eastern Nevada Transmission Project. The geographic extent of that right of way would reflect two previously granted rights of way, one of which is the same Bureau of Land Management right of way and environmental assessment for the pipeline project.

In August 2017, a federal judge directed the BLM to revise that environmental assessment.

"That's the connection right there and that’s why we’re calling this pro-pipeline," said Kyle Roerink, executive director of Great Basin Water Network.

Both sections state that the rights of way and the transfer of federal lands would not be subject to “further judicial or administrative review.” Although neither section refers specifically to a water pipeline, opposing organizations interpret them as green lights for the water authority’s long-awaited pipeline and as tools for the authority to sidestep oversight.

“Section (702) says the right of way granted to the water authority shall be subject to those terms and would not be subject to further judicial review,” Roerink said. “From our perspective, we see this as an end-run exemption.”

Bronson Mack, spokesperson for the water authority, said that that interpretation couldn’t be further from the truth.

“This doesn’t have any bearing or implications at all for the development of groundwater resources in the state of Nevada,” Mack said.

Marci Henson, director of the Clark County Department of Air Quality that spearheaded the bill, said critics were misunderstanding these sections, which relate to the transmission of renewable energy. Clark County Commissioner Justin Jones, who sits on the water authority’s board of directors, also denied any connection to the pipeline project.

“We don’t see how that language included in the bill would in any way facilitate, enable or exclude the pipeline from further administrative or judicial review,” Henson said.

Most of the entities opposing Sections 702 and 703 of the lands bill, such as the Great Basin Water Network, the White Pine County Commission, the Ely Shoshone Tribe and the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, have been fighting the pipeline project through the courts for more than a decade.

The proposed SNWA pipeline would stretch 300 miles from Las Vegas to areas near the Great Basin, where the water authority owns 23,000 acres of land and more than 100,000 acre-feet of water rights. Architects of the plan envisioned pumping water south if resources were to grow scarce. But the Great Basin Water Network challenged SNWA’s permits for the water rights, and the issue is still tied up in court.

Juab and Millard counties in western Utah also oppose the language in the draft public lands bill because of supposed pipeline implications, according to Great Basin Water Network. The two counties are parties in litigation against the project due to potential effects on groundwater near the Nevada-Utah border.

On Tuesday, another entity not involved in the litigation came out against the language in the public lands bill: The Salt Lake County Council. The council voted to send a letter to Sen. Catherine Cortez-Masto, D-Nev., urging her to reject the proposed legislation as written.

The council contends that the bill language would allow the water authority to skirt environmental review for the pipeline project, which would harm Great Basin National Park and Salt Lake City in northern Utah, according to the council.

“The removal of groundwater from this area would lead to the die-off of vegetation in the area and would increase the frequency and severity of dust storms that would negatively impact the air quality in Salt Lake City and health of its residents,” Council Chair Richard Snelgrove wrote in the letter.

The water authority has long argued that the pipeline project is necessary to address population growth in Las Vegas and declining water levels at Lake Mead. However, Clark County’s proposed public lands bill has nothing to do with the project, nor would it allow the agency to circumvent environmental reviews associated with it, Mack emphasized.

“The Eastern Nevada Transmission project and the combining of these two right-of-ways will help facilitate the development and transmission of renewable energy and renewable resources into Southern Nevada,” Mack said.

Although Mack believes the bill language is sufficiently clear, the county has modified the language in those sections for clarity in the last several months, Henson said. It might be tweaked even more in response to continued concerns.