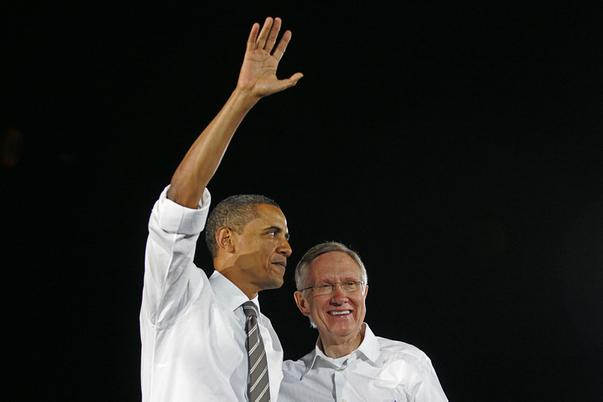

Stephen Crowley / The New York Times

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, shown in his office on Capitol Hill in Washington in 2014, died on Tuesday, Dec. 28, 2021, in Henderson.

Published Tuesday, Dec. 28, 2021 | 5:02 p.m.

Updated Tuesday, Dec. 28, 2021 | 8:09 p.m.

Harry Reid never felt the need to be loud or brash. The former U.S. Senate majority leader who died Tuesday in Henderson at age 82 instead often took a soft-spoken approach to politics that resulted in effective, lasting and historic results.

The Searchlight native represented Nevada for 30 years in the Senate, where his even-keeled approach was vital in helping broker the Affordable Care Act, thwarting a proposed nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain and fostering laws to preserve public lands and encourage clean energy investment.

Along the way he became a key player in the Democratic Party, encouraging then-Sen. Barack Obama to run for president and advocating for immigration reform. Following Reid's retirement in 2017, he continued to wield power from behind the scenes, advising candidates running for office and remaining outspoken on current affairs.

The Reid Machine helped flip Nevada from a state controlled by Republicans to a Democratic majority in the Statehouse and paved the way for the Democratic presidential nominee to win the state in the past four elections.

Related content

Along the way, Harry Mason Reid became the longest serving U.S. senator from Nevada and majority leader for eight years.

His legendary career in public service was recently memorialized when the name of the Las Vegas airport was changed to Harry Reid International. Private donors are raising $7 million for the rebranding, which started this month.

His wife of 62 years, Landra, said she was heartbroken to announce his passing. He died peacefully surrounded by family after a four-year battle with pancreatic cancer, she said.

“We are so proud of the legacy he leaves behind both on the national stage and his beloved Nevada,” she said. “Harry was deeply touched to see his decades of service to Nevada honored in recent weeks with the renaming of Las Vegas’ airport in his honor.”

Funeral arrangements will be announced in the coming days, she said.

President Joe Biden, who worked with Reid for two decades in the Senate and eight years while Biden was vice president, said Reid was always a man of his word.

“If Harry said he would do something, he did it. If he gave you his word, you could bank on it. That’s how he got things done for the good of the country for decades,” Biden said in a statement.

The president listed a number of Reid’s accomplishments, including helping pass Obamacare and legislation to save the economy, Wall Street reform and blocking efforts to privatize Social Security.

“I’ve had the honor of serving with some of the all-time great senate majority leaders in our history. Harry Reid was one of them. And for Harry, it wasn’t about power for power’s sake. It was about the power to do right for the people,” Biden said.

“May God bless Harry Reid, a dear friend and a giant of our history,” Biden said.

Former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton also issued statements honoring Reid, Obama sharing via Twitter a personal note he recently sent the former senator.

Obama said Reid was “more generous to me than I had any right to expect,” and credited him with making possible his presidency and accomplishments.

“As different as we are, I think we both saw something of ourselves in each other — a couple of outsiders who had defied the odds and knew how to take a punch and cared about the little guy. And you know what, we made for a pretty good team,” Obama said.

Clinton called Reid “a canny and tough negotiator who was never afraid to make an unpopular decision if it meant getting something done that was right for the country.”

“Ever the boxer of his youth, he never shied away from necessary political fights, but believed compromise is vital for a functioning democracy,” Clinton said.

Reid’s lengthy service started at age 28 in 1968 when he was elected to the Nevada Assembly and served two terms. He was also Nevada’s lieutenant governor, chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission who played a major role in driving the mob out of Las Vegas casinos, and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for two terms. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1987, rising to the role of Senate majority leader from 2007 to 2015.

“The little boy of Searchlight has been able to be a part of a changing state of Nevada,” Reid said in his farewell on the Senate floor in December 2016. “I’m grateful I’ve been a part of that change.”

The most significant change was arguably his opposition to Yucca Mountain, which in 1982 when Reid was elected to the House was pegged as a dumping ground for the nation’s nuclear waste. By the time he left Washington in 2017 after 34 years in Congress, the site 90 miles from Las Vegas was nothing more than a shuttered hole after a decades-long fight.

Along the way, Reid’s public lands agenda helped take Nevada from 67,000 acres of wilderness to more than 4 million acres of new parks and open spaces when he left office.

When Reid retired, Nevada Democratic Rep. Dina Titus said, “He is very soft-spoken, but sometimes that’s a good ploy because you have to lean in to listen to what he has to say, and it gives him an advantage in any kind of negotiation. He’s definitely good in the trenches behind the scenes.”

Reid, a man of average height and slender, athletic build, maintained a steady exercise regimen while in Congress and appeared to be in the same good physical condition he was as an amateur boxer in the 1950s at Basic High School. He was coached by then-history teacher and future two-term Nevada Democratic Gov. Mike O’Callaghan, who served as Reid’s mentor and best friend, helping him launch a career in politics.

Reid long retained the same fair skin tone that earned him the boyhood nickname of “Pinky,” which when combined with one of the various pairs of small wired glasses he wore just off the bridge of his nose, gave him a kind, grandfatherly look.

In a gray business suit and those specs, one would easily take Reid for a stodgy, indistinctive accountant or perhaps even a lawyer, which by trade he was. His facial expressions ranged from a wide toothy smile to a wry, sly grin with a distinctive look of “I told you so.”

Perhaps the singular characteristic for which Reid was most well-known was his soft voice that rarely fluctuated, even when addressing issues that excited him or raised his ire.

Although Reid often spoke in almost a whisper, people never strained to hear what he had to say because his opinion, especially on Capitol Hill matters, was greatly respected.

Former Sun reporter Lisa Mascaro, in a 2007 Sun story when Reid became majority leader, opined on why Reid generally talked so softly: “Some people use a stage whisper for the let-me-tell-you-a-secret effect. Reid seems to do it because that’s the way his diaphragm works. Rather than summon his voice from somewhere deep within him, he releases it from the tip of his tongue.”

Humble beginnings

Born Dec. 2, 1939, in Searchlight, 49 miles southeast of Henderson, Reid was the third of four sons of Inez Orena, a laundress, and Harry Vincent Reid, a miner. Reid grew up in a two-bedroom dilapidated shack that had no indoor toilet, no hot water and no telephone.

He attended a two-room elementary school that had just one teacher for all eight grades. It was in that tiny schoolhouse that Reid learned such values as hard work and a sense of independence — characteristics that would pave the way for his success in law and politics.

As a youngster, “Pinky” Reid, when not attending classes, would accompany his father for long work days underground in the dusty desert mines.

Verlie Doing, longtime owner of the Searchlight Nugget in the heart of the town and who died in 2016, credited the simple, rural lifestyle of Searchlight for molding Reid as a down-to-earth everyman during his formative years. “Harry loves walking through the hills here to clear his mind,” Doing said in a Sun story. “As a youngster he would walk for hours and come home where his mom, Inez, made him a big pot of pinto beans.”

Reid’s parents were both heavy drinkers and died before his meteoric rise in politics. His father committed suicide when Reid was 33 and his mother died six years later in 1978. They are buried side-by-side in the family plot in Searchlight’s 100-plus-year-old, tumbleweed-lined cemetery east of town, where many years earlier young Harry had helped his father dig graves in the rocky soil to bring in extra income for the family.

For most of his life, he proudly counted himself among the 800-plus population of Searchlight, a town that is bisected by a one-mile stretch of U.S. 95 from the community church on the north end and a McDonald’s fast-food restaurant to the south.

Because Searchlight has no high school, Reid, as a teenager, boarded with relatives in Henderson on weekdays to attend Basic High School, where he played football and was an amateur boxer.

It was also at Basic High where Reid met then-sophomore Landra Gould, who became his high school sweetheart. In his senior year, Reid was elected student body president — his doorway into politics.

In 1959, two years after they graduated from high school, Harry and Landra married. In 1961, their first child and only daughter, Lana, was born. Son Rory was born in 1962, and three more sons — Leif, Josh and Key — followed.

Reid was able to attend college on a scholarship that was arranged by O’Callaghan and co-financed by area businessmen who believed Reid had great potential for a bright future.

Reid earned an associate of arts degree from Southern Utah University in 1959 and graduated from Utah State University in 1961 with bachelor’s degrees in political science and history. Reid also minored in economics at Jon M. Huntsman School of Business at Utah State.

Reid’s next step was to go to Washington, D.C., to earn a law degree from George Washington University. The summer before Reid left for the nation’s capital, O’Callaghan made phone calls to high-placed friends in Washington and got Reid a patronage job as a Capitol police officer working nights for four years to help Reid pay for law school and support his young family.

In Reid’s 2009 autobiography, “The Good Fight: Hard Lessons from Searchlight to Washington” written with then-Esquire Magazine Executive Editor Mark Warren, Reid writes in the dedication that O’Callaghan was “an inspiration to me in his life’s example and still an inspiration in death.”

In 1963, with one more year of law school to attend, Reid petitioned the Nevada Supreme Court to allow him to take the state bar examination. The court approved Reid’s request. He flew home, took the test and passed.

Law career

After earning his law degree in 1964, Reid and his family moved from Washington to Henderson, where he served as the city attorney, revising the city charter and working on extending Henderson’s boundaries by acquiring federal land.

Reid was elected to the Nevada Assembly in 1968 at age 28.

In Carson City, he introduced the first air pollution legislation in Nevada’s history and also worked to protect consumers, including a bill requiring utility companies to pay interest on large deposits they demanded from customers. Both bills became Nevada law.

In 1970, at age 30, Reid was chosen by gubernatorial hopeful O’Callaghan as his running mate. They won and Reid served as lieutenant governor from 1971 to 1974, the youngest in Nevada history. In 1974, Reid opted to run for the U.S. Senate seat vacated by Alan Bible.

Reid, who ran a negative campaign against former Republican Nevada Gov. Paul Laxalt and later admitted that he regretted it, lost by 611 votes. In 1975, Reid ran for mayor of Las Vegas and lost in a landslide to Bill Briare.

After spending a couple of years as a private practice attorney, Reid’s public service career was kick-started by his friend, Gov. O’Callaghan, who in 1977 appointed Reid as chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission, succeeding Peter Echeverria.

There, for five years, Reid made headlines for his unrelenting crusade to remove once and for all organized crime’s influence over the state’s gaming industry. They were secretly wielding their influence over major Las Vegas resorts to skim profits from the lucrative casino operations by using frontmen with clean records to pose as the new resort owners. One such mob plant was Allen Glick, whose Argent Corp. purchased the Stardust and Fremont hotels.

The mob’s overseer of the casino skimming operation was sports tout and convicted game fixer Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal.

To avoid having to apply for — and undoubtedly be turned down for a gaming license — Rosenthal took various bogus titles at the Stardust, including entertainment director and food and beverage manager. However, in 1976, gaming authorities, suspicious that Rosenthal indeed had a vital role in running the casino, forced him to apply for a state gaming license.

In December 1978, Rosenthal appeared before Reid and the other four members of the gaming commission, which voted unanimously to deny Rosenthal’s application because of Rosenthal’s past criminal convictions.

After the hearing, Rosenthal went into a rage, accusing Reid of, among other things, having had a complimentary lunch at the Stardust. Reid recalled the lunch, but said that because he wasn’t on the gaming commission at that time there was no impropriety.

Rosenthal’s showdown with Reid was depicted in the 1995 Martin Scorsese film “Casino.”

Glick, Rosenthal and Tony Spilotro — the Chicago mob's overseer in Las Vegas — were thrown out of the gaming industry and the Stardust and Fremont eventually were purchased and operated by Boyd Gaming.

Reid never backed down from his efforts to throw the mob out of Las Vegas, as mob associate Joe Agosto, in FBI surveillance tapes, referred to Reid as “Mr. Clean Face.”

Reid’s work is credited with initiating the beginning of the end of organized crime’s influence in Nevada’s gaming industry. In 1981, then-Gov. Robert List, a Republican, asked Reid to stay on as gaming chairman, but Reid declined and left office in April. He had bigger dreams to fulfill.

Reid goes to Washington

Reid won the Democratic nomination for the House of Representatives in 1982 then easily captured the general election by defeating Republican Peggy Cavnar. He served two terms in the House, from 1983 to 1987. There, Reid fought for a Taxpayer Bill of Rights and introduced legislation to protect Nevada’s wilderness.

In 1986, Reid won the Democratic nomination for the seat of retiring two-term incumbent Republican Sen. Laxalt. He defeated former Congressman Jim Santini, a Democrat-turned-Republican, in the November election. One of Reid’s first acts was establishing the Great Basin National Park — the state’s first national park — and securing other new wilderness areas in Nevada, including restoring the clarity of Lake Tahoe.

Reid easily won reelection in 1992. But, six years later, he struggled to barely defeat GOP Rep. John Ensign. In 2004, Reid won reelection to his Senate seat with 61% of the vote. In 2010, Reid comfortably won reelection after a bitter campaign where the Tea Party had targeted him.

On Capitol Hill, Reid long was regarded as a tireless worker. It was not unusual for him to be the first senator to arrive at work in the morning and the last to go home at night. Such dedication certainly played a role in Reid’s ascension to leadership positions.

From 1999 to 2005, Reid served as Senate Democratic whip — minority whip from 1999 to 2001 and again from 2003 to 2005 and majority whip from 2001 to 2003. Also from 2001 to 2003, he served as chairman of the Senate Ethics Committee.

Reid took the Senate Democrat leadership role at a time when the GOP controlled the White House and Congress, but he was not afraid to criticize then-President George W. Bush when political situations called for it — especially in managing the war in the Middle East.

Reid voted in 1991 to authorize the first Gulf War, and in 2003 he voted to support the invasion of Iraq. But in 2007, Reid changed course and started to support an alternate strategy that centered on the timely withdrawal of troops from the Middle East.

Reid’s change of heart, he said, came after visiting badly wounded American soldiers at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in late March of 2007. He called it his “Walter Reed moment.”

Weeks later, Reid voted to redeploy U.S. troops out of Iraq by March 2008, a motion that failed. Later that year, Reid said, “As long as we follow (President Bush’s) path in Iraq, the war is lost.”

Reid told the Sun, “I don’t want to wait 60 days, have scores more killed, hundreds more wounded. I simply believe this is a bad situation, a foreign-policy blunder that’s going to take generations to overcome. It’s destabilized the Middle East and the world, and I want to be remembered as somebody who tried to change that.”

The war issue provided fodder for Reid’s biting criticisms of Bush, a man Reid would call in his 2009 memoir “among the worst — if not the worst — (president) in the history of our country.”

Opposing Yucca Mountain

Reid achieved hero status among many Nevadans for his fight against the proposed Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository. Starting with passage of the so-called “Screw Nevada Bill” in 1987, Reid devoted countless resources to ensuring that the purported done-deal project would never come to fruition.

His success was a phenomenal feat by any yardstick, as Reid had to overcome opposition from other, more seasoned and more powerful lawmakers and the dogged efforts and vast monetary resources of the Department of Energy that oversaw development of the Yucca Mountain site.

“What gave us the passion to fight the dump was the manifest injustice of it all,” said former Nevada Democratic Sen. Richard Bryan, who began fighting against Yucca as governor and later joined Reid when both were senators. “What enraged Harry, and certainly me, was that Nevada was treated like the harlot on the street — that somehow we had some price that we would take for the nuclear dump. It was so offensive.

“But the ultimate reason for opposing it was the health and safety issue,” Bryan said. “Harry and I came from the above-ground nuclear weapons testing era in the Nevada desert where we were constantly being assured that everything would be fine, and of course, it was not.”

As Reid rose to prominence in the Senate, he gained the power to first cut funding for the project. Then, during the heat of a presidential race, he gained a commitment from candidate and later President Barack Obama to kill the project outright.

But in the face of polls in 2010 that said Reid’s popularity was seriously waning, there was speculation that Reid, even after garnering 75% of the vote in the June primary, was in danger of losing his seat that November to new broom GOP Tea Party candidate Sharron Angle.

It seemed so bleak for Reid’s campaign, that he felt he had to “reintroduce himself” to the state’s 400,000 new voters — retelling the story of a dirt-poor kid from a sagebrush-blown town who was raised in a shack and beat all odds.

The great irony was that the lawmaker who once ran on the slogan “Independent Like Nevada” was forced to remind voters he was still one of them — still independent — and that he had not lost touch with them. For all of the gloom and doom buildup fueled in part by faulty polls, the 2010 election turned out to be no different and Reid routed Angle.

Reid often reached across the aisle to hammer out compromises, while rarely, if ever, compromising his principles or his ideals. Some of his Republican colleagues over the years praised his reasoned, balanced approach.

Revered Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch once said Reid was “one of the moderate voices around here who tries to get things to work.”

Former Republican Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi once said, “Harry Reid is out there finding a solution.” In 2003, Lott told the congressional newspaper The Hill, “I think Harry comes off as soothing in some respects.”

Still, Reid had plenty of critics.

Reid, once praised as a master of brokering deals to Nevada’s gain, became the target of pundits who said Reid, after ascending to the top echelon of his political field, had begun to ignore the people of Nevada who had put him in Washington in the first place.

At times Reid, the moderate, was damned if he did and damned if he didn’t.

Conservatives labeled Reid a liberal along the lines of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and blasted him for saying things like the Bush-run War in Iraq was destined to fail.

Liberals argued that Reid was too conservative, saying that, despite his great clout, he failed to bring a swift end to the war, that he supported gun owners’ rights over the banning of assault weapons and that he backed the gold mining industry’s interests over environmental concerns.

Avid supporter of Obamacare

Of all of Reid’s accomplishments, he said helping Obama pass the Affordable Care Act ranked highest.

In his final address in the Senate, Reid said it would have been “wonderful” if the law had existed when he was growing up in Searchlight.

“We didn’t go to doctors. It was a rare, rare occasion,” Reid said. “There was no one to go to.”

Reid often shared the story of how he worked at a service station as a kid to save $250 to buy his mother teeth. He called it the “one thing I did in my life that I am so proud of.”

He also talked frankly about how his father struggled with mental health issues before committing suicide.

“I think everyone can understand just a little bit why I’ve been such an avid supporter of Obamacare, health care,” Reid said.

The act, which was signed into law in 2010, has long faced resistance from Republicans. When speaking about the value of the law a few years ago at a Las Vegas event, Reid stressed that “a great nation can’t have upwards of 40 million to 50 million people with no way to go to a hospital or see a doctor.”

He continued, “Throughout our history, we’ve had presidents wrestle with how to provide better health care. Obamacare is anything but socialized medicine. It’s more about access to insurance — and a lot of people didn’t like that. What we’re trying to do is enable everybody to have the same health insurance as I have.”

Reid is credited with working to secure the Senate Democrats’ 60-vote majority to pass the bill, including a vote from Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman, who had endorsed Arizona’s John McCain over Obama in the 2008 election.

Vox, in the 2015 article “Obama has Harry Reid to thank for his biggest accomplishments,” wrote that the act passed “because Harry Reid managed something that seemed almost unthinkable: he held every single Senate Democrat — 60 of them, at least at the crucial moment — together to vote for a sprawling, unpopular bill that raised taxes, cut Medicare spending, and insured tens of millions of Americans.”

Along the way, there were many failed attempts by Republicans to remove the law or eliminate its funding. In a 2014 budget fight, when House Republicans threatened to ax the Obamacare budget in exchange for keeping the rest of the federal government funded, Reid responded: “Any bill that defunds Obamacare is dead — dead.”

And so the act lives on, with more and more residents getting health care each year.