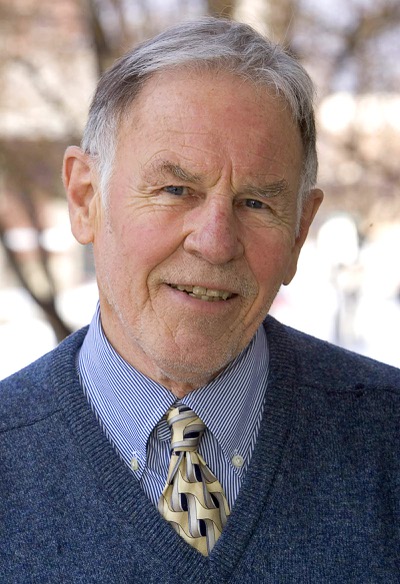

R. Marsh Starks

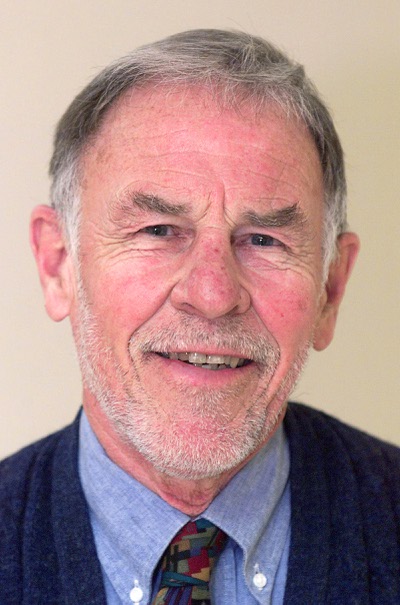

Former Las Vegas Sun reporter Cy Ryan is shown in the State Capitol building in Carson City, June 29, 2006. Ryan died Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021, at age 88.

Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021 | 6:30 p.m.

When former Nevada Gov. Jim Gibbons called a 2008 news conference to try to explain why he had made hundreds of texts, many late at night, from a state-issued cellphone to a woman who was not his wife, Sun Capitol Bureau Chief Cy Ryan cut right to the chase.

“Were these love notes?” Ryan asked. “No,” Gibbons answered. “How many times did you sleep with her?” Ryan asked. “None,” Gibbons answered.

When former Nevada Gov. Paul Laxalt suddenly dropped out of the 1988 presidential race and went to his Marlette Lake retreat deep in the Sierra Mountains, Ryan hiked up the mountain to ask the secluded Laxalt several questions, including how much the published allegations that Laxalt had mob ties played in the Republican front-runner’s decision to bow out.

No question was off-base, too embarrassing or too tough for Cy Ryan to ask, earning him the reputation of a dogged reporter who would overcome any obstacle to get his story.

Robert Dominic “Cy” Ryan, a Nevada Newspaper Hall of Fame inductee who spent more than a half-century covering the Nevada Legislature and Northern Nevada, first for United Press International and then for 26 years for the Las Vegas Sun before retiring in 2017, died Thursday. He was 88.

Ryan’s virtual plaque in the Nevada Press Association’s online Newspaper Hall of Fame, describes him as “a hard-nosed reporter and workhorse … a capitol press corps legend.”

So respected was Ryan in his field that his fiercest rival, Ed Vogel, the Capitol Bureau chief for the Las Vegas Review-Journal, nominated Ryan for induction into the state journalism shrine.

“(Ryan) is an old-fashioned newspaperman who doesn’t take any crap from politicians,” Vogel wrote in his June 30, 1999, nomination letter, praising Ryan for working long hours each weekday, giving up his weekends to track down stories and for often refusing to take vacations.

“People think of Mark Twain when they think of Nevada newspapermen. I think of Cy Ryan.”

Ryan worked in the press corps at the statehouse during the tenures of nine governors — five Republicans and four Democrats — starting with the late Grant Sawyer and ending with Brian Sandoval.

"Nevada has lost one of its journalistic giants with the passing of longtime @UPI and @LasVegasSun Capital Bureau Chief Cy Ryan," Sandoval tweeted. "You could never outwork this wonderful man who was uncompromisingly true to all of the tenets of his profession. He was one of a kind."

Nevada's current governor, Steve Sisolak, also took to Twitter: “This is very sad news. Cy Ryan was a wonderful reporter. Kathy and I send our love and condolences to his family and friends during this difficult time.”

At no time was Ryan more on his game than at a news conference Gibbons called in June 2008 to try to explain away evidence that pointed to him cheating on wife Dawn with the former wife of a Reno podiatrist and mother of seven, Kathy Karrasch.

When Gibbons, who had only been in office for 18 months, told the press that Karrasch, to whom he had sent 867 text messages in six weeks during 2007, was just a platonic friend, that was not good enough for Ryan.

After the embarrassing questions were asked, Gibbons admitted: “It’s one of those things, when I look back and see there were six weeks of text messages, it wasn’t the brightest — it wasn’t something I should’ve done. It was a mistake.”

Still, Gibbons said that most of his texting dealt with state business, prompting Ryan to ask what issues she advised him on, to which Gibbons responded, “Taxation.” Ryan retorted, “In what way? You said no new taxes.”

“That’s true, but there’s a number of things, heck, even personnel management things,” said Gibbons, getting obviously flustered.

Gibbons eventually divorced his wife of 22 years, former Assemblywoman Dawn Gibbons, citing “incompatibility.” In a motion, the former first lady said the governor wanted a divorce because he had been involved with another woman. Several news sources said that woman was Karrasch, proving that Ryan undoubtedly was barking up the right tree with his queries.

Twenty years earlier, Ryan, an accomplished athlete, put on his hiking boots to get a quote.

After Chris Chrystal, a former Sun city editor then working as a UPI reporter in Washington, D.C., broke a story quoting sources as saying that Laxalt, Ronald Reagan’s heir apparent to the White House, had dropped out of the race, Ryan was charged with getting an explanation.

When Ryan got to up the mountain retreat and found Laxalt, the GOP standout declined to answer Ryan’s barrage of questions, including if the mob-ties allegations spurred Laxalt’s quick exit. Ryan then descended the mountain, got to a pay phone and filed the “no comment” story.

“That shows just how committed Cy was to getting a story — walking up and down a steep mountain with no roads; generally accessible only by helicopter,” Ryan’s former UPI colleague Myram Borders said. “Cy was persistent. He would go to any length to do his job.”

Although Laxalt later won a lawsuit against the newspaper that originally reported his ties to organized crime and later admitted he quit the presidential race because he had come up short on his fundraising goals, Ryan’s efforts to reach Laxalt earned him the reputation of holding politicians’ feet to the fire. And his tenaciousness drew praise from other noted contemporaries.

“Although he had opportunities to move up the ladder of his profession to become an editor, a manager or a newspaper executive, Cy chose the honorable path of remaining a great reporter,” said Warren Lerude, former editor and publisher of the Reno Evening Gazette and Nevada State Journal who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1977.

“A newspaper cannot rise above the level of its reporters, and Cy was the kind of reporter who could smell good stories about politicians erring and go after them with great fervor.”

David Schwartz, who worked with Ryan at the statehouse for the Sun starting in the 2000s, remembered Ryan as someone who wasn’t afraid to ask a tough question. He earned the respect of lawmakers for holding all to the same standard.

“He had that sense of fairness about him that everyone knew he was asking those questions for the right reason,” Schwartz said.

Ryan kept most people at an arm’s length, but developed a fondness for Schwartz — he even spent the holiday with Schwartz’s family and “was great with my kids.” Schwartz moved to New York but would frequently call Ryan to check on his well-being.

On Facebook, Schwartz posted, “For five years we worked across from each other in offices in the Capitol basement. He’d tell me to hurry up and get the stories out, and I wrote too long — issues I don’t know if I ever fixed. He’d also offer me advice on family, and tell me to get to Mass.”

It is not clear how Ryan got the nickname “Cy."

”One story, Lerude said, came from their college days when classmates teased Ryan about the many speeding citations he got from cops while driving a cab in Carson City. They called him Cy for short.

However, Lerude, a fellow Nevada newspaper Hall of Famer, noted there is no real evidence that Ryan ever drove a taxi at any time in his life or that he ever was issued an inordinate number of traffic citations.

Another story is that Ryan got his nickname from one of his early editors, possibly the late Russell Nielsen, who spent 30 years as the Reno-based Nevada UPI manager. Ryan was purported to be so quick at filing his stories that he reminded his editor of the speedy thoroughbred Citation — again, Cy, for short.

Schwartz said he heard that Ryan indeed got the nickname as a comparison to that speedy equine, but its use was sarcastic, coming from his bartender days when Ryan was slow at mixing drinks.

Once asked by a Sun colleague if the nickname stemmed from comparison to the great race horse, Ryan just grinned and walked away.

And while newspapermen are notorious for having messy offices, Cy abused the privilege.

Ryan’s Carson City office was, to put it politely, a dump. An athletic supporter and an unused toilet seat were among the office accouterments. Stacks of newspapers, some dating back decades, were piled like desert rock formations on the floor. His desk was covered with, among other things, old Supreme Court decisions that a busy Ryan would turn over and use as note paper.

Ryan often filed his expense reports on old UPI envelopes. On his door was a faded, tongue-in-cheek proclamation from a former governor in honor of Cy.

Ryan was born Feb. 15, 1932, and grew up in California where he attended Christian Brothers Catholic High School in Sacramento. A Navy veteran of the Korean War, Ryan often spoke of serving overseas with Boston Red Sox great Ted Williams, a Marine pilot who was stationed at an airfield in Pohang, South Korea in 1952 and ’53.

After the war, Ryan moved to Carson City where he worked as a bartender at Harold’s Club to raise money to help put himself through the UNR School of Journalism, today known as the Reynolds School of Journalism. There, Ryan and Lerude were students of Nevada journalism teaching legend A.L. “Higgy” Higginbotham, who produced three Pulitzer Prize winners.

While at UNR, Ryan won a national essay contest, writing about the small island nation of Cuba and received a free week’s vacation there at a time when the capital city of Havana was home to lavish mobster-run casinos and had a nightlife similar to that of Las Vegas.

But during that vacation in early 1959, Ryan found himself caught up in the Communist Revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power and led to the shutting down of all of the Havana casinos. Lerude, who at the time was editor of the Sagebrush student newspaper, said Ryan, while in Cuba, became that publication’s “first — and likely last — ‘foreign’ correspondent.”

After graduating from UNR in 1960 with a bachelor's degree in journalism, Ryan almost immediately was hired by UPI and for the next several decades covered milestone events in the state’s colorful history.

In 1964, Ryan trekked to the Humboldt County ranch of ex-state assemblyman Phil Tobin to get his views on gaming some 30 years after Tobin authored and pushed through the landmark Wide Open Gambling Bill that forever changed the course of the Silver State.

“I don’t think it’s right, allowing these one-armed bandits (slot machines) in every supermarket ... and restaurant in the state,” the cantankerous old cowboy told the young reporter. Tobin believed that to stem the proliferation of gaming just casinos should have devices of chance.

If not for Cy Ryan, we might never have known that the Father of Modern Nevada Gambling was upset over such a consequence resulting from his dream of legalizing gaming to encourage tourism, entice tax revenue and get his state out of the grips of the Great Depression.

Among Ryan’s many duties for UPI and later for the Sun was his coverage of the Nevada Parole Board and Supreme Court, where over several decades he covered numerous hearings for some of the state’s most infamous killers, among them Thomas Lee Bean.

Bean was an 18-year-old Wooster High School student when he was convicted of killing 1960 British Olympic team skier Sonja McCaskie in her Reno home on April 5, 1963 — a crime that has been called the most heinous in the state’s history. (She was sexually assaulted, her heart was cut out and stomped on, her head was cut off and her body was found stuffed in a hope chest.)

After the Nevada Supreme Court ordered a new penalty hearing for Bean, the case’s prosecutor, future longtime state Sen. William Raggio told Ryan for a UPI story published in the Sun on Feb. 4, 1970: “This 3-2 decision is an example of judicial legislation at its very worst.

“It is unexplainable and uncalled for. The net effect is to overturn the conviction and penalty seven years after a jury found him guilty and imposed the death penalty. I will have to try this whole case completely over.”

Eventually, Bean’s death sentence was commuted to life without parole and today Bean remains incarcerated in Nevada’s prison system.

In the late 1970s, Ryan was among the first to report on Las Vegas mobster Tony Spilotro drawing the attention of gaming authorities in Carson City and their efforts to put Spilotro’s name into the Black Book of undesirables, banning the gangster from entering Nevada casinos.

In a UPI story published June 26, 1978, in the Sun, Ryan questioned then-Nevada Gaming Commission Chairman Roger Trounday about whether authorities were looking into rumors that the Chicago native was the watchdog for the underworld’s money in Las Vegas casinos. Trounday admitted to Ryan that an investigation into Spilotro indeed was ongoing.

“He (Spilotro) is hanging around Las Vegas and I don’t think it’s for his health,” Ryan quoted Trounday as saying.

The investigation, Ryan reported, included federal agents searching the Gold Rush Ltd. jewelry store in Las Vegas that was operated by Spilotro, his brother John Spilotro and mob associate Herbert “Fat Herbie” Blitzstein. Agents were looking for evidence of, among other things, loan sharking, extortion, and racketeering, Ryan reported.

Spilotro eventually was banned from Nevada casinos and killed by his own mob bosses.

In 1989, Ryan’s coverage of a controversial bill passed by the Nevada Legislature that June, giving lawmakers a 300% raise in their pensions, kept Ryan’s byline on the front page of the Sun and other UPI newspapers for months as he uncovered details about the legislation.

The uproar caused by passage of the bill that was deemed by many to be the epitome of greed by elected public officials ended in repeal during a special session of the Legislature that had been called by then-Gov. Bob Miller specifically for the purpose of repealing that measure.

Subsequent coverage of the issue by Ryan, first as a UPI reporter and later as a Sun employee, had far-reaching impact on state government. Many of the lawmakers who had championed the pension boost became so unpopular with their constituents they either chose not to run for reelection or were defeated in the next election cycle.

Ryan remained with UPI until it underwent worldwide downsizing and closed its Nevada offices in 1990. Because the Sun had long subscribed to the UPI wire service and needed a Northern Nevada-based Capitol Bureau chief, Ryan seamlessly went from his first journalism job to what would be his second and last reporter position that same year.

Matt Hufman, editor of the Sun’s editorial and opinion pages, said Ryan could reach governors for comment on stories quicker than any other reporter he ever worked with.

Hufman said that Cy told him the secret of his success simply was stepping out of his basement office and climbing a nearby staircase that led to the ground-level lot where the governor parked his car. If the car was there, Ryan would quickly reach the governor in his office. “Cy also was known for sitting on the hood of the governor’s car and waiting for the governor to go to his parking space so that Cy could get a comment from him then,” Hufman said.

Ryan married the former Linda Contreras, on Aug. 22, 1972, according to Douglas County marriage records. Mrs. Ryan, whose long career in state government included seven years as Nevada’s welfare director, died in 1999 at age 57 from an aneurism on a flight to Paris.

The Ryans had no children, though Linda had a son from a prior marriage, Sam Contreras, who remembered his stepfather as an athlete who was as dedicated to sports as he was to his job.

“Cy used to put together news media basketball teams to play (charity games) against a team put together by the governor,” Contreras, a resident of Carson City, recalled. “Then he and I would play for the governor’s team against the media team. Cy also was an avid swimmer, softball player, bicyclist, 10K runner and race walker who often won his age group in races.”

Among Ryan’s greatest racing accomplishments were a 10th place finish in the 2005 Silver State Marathon’s 10K event in 1:17:55; a second-place finish in the 2006 Nevada Day Classic 2-Mile Walk in 24:10 and a victory in the 2004 Jester’s Jog 2-Mile Walk in 22:02 — all in Carson City.

In April 2009, Ryan teamed with Carson City Mayor Bob Crowell to compete in the Prison Hill Half-Marathon two-man relay race. They called their team “Libel and Slander.”

Contreras said Ryan was a longtime volunteer UNR basketball statistician and a member of several slow-pitch and fast-pitch softball teams in Carson City.

Services are pending.

Ed Koch is a former longtime Sun reporter. Sun Librarian Rebecca Clifford-Cruz contributed research to this report.