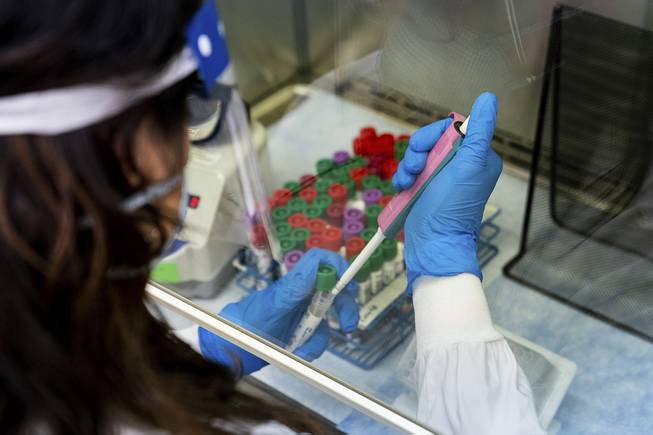

Erin Schaff / The New York Times

A lab technician prepares COVID-19 specimens for testing in April 2020 at a Quest Diagnostics facility in Chantilly, Va. Nevada’s experience with farming out test results to a lab in Chicago when the delta and omicron variants of the coronavirus were breaking out in 2021 uncovered a lapse in the U.S. public health administration: The lack of national standards for ongoing verification of lab results.

Sunday, Sept. 4, 2022 | 2 a.m.

The headline was jarring: “The COVID testing company that missed 96% of cases.”

The story, co-published in May by ProPublica and the Nevada Independent, concerned how jurisdictions throughout Nevada contracted with Chicago-based Northshore Clinical Laboratories starting in the summer of 2021 for testing when the omicron variant of COVID-19 was rampant. Soaring coronavirus cases brought a high demand for fast turnaround with the test results.

“There was a massive need,” said Angelo Palivos, who along with brother Greg subcontracted with Northshore in Nevada to handle specimen collection. “I remember at one point driving past a testing site at (casino) parking lot in Las Vegas and seeing cars wrapped around the corner waiting.”

Northshore’s lab in Chicago would process polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results for thousands of samples collected in Nevada. Some of the results were reportedly flawed. The batch of tests focused on in the story — and the sample that inspired the headline — showed that 49 out of a total of 51 tests were initially reported as negative, only to later be determined as positive.

Almost completely overshadowed by the lurid headline was a deeper story about Nevada uncovering a serious gap in America’s public health administration. Over the many months of the pandemic, little ongoing verification of test results and collection procedures appears to have been done anywhere in the nation.

In Nevada, only those 51 samples — a fraction of 1% of all tests from Nevada processed in Northshore’s Chicago lab — were known to be inaccurate. Such a small number meant a single bad batch might be at fault, or even a few technicians swabbing inaccurately during collection.

Simply put: With a sample of only 51, you can’t draw any conclusions about the thousands of other tests Northshore did. Most could be reliable; most could be unreliable. No one knows.

This is because after initial licensing, no mechanism existed for ongoing random testing protocols to ensure results continued to be accurate.

There are no clear lines of responsibility for scrutinizing collection facilities and labs to ensure results are accurate and administered properly, as health officials wait for someone to file a complaint — as was the case in Nevada with Northshore — before launching an investigation.

In multiple interviews over several weeks, the Sun found a common theme: The scope of the public health crisis created interjurisdictional confusion: city, county, state and federal health officials found themselves not staffed to handle the realities of testing and vaccinating nearly everyone in the nation. In Nevada, as in the nation as a whole, officials had to improvise daily against a rapidly changing virus, waves of sick people and a society that had been largely shut down.

Late last week, Angelo Palivos, who found himself trying to sort out the situation, expressed it this way to the Sun: “Through this experience we identified a national issue which requires better oversight and random test verification from the federal government. More federal oversight over this important health issue will help everyone — the government, testing companies and consumers.”

Northshore comes to Nevada

Razi Khan, the director of partnership at Northshore, contacted the Palivos brothers to gauge their interest in early 2021 to contract with Northshore to offer sample collection services in Nevada, said Angelo Palivos, a Henderson resident. The men have a friendship of 15 years, Pavilos said.

Under this model, which was used elsewhere in the country, local companies collect the samples for PCR tests and then they are sent to Northshore in Chicago to process results.

At this point in the virus timeline, there wasn’t a significant need for testing. Cases were manageable with existing testing capacity, he said. That narrative changed by the summer when the delta variant hit and the omicron variant followed a few months later. The test positivity rate in Reno, for example, soared to 20% in September 2021.

“Omicron was something that we had never seen before in our lives, like the hysteria around it,” Angelo Palivos said, “the unpredictability was just … nobody had seen it.”

The brothers talked with parents in the Reno area whose children were sent home from school after showing signs of an infection and were left in limbo for 10 days while waiting for their COVID PCR test results, Greg Palivos said. It would take four to five days to get an appointment for a test and another three days for a Washoe County-issued result.

“There’s not really any point in testing if you’re going to get a result after seven to 10 days,” Greg Palivos said. “They were severely impacted by the lack of testing options.”

That’s when the brothers, under their company PAL Ventures, became licensed with Nevada to administer the collection of samples to be sent to Northshore.

A former director at the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services with a long-standing reputation in state government vouched for Northshore, the governor’s office said in a statement, and the state’s agency followed the necessary criteria required to approve Northshore’s license for collection and processing of results.

A spokesperson for the Nevada Department of Health and Human Service said Northshore’s licensing process followed the same protocols of other companies seeking a lab license.

Once licensed with the state, Northshore officials in Chicago could negotiate with individual jurisdictions — the city of Las Vegas or Washoe County School District, for instance — to begin testing. The state only gave the license and wasn’t involved in dealing with jurisdictions, the spokesperson said.

At the time the state licensed Northshore, the facility claimed on its website that it was conducting testing in 42 states. Nevada at the time was in a declared health emergency, where “the scale of the public health crisis brought testing mandates (required to return to work or play in a sporting event), but there was nobody to ensure proper testing was available,” Angelo Palivos said

The Palivos brothers hired and trained staff to swab residents at collection sites then sent those specimens by overnight delivery to Northshore’s lab in Chicago for PCR analysis, Angelo Palivos said. There was such a need that they went from a crew of 30 contracted collectors to 150, as “we were hiring as fast as we can and training as fast as we can to keep up with the demand,” he said.

In the Reno area, they provided testing for the Washoe County School District and UNR in late 2021 as the omicron variant surged, and Angelo Palivos said he was in constant communication with leadership of both entities as they managed the high need for testing.

The Palivos collection sites performed rapid antigen tests processed on site, and sample collections for PCR tests that were sent to Northshore in Chicago. Nearly every patient was swabbed twice each visit — once for the rapid and then for the PCR.

'Thousands of weekly tests'

Angelo Palivos said one hiccup encountered came from the Washoe school system in regards to conflicting antigen results for high school athletes, who were tested weekly and needed a negative result to be able to compete. Nevada was one of a few states to cancel a majority of prep sports in the 2020-21 academic year, meaning the fall 2021 season carried extra significance. Many families expressed concerns about testing teenagers who showed no symptoms of the virus.

In some athletes, the rapid antigen result produced at the collection site differed from the PCR lab result later given, Angelo Palivos said. Swabbing the nose for a rapid test was not reliably detecting the omicron variant in the initial few days the virus was in someone’s system, health experts said.

A study in July from Cochrane, a global health research group, found that rapid tests correctly identified COVID-19 in 73% of people with symptoms and 55% without symptoms. In other words, antigen tests were delivering false negatives between 27% and 45% of the time.

Angelo Palivos said that, like the national studies, they also saw antigen tests deliver negative results for omicron while the Northshore PCR tests for the same patient came back positive.

The chances for discrepancy were enhanced because “we were doing thousands of weekly tests on athletes,” Angelo Palivos said.

However, families of athletes also expressed concerns about the PCR tests coming back from Northshore when a group of them came back as “inconclusive” when the district desired a positive or negative result to determine whether a student could return to activities, he said.

“This casts more doubt on the efficacy of Northshore lab, in what is already a very fragile situation with plenty of doubt cast,” Angelo Palivos wrote in a Dec. 16, 2021, email sent to Northshore, shared with the Sun. “This is very concerning to everyone in Washoe County, and us as well. We are going to do 12,000 specimens this month for the school district alone but they have indicated that they are losing faith in our lab’s process, and sending inconclusive results certainly doesn’t help that.”

Around the same time, Dr. Cheryl Hug-English, director of the UNR student health center, also noticed conflicting results with tests given to students and staff. She expressed her concerns to Palivos, and they agreed to take a third sample on the next batch of tests administered with Palivos paying for the labor, he said.

Those 51 PCR samples collected from UNR students and staff were retested by Nevada State Public Health Lab, which found a false negative rate of 96.1%, according to an email from Andrew Gorzalski, a molecular supervisor at the lab.

Gorzalski said in the email that the issue could be due to improper shipping and storage conditions, the extraction process, improper real-time instrument calibration or primer binding issues during PCR. He also speculated that the Northshore lab in Chicago might not be running the collected samples correctly.

More importantly, it highlighted the chaos in regulatory control over the testing process as the world was navigating the health crisis brought on by the pandemic.

The 96% failure rate would eventually make its way into a shrill headline, but it was profoundly misleading. Beyond that sample of 51, there was no system in place, apparently anywhere in America, to randomly confirm the results in tens of thousands of other tests.

It’s worth noting the Palivos collection facilities administered thousands of both rapid antigen tests and PCR tests on the same patients. Those results were broadly in line with national findings that PCR tests — in this case processed by Northshore — identified more positives than antigen tests.

That detail flies in the face of the notion that Northshore’s PCR tests were delivering false negatives on a massive scale. However, comparing antigen results to PCR results simply isn’t the same as randomized ongoing confirmation of results by qualified health officials.

The uncertainty is compounded by Northshore’s behavior when the accuracy issues were raised: rather than working with officials to sort the matter out, the company simply suspended testing and stopped working in Nevada.

Federal pressures

The Northshore incident wasn’t the only time COVID testing results were an issue in Nevada. Nor was it the only time the question of who is ultimately responsible that tests are administered and processed correctly was raised.

In October 2020, the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services ordered long-term care facilities to stop using two COVID-19 antigen tests that had been supplied by the federal government. The reason: The brands of the test, which could deliver results in about 15 minutes, had an unusually high number of false positives.

In a directive, the state wrote that “possible reasons for conflicting test results include lack of compliance with the manufacturer’s protocols; inadequate training on the testing procedure.”

As millions of Americans who have now self-tested for COVID know, the swabbing process all by itself can invite errors.

The letter continued by referencing a Nevada statute that requires skilled nursing home facilities to maintain a program to control infections and ensure the safety of staff and residents. The letter was written by Melissa Peek-Bullock, the state epidemiologist in the Office of Public Health Investigations and Epidemiology.

Further, the state said it would continue testing as mandated by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, just not the suggested antigen tests from Quidel and Becton, Dickinson and Company supplied by the federal government.

At the time, fast results were important because, nationally, the vulnerable populations at nursing homes had high infection rates.

Nevada’s decision didn’t sit well with the federal government, which characterized the decision as “only be based on a lack of knowledge or bias,” Dr. Brett Giroir, assistant secretary for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, wrote in a letter to Nevada Department of Health and Human Services.

He continued, “There is no scientific reason to not comply with this.”

The letter detailed how Nevada’s ban was a violation of federal law preempting a state or local to prohibit the use of the tests. In essence, the federal government was pressuring Nevada to ignore its concerns about the tests.

Lab licensing and oversight

To perform any lab specimen collection or laboratory testing in Nevada, potential licensees must submit an online application — for both a Nevada laboratory license and federal Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certificate — that includes the name of a qualified laboratory director, said Shannon Litz, public information officer for the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services.

Once the information is reviewed, it is included in both a Nevada database and a federal database, and a state surveyor comes to inspect the facility, Litz said.

If any issues are found, they need to be corrected and a plan of correction is submitted. When the application has been approved, the laboratory may begin performing specimen collection and laboratory testing, Litz said.

Inspectors make sure the collection is administered according to the manufacturer’s instructions, the collection personnel have documented evidence of training history on how to collect specimens and perform the tests and that safety protocols are in place, Litz said.

Facilities that only collect specimens to send to a laboratory for analysis do not require a federal certificate since they are not performing any on-site testing, said Cody Phinney, deputy administrator for Nevada’s Division of Public and Behavioral Health.

“Nevada does have regulations that are state specific, that some states don’t have,” Phinney said. “Some states just use the federal regulations. And in this case, that did allow us to have a more substantial statement of deficiencies.”

The Illinois attorney general’s office received more than 40 complaints about Northshore, mostly because of the delays in response time for results, according to Block Club Chicago, a nonprofit news organization covering Chicago’s diverse neighborhoods. Additionally, the Better Business Bureau received 13 complaints and gave the company an “F” rating.

Northshore’s Chicago lab simply didn’t have the capacity to handle the mass quantity of samples it was getting from many states, Angelo Palivos said.

Once he saw the Chicago lab having difficulties, he pushed them to fix the problem, according to an email exchange. A week later in mid-January, the UNR informed Angelo Palivos of the inaccurate tests in a batch of 51 samples and he instructed his collectors to stop administering the PCR tests that would be shipped to Chicago for processing, he said.

Northshore has been investigated by multiple state agencies in Illinois and cited by federal regulators — but only after those groups were informed of the problems. Yet, Northshore remains in operation.

Americans are accustomed to the notion that regulators are out there ensuring product, food and drug safety. There are ongoing field tests of restaurants, food and drugs to ensure their safety is monitored on a regular basis. The same exists in safety testing for many products such as automobiles.

Regulation isn’t so cut and dry with labs.

A federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) spokesperson said in an email that the CMS’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments program provided resources to laboratories that performed testing on patient specimens to “ensure accurate, reliable, and timely results.”

When noncompliance is found on a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments survey, the laboratory is given an opportunity to respond and correct the cited deficiencies.

If the laboratory fails to become compliant, CMS proposes sanctions, then the lab is given an opportunity to submit evidence or information as to why sanctions should not be imposed. CMS then makes the enforcement decision about imposing sanctions.

Northshore submitted an allegation of compliance on Jan. 24, 2022, however CMS determined that the laboratory’s submission did not constitute a credible allegation of compliance and acceptable evidence of correction, so the CMS proposed sanctions on the laboratory.

The laboratory submitted a second allegation of compliance on April 6, which is currently under review.

“We continue to review our investigative findings to determine appropriate actions under our authorities,” the CMS spokesperson said.

Northshore is under investigation by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of Inspector General, which has had a case open for “quite some time,” according to a May 17 email from Peter Theiler, a special agent in Chicago, that was obtained by the Sun.

Nevada’s inspectors and inspections

Nevada employs six inspectors to oversee slightly less than 2,000 licensed labs and the 16,000 technicians at those facilities, Phinney said.

Once a facility passes the initial requirements to get up and running, an inspector can randomly make visits to ensure they are following protocols. However, Phinney said, there’s no set standard on when an inspector checks — some labs in good standing may go more than one year without seeing anyone.

Rather, the state waits for inbound alerts and then deploys an inspector. And those inspectors examine lab sites, facilities and processes; they don’t have the ability to randomly confirm test results.

“We’re really dependent on hearing from customers of labs, other health care providers, if they perceive that there’s a problem,” Phinney said. “We really need those complaints, because we do go check on all complaints that are about that kind of quality.”

Phinney said the state received one complaint about Northshore and visited the collection company’s facility in Henderson. Nevada requires collection groups such as the one operated by the Palivos brothers to be associated with a lab, even though tests its collectors administered were sent to the Northshore lab in Illinois for analysis.

The inspector found Jan. 18 that the director of the facility failed to make sure the collection was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and that they failed to document the room temperature consistent with the manufacturer’s acceptable storage requirements, according to the summary Statement of Deficiencies obtained by the Sun.

The inspector further found that nasal swabs used to collect patient samples were observed intermingled in a carrier outside of the individual test kits, and there was no policy or procedure for the collection and transport of COVID-19 specimens for PCR testing to the main lab in Illinois.

But in a Feb. 2 letter from the state to the lab, the inspector wrote “the allegation of reporting discrepant results was unsubstantiated due to the lack of sufficient evidence.”

The state also found they were collecting PCR samples at a Washoe County location where they were only licensed antigen tests. Angelo Palivos said he was unaware of this licensing issue with Northshore, explaining that as a subcontractor he would set up facilities where directed by Northshore, which handled licensing.

“Some states just use the federal regulations. And in this case, that did allow us to have a more substantial statement of deficiencies,” Phinney said. “So that gives me comfort that we do have some of those state-specific requirements that we can lean on.”

The state gave two weeks for local facilities to correct seven issues in the Statement of Deficiencies. The plan of correction submitted two weeks later was denied.

On Feb. 23, Northshore notified the state it was suspending all testing in Nevada, according to a document provided to the Sun. By March 2, the state received notice from Northshore that it was voluntarily closing its lab license.

Ultimately, it’s the responsibility of leadership at each lab to ensure test results are processed correctly to produce an accurate result, Phinney said. “Our regulations require the (facility) director to be responsible (for accurate tests). ... Our job is to enforce those rules.”

She stressed that the state wanted to maintain the public’s trust in health care, which is whythe Division of Public and Behavioral Health sprung into action after receiving the complaint.

“We certainly don’t want to do anything where people don’t access screening, testing and immunization,” she said.

Testing becomes political

A website launched late last month connected to Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo’s GOP gubernatorial campaign cites the Northshore incident as one of the reasons to not reelect Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak.

The website appears determined to make this a campaign issue by focusing on the lurid headline and not the underlying facts. It even suggests people died as a result but providing no underlying evidence.

The site states that “Steve Sisolak’s tenure as governor has been riddled with corruption, including fast-tracking a $165 million no bid contract to a company connected to a major Sisolak campaign donor to provide COVID testing kits that had an inaccuracy rate of 96%. Nevadans died.”

What it fails to mention is the 96% inaccuracy rate was from one batch of 51 samples, and not the estimated 70,000 of other tests the Palivoses said were performed. Those results could be reliable or unreliable — nobody knows because of the systemic lack of ongoing random tests to confirm results.

Additionally, the state’s involvement was giving a Nevada laboratory license and federal certificate to Northshore, which then negotiated with counties and other jurisdictions. The state had nothing to do with facilitating the agreements, and the Washoe County School District was unsatisfied with a previous company before switching to Northshore to test its athletes, Angelo Palivos said.

Sisolak does have a relationship with Peter Palivos, a Las Vegas philanthropist and investment manager who is the father of Angelo and Greg and has contributed at least $25,000 to Sisolak’s campaigns over the last five years, according campaign finance disclosures.

Sisolak’s office said in a statement when the story was released that Sisolak didn’t have any conversations with Peter Palivos about Northshore or its operations. Peter Palivos’ sons stress their father wasn’t involved in launching their test sample collecting endeavor.

Sisolak also said Northshore’s “negligence is despicable.”

“The governor was never involved in expediting Northshore’s licensing process and he never directed his staff to expedite their licensing,” the statement said. “Neither the governor nor his staff were involved in any way in Northshore’s independent contracts with local entities.”

But in an election year, a provocative headline will become political fodder. Lombardo and his allies seem determined to weaponize one part of the facts — those 51 known bad tests out of tens of thousands administered — while ignoring the full context. Lombardo is getting help from the Republican Governors Association, which is pumping $2.5 million into a statewide campaign to highlight the testing inaccuracy, according to the Nevada Independent. Those ads are suggesting lives were lost — something that’s unfounded.

That includes a Twitter post Wednesday sharing the ad that is critical of Sisolak for “fast-tracking shady contracts for a COVID testing company at the request of his campaign donor. The only problem? The company got 96% of their results WRONG. Sisolak will pay for his corruption in November.”

Lombardo used a hashtag #NorthshoreSteve when retweeting the post, writing “Steve Sisolak must be held accountable for his corruption and cronyism.”

While campaigns often overstate matters or misrepresent facts, asserting that 96% of all of Northshore’s results were wrong is untrue, particularly when the sample size was so small. At the moment, all that can be stated for certain is that less than 1% of all the Northshore tests are known to be wrong.

That highlights the starker reality and an issue public health officials recognize: There is no system in place to validate results after initial licensing.

Going forward

With Northshore no longer doing business here, the logical next step is adding mechanisms for ongoing randomized verification of tests to ensure results are accurate.

The best way, officials say, might be following a similar game plan as when dealing with Northshore.

Sisolak said in an interview with the Sun that the situation was unfortunate but the process worked.

“With labs though, can there always be more oversight? Sure,” Sisolak said. “But the system, we always have people, when you’ve got the government instituting a program and giving out contracts and money, some people are going to take shortcuts, sadly.”

He continued, “The state process, as it was in place, worked. They got a license, it was approved by CLIA, the federal government. They got contracts with these different jurisdictions, they never had a contract with the state.”

Nevada only requires state licensing for laboratories that are located outside Nevada when they are performing workplace drug testing.

Asked if he would want to change that regulation so other labs require a license, Sisolak indicated that he did not know how that would be done because there are many labs across the country. For instance, some resorts were using a lab in California, meaning Nevada would be relying on another state to hold a lab accountable.

“I would think that the federal government would have a … plan in place to make sure that labs or the states are all following up on this,” Sisolak said.

Sisolak wants to build more capacity in Nevada with its own health labs to absorb a lot of the testing so, in the future, it can rely less on labs like Northshore. He said the state health lab was small “and that’s something we’ve been working with both universities about expanding the health labs.”

“This was a situation that was unfortunate,” Sisolak said. “I mean, how it came about, I think that you’ve got somebody that took some shortcuts there. But I talked to other people who had no problems. So I don’t know how bad the testing was, overall.”

“I think the best thing that we can do is to increase the capacity in the state at the two universities where we have, you know, health districts in our health lab up here in the north,” Sisolak said.

Asked what needs to be fixed going forward, Angelo Palivos said, “There needs to be more information between federal and state oversight. That goes to the state vs. federal argument from the dawn of America.”

Multiple Sun staffers contributed to this story. Contact managing editor Ray Brewer at 702-990-2662 or [email protected].