Thursday, Dec. 4, 2008 | 2 a.m.

From developing photovoltaic cells to interviewing witnesses of atomic blasts at the Nevada Test Site, graduate students play a key role in research at UNLV.

Master’s and doctoral candidates teach, toil in the lab and collect data in the field. To build a top-of-the-line research institution, the university needs to lure some of the best.

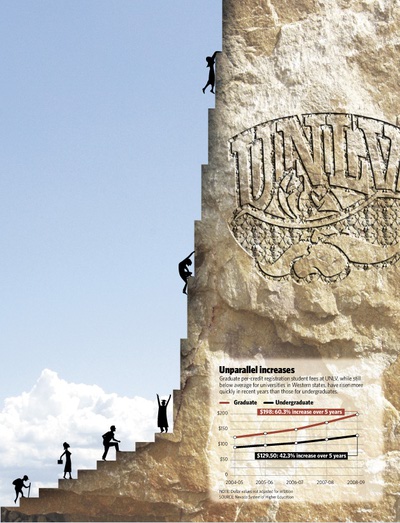

It doesn’t help that UNLV’s graduate students could be looking at a fifth consecutive year of double-digit fee increases.

For Nevada residents, graduate registration fees rose by 15 percent this year and last and by 10 percent in the 2006-07 and 2005-06 academic years — faster than the pace at which undergraduate fees have risen.

With colleges facing severe budget cuts, a 25 percent fee increase for all students is possible next fall, says Jim Rogers, chancellor of Nevada’s public higher education system. Such a hike would raise an estimated $46 million in new money in the 2009-10 fiscal year.

Last week, news reports and statements by higher education officials indicating that the 25 percent increase could come as early as the spring semester triggered widespread anxiety among students.

But Rogers and Michael Wixom, chairman of the public college system’s Board of Regents, now say that won’t happen.

Still, Rogers says that in dire financial times, everyone needs to chip in. “We understand students are the least able to participate, but we think that they ought to participate to some extent,” he says.

Wixom says regents will consider each group of students’ needs before deciding how much to charge them.

Graduate students already pay more than undergraduates, and Rogers says that’s fair in part because workers with graduate degrees typically land better-paying jobs than those with only bachelor’s or associate degrees.

Graduate programs are also more expensive to run, with smaller class sizes and high-priced research equipment.

Carl Reiber, associate dean of UNLV’s college of sciences, says that while rising costs might not drive off current master’s or doctoral candidates, continued fee increases could damage UNLV’s ability to court the best emerging talent.

Graduate students have seen their costs rise from $123.50 per semester credit in 2004-05 to $198 per semester credit today.

Jessica Lucero, president of UNLV’s graduate and professional student association, says the fact that undergraduates have seen fees grow more slowly “kind of digs at our sides a little bit, like a thorn.”

One reason for the disparity in the rate of increase: UNLV’s graduate fees are further below the median for Western colleges than its undergraduate fees are, says Dan Klaich, executive vice chancellor of Nevada’s public higher education system. That’s based on fees at public schools in 15 states that make up the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education.

Lucero says while graduate students are willing to discuss fee increases, 25 percent “is too much.”

“We keep hearing from the administration that we’re supposed to be a research institution, we’re on our way, and we fully support that mission,” Lucero says.

“Graduate students are the ones that are going to drive that research,” she says. “They’re the ones that are going to mentor the undergraduates. They’re the one that are going to be doing the experiments. They’re the ones that are going to be carrying out these large-scale projects.”

In that context, Lucero says, the administration needs to do more to help master’s and doctoral candidates financially.

She noted that over the years, the state-funded stipends that graduate students receive for teaching and researching have remained stagnant. They typically amount to $10,000 for nine months of work for master’s students and $12,000 for Ph.D. candidates.

Other colleges offer better deals. At Arizona State University, history research assistants draw an average of $13,400 per academic year and economics teaching assistants $17,586, according to a Chronicle of Higher Education survey. The University of California at San Diego pays teaching assistants in various departments an average of $16,391 per school year.

This fiscal year, UNLV expects to spend about

$9.9 million supporting about 750 state-funded graduate assistants.

Because the school pays nearly 70 percent of their registration fees, the number of graduate assistants the university can afford to fund falls each time fees go up, says Gerry Bomotti, senior vice president for finance and business.

Raising graduate assistant stipends was the top priority that emerged from a series of town hall meetings UNLV administrators held in 2007-08 to discuss the direction the university should take in coming years.

UNLV President David Ashley acknowledges, however, that finding new money to pay for stipends will be difficult given the state’s dismal budget projections.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy