John Stephens II, along with son John III, has a souvenir sticker after voting last week at Pearson Community Center in North Las Vegas. The elder Stephens speaks proudly of his great-great-great aunt, Mollie Corney, who braved prejudice to vote long before poll taxes were outlawed.

Thursday, Oct. 30, 2008 | 2 a.m.

Sun Topics

Sun Archives

- State: No false or stifled votes here (10-29-2008)

- We’re American citizens and we vote (10-29-2008)

- Democrats continue to stream into early voting polls (10-28-2008)

John Stephens II, who is black, cast his vote last week with a sense of purpose, history and pride, clutching a pink piece of paper that shows how far the nation has come.

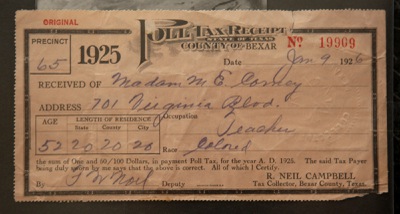

It was weathered and wrinkled, so tissue-thin that he keeps it in a leather folder tucked inside a satchel. It goes back to 1926, when Stephens’ great-great-great aunt was forced to pay a $1.50 poll tax for the right to vote. It’s the equivalent of about $18 in today’s world.

This was her receipt.

And if only Madam Mollie E. Corney, who died in 1930, could know that today there is not only no poll tax but people are voting for a black man for president.

“If it wasn’t for people like her, we wouldn’t be here,” he said. “Here we are making the connection 82 years later.”

Next to Corney’s poll tax receipt in the folder is his own poll tax receipt from 1964, from the same place, Bexar County, Texas. Later that year, the 24th Amendment outlawed poll taxes — used to alienate poor and minority voters — as conditions for voting in federal elections.

Texas continued to fight for the taxes until a Supreme Court ruling two years later.

Stephens, a retired appliance repairman, has told the story of his auntie hundreds of times. He’s told his sons, John Stephens III, 42, and Brandon Stephens, 27.

The sons will pass the story to future generations.

John Stephens III, a library assistant, wondered whether he would have paid the tax. It seems so corrupt, he said, that it would have been easy to just forget about taking part in the process. “She (Corney) saw it as a matter of principle,” the son said.

In the early 1990s, the family set up an exhibit, featuring photos of Corney and displaying the poll tax receipt, at the West Las Vegas Library. Presentations were made to dignitaries.

Stephens runs local exhibits as the head of Black Extravaganza, an organization that brings attention to the battle for civil rights. Its displays have highlighted the history of West Las Vegas, the cultural contributions of black artists and the role of black performers in early Las Vegas.

Last week, as he prepared to vote, the elder Stephens gazed at a photo of his auntie, reflecting on her role as a voter who would not be intimidated.

“She went down there to the tax assessor’s office full of white folks,” Stephens said. “It wasn’t a pleasant place to be. She was walking among people who thought she didn’t have the right to be part of the political process and who were biased against her in the first place.”

With that, Stephens walked up to the computer screen and voted.

Join the Discussion:

Check this out for a full explanation of our conversion to the LiveFyre commenting system and instructions on how to sign up for an account.

Full comments policy